Brief Overview

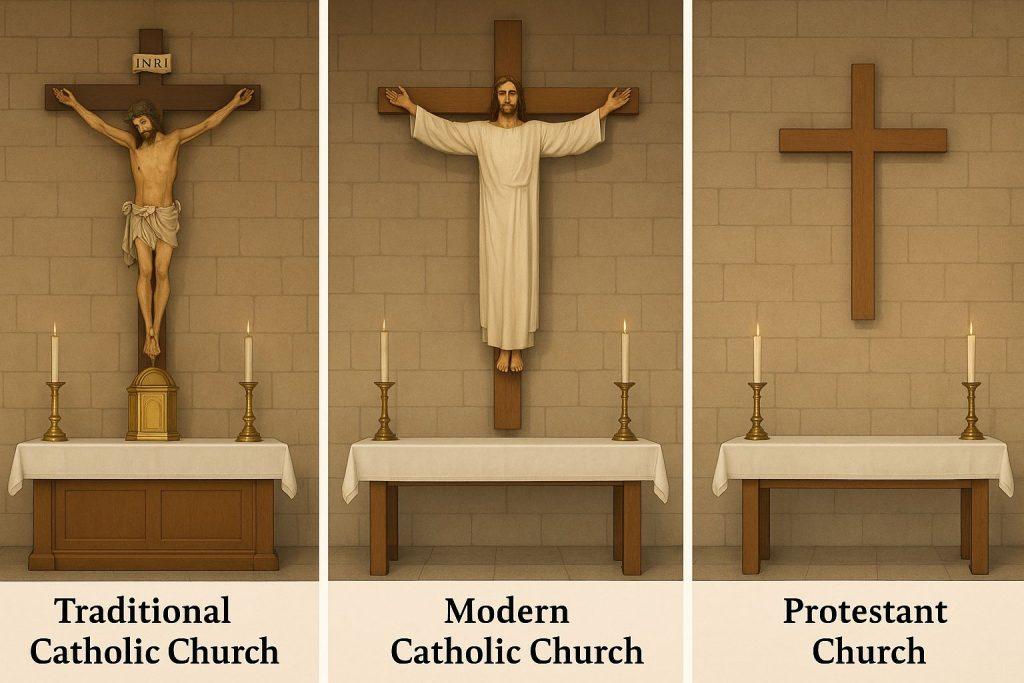

- Catholics prominently display the crucifix, emphasizing Christ’s suffering as central to salvation.

- Protestants typically use a bare cross, symbolizing Christ’s resurrection and victory over death.

- The Catholic theology of suffering invites believers to unite their trials with Christ’s Passion.

- Protestant theology, rooted in sola fide, often views suffering as a past event, not a participatory act.

- Modern Catholic churches sometimes adopt a “resurrected Christ” on the cross, diverging from tradition.

- The crucifix serves as a reminder of the cost of salvation and the believer’s call to carry their cross.

Video Response

Detailed Response

Catholic Emphasis on the Crucifix

The crucifix, depicting Christ’s wounded and suffering body, is a cornerstone of Catholic worship spaces. It is not merely a decorative piece but a profound theological statement. The image of Christ crucified reminds Catholics of the immense sacrifice made for humanity’s redemption. This visual representation aligns with the Church’s teaching that salvation is inseparable from the cross (CCC 618). The crucifix invites believers to reflect on their own participation in Christ’s suffering. It underscores the reality that following Christ involves embracing personal trials. In Matthew 16:24, Jesus explicitly calls disciples to take up their cross. The crucifix, therefore, serves as a constant reminder of this call to self-denial. Catholic churches, especially those built before the 20th century, place the crucifix prominently above the altar. This placement ensures that the faithful are oriented toward the sacrifice of Calvary during worship.

The Catholic understanding of suffering is deeply participatory. Believers are called to offer their struggles—whether physical, emotional, or spiritual—in union with Christ’s Passion. This theology is rooted in Colossians 1:24, where Paul speaks of completing what is lacking in Christ. Wood, a Catholic theologian, explains that suffering, when united with Christ, becomes redemptive. The crucifix visually reinforces this teaching, showing Christ’s agony as an invitation to share in His redemptive work. Practices like fasting, penance, and the Stations of the Cross are practical ways Catholics live out this theology. These acts are not seen as earning salvation but as cooperating with God’s grace. The crucifix, therefore, is a call to action, not just a symbol of a historical event. It challenges Catholics to see suffering as a path to holiness.

Protestant Preference for the Bare Cross

Protestant churches often display a bare cross, symbolizing Christ’s resurrection and triumph over death. This choice reflects a theological emphasis on sola fide—salvation by faith alone—where Christ’s work on the cross is seen as complete and sufficient (CCC 1996). For many Protestants, the crucifix, with its focus on Christ’s suffering, may seem unnecessary or even morbid. The bare cross emphasizes that Christ is no longer on the cross, highlighting the victory of Easter Sunday. This perspective is particularly evident in evangelical and Reformed traditions. Theologians like John Calvin argued that excessive focus on Christ’s suffering could distract from His glorification. As a result, Protestant worship spaces often avoid images that dwell on the Passion. The bare cross, therefore, becomes a symbol of hope and assurance.

This emphasis on victory shapes Protestant attitudes toward suffering. Unlike Catholic theology, which sees suffering as participatory, many Protestant traditions view it as a consequence of sin or a test of faith. The concept of “offering up” suffering for spiritual growth is largely absent. Instead, suffering is often something to overcome through faith or divine intervention. For example, in some evangelical communities, illness or hardship is interpreted as a lack of faith. This perspective contrasts sharply with the Catholic view of suffering as a share in Christ’s redemptive mission. The bare cross, while affirming Christ’s victory, does not visually convey the cost of that victory. As a result, Protestant theology often prioritizes assurance of salvation over endurance through trials. This difference is evident in worship practices, which focus on praise and preaching rather than sacrificial themes.

Theological Implications of the Bare Cross

The absence of the crucifix in Protestant churches reveals a broader theological divergence on the nature of Christian life. Catholic theology, as articulated in Romans 8:17, teaches that believers are co-heirs with Christ if they suffer with Him. The crucifix serves as a constant reminder of this participatory suffering. In contrast, Protestant theology often emphasizes the sufficiency of Christ’s sacrifice, reducing the role of human suffering in salvation. This can lead to a Christianity focused on personal assurance rather than transformation through trials. The bare cross, while affirming resurrection, risks sidelining the reality of ongoing sacrifice. For Protestants, the cross is primarily a historical event, not a present invitation to suffer with Christ. This perspective can make suffering seem like an obstacle rather than a means of grace.

The lack of a theology of suffering in many Protestant traditions has cultural implications. In Protestant-majority societies, particularly in the United States, there is often a focus on prosperity and comfort. The “prosperity gospel,” popular in some evangelical circles, teaches that faith leads to health and wealth. This contrasts with the Catholic view that suffering is integral to spiritual growth. The bare cross, while a powerful symbol of victory, does not challenge believers to embrace their own crosses. As a result, Protestant communities may struggle to find meaning in suffering. The absence of practices like penance or mortification further reinforces this gap. The Catholic crucifix, by contrast, calls believers to a life of discipline and sacrifice.

Modern Catholic Trends and the Resurrected Christ

In recent decades, some Catholic churches have adopted a “resurrected Christ” image on the cross, depicting a glorified Christ rather than a suffering one. This trend, often called a “resurrefix,” is a significant departure from Catholic tradition. Pope Pius XII, in his 1947 encyclical Mediator Dei (section 62), explicitly condemned such images, stating that they obscure the reality of Christ’s suffering. The resurrefix risks confusing the theology of the cross by blending Good Friday with Easter Sunday. Christ did not rise on the cross; He died on it. This innovation reflects a broader cultural discomfort with suffering, even within Catholicism. Some modern Catholics, influenced by secular or Protestant ideas, prefer images that emphasize triumph over sacrifice. This shift can dilute the Church’s teaching on the necessity of the cross.

The resurrefix also raises questions about liturgical coherence. The crucifix is meant to orient worshipers toward the sacrifice of the Mass, which re-presents Christ’s Passion (CCC 1366). A resurrected Christ on the cross undermines this connection, suggesting that the Passion is less central. This trend is particularly troubling in light of Catholic tradition, which has consistently emphasized the crucifix as a focal point of worship. Theologians like Joseph Ratzinger have warned against innovations that weaken the Church’s witness to the cross. The resurrefix, while visually appealing, risks emptying the cross of its transformative power. It reflects a temptation to avoid the discomfort of suffering, both Christ’s and the believer’s. Catholic churches that adopt this image may inadvertently align with Protestant sensibilities, prioritizing victory over sacrifice.

The Cross as a Way of Life

The crucifix is not just a symbol; it is a call to live the cross daily. In Luke 9:23, Jesus instructs His followers to take up their cross and follow Him. For Catholics, this means embracing self-denial, suffering, and service. Self-denial involves prioritizing God’s will over personal desires, even when it is difficult. Suffering with purpose means accepting trials as opportunities for spiritual growth. Dying to sin requires rejecting vices like pride or greed. Living for others entails acts of love, such as forgiving enemies or serving the poor. These practices are rooted in the Catholic understanding of the cross as a share in Christ’s redemptive mission. The crucifix visually reinforces this call, reminding believers of the cost of discipleship.

Historically, Catholics were taught to carry their cross through specific practices. Before the 1960s, the phrase “offer it up” was common, encouraging believers to unite their sufferings with Christ’s for the salvation of souls. Friday penance, including abstaining from meat, was a communal way of embracing the cross. The Stations of the Cross, practiced widely during Lent, helped the faithful meditate on Christ’s Passion. Voluntary mortifications, such as fasting or small acts of self-denial, were seen as ways to grow in virtue. Catholics also accepted illness and death with a supernatural outlook, viewing them as participation in Christ’s suffering. Religious vocations, with their vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, were another way of living the cross. These practices, grounded in the crucifix, shaped a robust Catholic spirituality.

Historical Catholic Practices of Carrying the Cross

Prior to the 1960s, Catholics were deeply formed in a theology of suffering. The daily offering of suffering was a hallmark of Catholic life. Believers were taught to dedicate their struggles—whether illness, poverty, or insults—to God. This practice was seen as a way to cooperate with Christ’s redemptive work (CCC 1505). The phrase “offer it up” was a practical reminder of this teaching, passed down by families and clergy. It reflected a worldview that saw suffering as meaningful, not random. Catholics were encouraged to see their trials as a way to grow in holiness. This approach was supported by devotions like the Morning Offering, which consecrated the day’s struggles to God. The crucifix, present in homes and churches, was a constant reminder of this call. It helped Catholics internalize the connection between their suffering and Christ’s.

Friday penance was another key practice. Catholics abstained from meat every Friday, not just during Lent, as a way of sharing in Christ’s sacrifice. This discipline was communal, uniting the faithful in a shared act of self-denial. Fasting during Lent and other penitential seasons was also widespread. These practices were not seen as optional but as essential to Christian life. The crucifix, often displayed during these times, reinforced their purpose. Catholics understood that penance was a way to imitate Christ’s suffering. This theology was further deepened by devotions like the Stations of the Cross. By meditating on Christ’s Passion, believers learned to see their own trials in light of His. These practices created a culture of resilience and sacrifice, rooted in the crucifix.

Catholic Devotions and Mortification

The Stations of the Cross were a central devotion in pre-1960s Catholicism. This practice, often led in parishes during Lent, invited the faithful to walk with Christ through His Passion. Each station, depicted in images or statues, focused on a moment of Christ’s suffering. Catholics were encouraged to offer their own struggles in union with His. This devotion was not only personal but communal, fostering a shared commitment to the cross. The crucifix, often placed at the center of the stations, was a focal point for meditation. It reminded believers that their suffering had a purpose. The Stations of the Cross were particularly powerful for teaching children and converts the value of sacrifice. They remain a vital part of Catholic spirituality today, though less emphasized in some modern parishes.

Mortification, both voluntary and involuntary, was another way Catholics carried their cross. Saints like Francis of Assisi and Thérèse of Lisieux practiced small acts of self-denial, such as giving up comforts or enduring hardships patiently. Laypeople followed suit, taking cold showers or forgoing pleasures as a way to grow in virtue. These acts were not rooted in self-hatred but in love for Christ. The crucifix inspired such practices, showing that suffering could be transformative. Catholics also accepted involuntary suffering, like illness, with a supernatural outlook. The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick reinforced this perspective, uniting the sick with Christ’s Passion (CCC 1521). Before modern medicine, death was often seen as a final act of carrying the cross. The crucifix, present in sickrooms, provided comfort and purpose in these moments.

Catholic Witness Through Persecution

Persecution and martyrdom were stark examples of carrying the cross. In the 20th century, Catholics in Mexico during the Cristero War (1926–1929) faced brutal persecution for their faith. Many died rather than renounce the Church, seeing their suffering as a share in Christ’s Passion. Similarly, during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), thousands of Catholics were martyred for their beliefs. In Nazi Europe, figures like Maximilian Kolbe gave their lives in acts of heroic sacrifice. These examples were not distant history but living witnesses to the theology of the cross. The crucifix, often carried by martyrs, symbolized their commitment. Catholics were taught that persecution was a privilege, not a punishment (Philippians 1:29). This perspective was reinforced by the Church’s veneration of martyrs. The crucifix remains a powerful symbol of their legacy.

Religious vocations also embodied the cross. Priests, monks, and nuns vowed poverty, chastity, and obedience, sacrificing personal desires for the sake of God and others. These vows were seen as a radical way of imitating Christ’s self-emptying (Philippians 2:7). Religious communities, like the Carmelites or Jesuits, were visible signs of the cross in action. Their lives of service and prayer inspired the laity to embrace sacrifice. The crucifix was a constant presence in monasteries and convents, guiding their spirituality. Before the 1960s, vocations were abundant, reflecting a culture that valued the cross. This witness shaped Catholic identity, emphasizing that holiness requires sacrifice. The decline of religious vocations in some regions today reflects a broader cultural shift away from this theology.

Protestant Life Without a Theology of Suffering

Protestant theology, particularly in traditions emphasizing sola fide, often lacks a robust theology of suffering. Salvation is seen as a gift received through faith, not a process involving participatory suffering. The concept of “offering up” struggles for redemption is foreign to most Protestant communities. Instead, suffering is often viewed as something to overcome or avoid. In evangelical circles, hardship may be interpreted as a sign of weak faith. This contrasts with the Catholic view that suffering can sanctify (1 Peter 4:1). The bare cross, while affirming Christ’s victory, does not invite believers to share in His suffering. As a result, Protestant spirituality tends to focus on assurance and blessing. Practices like penance or mortification are rare. This theological gap shapes a different approach to Christian life.

The absence of sacramental confession further widens this divide. In Catholicism, confession includes penance, which unites the penitent with Christ’s suffering (CCC 1460). Protestants, lacking this sacrament, have no formal structure for redemptive suffering. Repentance is often internal, without acts of discipline or reparation. This can lead to a less tangible connection to the cross. For example, in Protestant communities, fasting or kneeling in contrition is uncommon. The bare cross, while a reminder of Christ’s work, does not call for ongoing sacrifice. This difference is evident in worship, which emphasizes praise over penitential themes. Catholic worship, centered on the Mass and crucifix, keeps suffering at the forefront. The Protestant approach, while valid in its context, offers fewer tools for finding meaning in trials.

Protestant Rejection of Monasticism

The Protestant Reformation rejected monasticism, dissolving monasteries and religious orders. Reformers like Martin Luther viewed such institutions as unnecessary for salvation. This decision eliminated a key witness to the cross through lives of poverty, chastity, and obedience. In Catholic tradition, religious orders embody the evangelical counsels, showing that the cross is a lifelong commitment (CCC 915). Their absence in Protestantism leaves a void in visible sacrifice. For example, in England and Scandinavia, monasteries were closed during the Reformation, erasing centuries of ascetical tradition. The bare cross, while symbolic, does not replace the living witness of religious life. Protestant communities rely on individual faith rather than communal sacrifice. This shift reflects a broader emphasis on personal assurance over collective endurance. The Catholic crucifix, by contrast, calls all believers to a shared mission of sacrifice.

The rejection of monasticism also affected Protestant culture. Without religious orders, there are fewer models of radical self-denial. Catholic saints, like Benedict or Clare, inspire the faithful through their embrace of the cross. Protestantism, while honoring figures like Luther or Wesley, lacks a tradition of ascetical heroes. This can make suffering seem less integral to faith. The bare cross, while affirming Christ’s triumph, does not challenge believers to live sacrificially in the same way. Catholic religious life, centered on the crucifix, offers a visible reminder of this call. The absence of such witnesses in Protestantism reinforces a theology focused on victory. This difference is particularly stark in times of crisis, when sacrifice becomes essential. The crucifix remains a powerful call to endurance for Catholics.

Protestant Worship and Architecture

Protestant worship often lacks the sacrificial themes central to Catholic liturgy. The Mass, with its re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice, is absent in most Protestant traditions (CCC 1367). Communion, when observed, is typically symbolic, not a participation in Calvary. This reduces the connection to Christ’s suffering. Protestant services focus on preaching, music, and prayer, creating an atmosphere of celebration. The bare cross, if present, reinforces this emphasis on resurrection. There is no altar, no crucifix, and no visible link to the Passion. This contrasts with Catholic worship, where the crucifix and Eucharist keep the cross central. The absence of sacrificial imagery shapes a different spiritual experience. Protestant worship, while vibrant, often prioritizes comfort over contemplation of suffering.

Protestant church architecture reflects this theology. Many Protestant churches are plain, with minimal decoration. The crucifix is replaced by a bare cross or no symbol at all. Saints, who model sacrificial lives, are absent from Protestant spaces. This creates an environment focused on simplicity and accessibility. However, it also removes reminders of suffering and sacrifice. Catholic churches, with their stations of the cross, relics, and crucifixes, invite contemplation of the cross. The contrast is striking when comparing a Gothic cathedral to a modern Protestant auditorium. The Catholic space, centered on the crucifix, challenges believers to embrace the cross. Protestant architecture, while functional, often prioritizes comfort, reflecting a theology less focused on suffering.

Cultural Implications of Protestant Theology

In Protestant-majority societies, particularly in the United States, the absence of a theology of suffering has cultural consequences. The prosperity gospel, which equates faith with wealth and health, is a prominent example. This teaching, popular in some evangelical circles, directly opposes the Catholic view of suffering as redemptive. The bare cross, while affirming Christ’s victory, does not challenge this mindset. As a result, suffering is often seen as something to eliminate, not sanctify. Catholic theology, rooted in the crucifix, offers a countercultural perspective. It teaches that trials are a path to holiness, not a sign of failure. This difference shapes attitudes toward illness, poverty, and hardship. Protestant communities may struggle to find meaning in suffering without a theology of the cross. The crucifix, by contrast, provides Catholics with a framework for endurance.

The focus on individual comfort in Protestant culture also affects social priorities. Catholic tradition, with its emphasis on the cross, encourages service to the poor and marginalized. Religious orders and lay movements, inspired by the crucifix, have historically led these efforts. Protestant communities, while active in charity, often frame it as an expression of faith rather than a share in Christ’s suffering. The bare cross does not call for the same level of sacrifice. This can lead to a Christianity more focused on personal success than communal responsibility. The Catholic crucifix, by contrast, reminds believers that love involves sacrifice. This theology has shaped Catholic social teaching, which emphasizes solidarity with the suffering (CCC 1939). The absence of this perspective in Protestantism reflects a broader theological divide.

Conclusion: The Crucifix as a Call to Transformation

The crucifix is more than a symbol; it is a call to live the cross daily. For Catholics, it embodies the theology of suffering as a path to salvation. The Protestant bare cross, while affirming resurrection, does not convey the same invitation to sacrifice. This difference reveals a fundamental divergence in how the two traditions understand Christian life. Catholics see suffering as participatory, uniting believers with Christ’s redemptive work. Protestants, emphasizing sola fide, often view suffering as a past event or an obstacle. The crucifix challenges Catholics to embrace their trials, while the bare cross offers assurance of victory. Both perspectives have value, but the crucifix provides a fuller picture of discipleship. It reminds believers that there is no salvation without the cross. As Luke 9:23 teaches, following Christ means taking up the cross daily, a call vividly captured by the crucifix.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.