Brief Overview

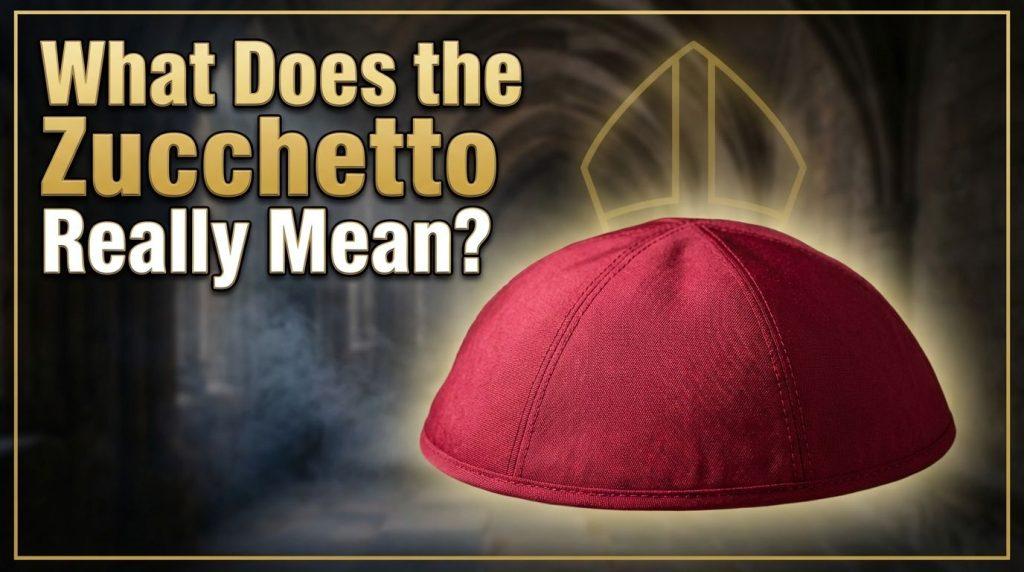

- The zucchetto is a small skullcap worn by Catholic clergy as a sign of their ecclesiastical rank and commitment to the Church’s hierarchical structure.

- Different colors of zucchetti indicate different levels of ordained ministry, with white for the Pope, scarlet for cardinals, violet for bishops, and black for priests.

- This distinctive headwear has roots in practical needs but evolved to carry deep symbolic meaning within Catholic tradition and liturgical practice.

- The zucchetto remains on the head during most liturgical functions but is removed at specific moments that hold particular sacramental or theological significance.

- Understanding when and why clergy wear the zucchetto helps Catholics recognize the visible order and structure that Christ established for His Church.

- This simple piece of fabric communicates complex truths about authority, humility, service, and the sacred character imparted through Holy Orders.

Historical Development and Origins

The zucchetto emerged in the medieval period as a practical solution to a common problem faced by clergy who had tonsured heads. Tonsure was the practice of shaving the crown of the head as a visible sign of renunciation of worldly vanity and dedication to religious life. This exposed scalp made clergy vulnerable to cold temperatures, especially in the large, drafty stone churches and monasteries of medieval Europe. Priests and monks began wearing simple cloth caps to protect their heads while maintaining their tonsured appearance. These early head coverings were purely functional items without the symbolic significance they would later acquire. The caps were typically made from whatever fabric was available locally and showed little standardization in color or design. Over time, as the Church developed more elaborate liturgical customs and clerical dress codes, these practical caps became formalized. The term “zucchetto” comes from the Italian word for a small gourd or pumpkin, referring to the cap’s rounded shape. By the Renaissance period, clear rules governed who could wear which color, transforming a practical item into a status symbol. The zucchetto became part of the Church’s visual language, communicating hierarchy and order through color-coded headwear.

The practice of wearing the zucchetto spread throughout the Latin Church as liturgical customs became more uniform and regulated. Different religious orders and regional churches initially maintained varying practices regarding clerical headwear and dress. The Council of Trent in the sixteenth century brought greater standardization to many aspects of Catholic worship and clerical life. While Trent did not specifically mandate the zucchetto, the post-Tridentine period saw increased attention to proper clerical attire and dignified worship. Bishops and cardinals adopted more consistent practices in their vestments and insignia of office. The color coding system became firmly established, creating a visual hierarchy that anyone could understand at a glance. A white zucchetto immediately identified the Pope, even in a crowd of other clergy at major Church gatherings. Cardinals in their scarlet caps stood out as the Pope’s closest advisors and electors of future popes. Bishops wore violet to distinguish themselves from ordinary priests, who wore black if they wore zucchetti at all. This system reinforced the Church’s hierarchical structure established by Christ and developed through apostolic tradition (CCC 874-896). The zucchetto thus became more than headwear; it became a teaching tool about ecclesial order and authority.

Theological Symbolism and Meaning

The zucchetto carries multiple layers of symbolic meaning that reflect Catholic understanding of ordained ministry and ecclesial authority. At its most basic level, the zucchetto signifies that the wearer has received the sacrament of Holy Orders and occupies a specific place in the Church’s hierarchy. The different colors create a visible representation of the levels of authority from the Pope down through cardinals and bishops to priests. This visual hierarchy reminds everyone that the Church operates according to divinely established order rather than democratic principles or personal preference. Christ chose twelve apostles and gave them authority to teach, sanctify, and govern in His name (Matthew 28:18-20). The apostles in turn ordained successors and established the pattern of episcopal leadership that continues today. The zucchetto makes this apostolic succession visible to the eye, showing that authority passes from one generation to the next through sacramental ordination. When Catholics see their bishop wearing his violet zucchetto, they recognize him as a successor to the apostles with the fullness of Holy Orders. The color distinguishes him from priests, who share in the bishop’s ministry but do not possess the same degree of sacramental power.

The act of covering the head also carries biblical and traditional meaning related to reverence and humility before God. In ancient Jewish practice, covering the head during prayer expressed recognition of God’s transcendence and one’s own smallness before the divine majesty. Christian tradition developed its own customs around head covering, with different practices for clergy and laity, men and women. The clergy’s zucchetto represents their special consecration to God’s service and their position as mediators between God and the people. By covering their heads, clergy acknowledge that their authority comes from above, from God rather than from themselves or the people they serve. The small size of the zucchetto suggests humility; it covers only the crown of the head rather than making a bold fashion statement. The simple design without excessive ornamentation keeps attention focused on what the zucchetto represents rather than on the object itself. Even papal zucchetti remain relatively plain despite being made from fine materials, reflecting that sacred ministry calls for dignity without ostentation. The symbolism thus balances recognition of clerical authority with reminders of the humility and service that should characterize all Christian leadership.

Color Distinctions and Hierarchical Meaning

The white zucchetto worn exclusively by the Pope carries profound symbolism related to his unique role as successor of Saint Peter and Vicar of Christ on earth. White signifies purity, holiness, and the fullness of authority vested in the papal office as supreme pastor of the universal Church. Only one living person at any time wears the white zucchetto, making it instantly identifiable and unmistakable in any gathering. The Pope’s white vestments and zucchetto set him apart visually from all other clergy, emphasizing the singular nature of his ministry. This distinctive color reflects the Catholic belief that Christ established the papacy as the visible principle and foundation of Church unity (CCC 882). The white zucchetto has become so associated with the papal office that Catholics worldwide immediately recognize it. When a new pope appears on the loggia of Saint Peter’s Basilica after his election, the white zucchetto confirms his acceptance of the office. The simplicity of this small white cap contrasts with the enormous spiritual authority it represents, creating a powerful visual paradox. Popes throughout history have worn this distinctive headwear as a sign of their burden and privilege as Christ’s Vicar.

Cardinals wear scarlet or red zucchetti that symbolize their willingness to shed their blood for Christ and His Church. This crimson color recalls the martyrs who gave the ultimate witness to their faith through violent death. Cardinals form the College that elects new popes and serves as the Pope’s closest advisors in governing the universal Church. Their red zucchetti identify them as members of this elite body with special responsibilities and privileges. The color choice reminds cardinals that their office may demand the highest sacrifice if circumstances require it. Many cardinals throughout history have indeed faced persecution, imprisonment, or martyrdom for their faith and ministry. The red zucchetto thus carries both honor and sobering responsibility, marking those who stand closest to the Pope in the Church’s governance. When Catholics see a cardinal’s red zucchetto, they recognize someone who has been elevated to the highest ranks of Church leadership. This visual identification helps maintain proper protocol and respect in ecclesiastical gatherings and public events. The scarlet color also creates visual harmony with cardinals’ other distinctive garments and insignia.

Bishops wear violet or amaranth zucchetti that distinguish them from both cardinals above and priests below in the hierarchical structure. This purple-red color has ancient associations with royalty and nobility, fitting for those who possess the fullness of the priesthood. Bishops receive the complete sacrament of Holy Orders, including the power to ordain other clergy and confirm the baptized (CCC 1536-1538). Their violet zucchetti mark them as successors to the apostles with authority to teach, sanctify, and govern their dioceses. The color choice creates clear visual distinction while avoiding confusion with either papal white or cardinalatial red. When multiple bishops gather for meetings or liturgies, their identical violet zucchetti express their collegial unity as members of the episcopal college. Yet each bishop exercises authority in his own diocese, where his zucchetto identifies him as the chief shepherd. Auxiliary bishops and coadjutor bishops wear the same violet as diocesan bishops, as they all share equally in episcopal orders regardless of jurisdiction. The violet zucchetto thus communicates both the dignity of episcopal office and the unity of bishops with one another and with the Pope.

Priests may wear black zucchetti, though this practice varies considerably based on local custom and personal preference. The black color indicates their clerical state without claiming the higher ranks of bishop or cardinal. Many priests choose not to wear zucchetti at all, viewing them as unnecessary or preferring simpler clerical attire. Religious order priests sometimes follow their community’s customs regarding head covering rather than universal norms. Diocesan priests typically wear black zucchetti only during formal liturgical functions or official Church gatherings. The black color maintains modesty and avoids any appearance of claiming authority beyond what ordination to the priesthood actually confers. Priests serve essential roles in the Church’s mission but remain subordinate to bishops in the hierarchical structure. Their black zucchetti when worn express participation in the clerical state while respecting proper distinctions of rank and responsibility. Some traditional priests wear the zucchetto regularly as part of maintaining formal clerical dress in public. Others reserve it strictly for liturgical contexts where proper vesture matters most. The varying practices reflect legitimate diversity within overall unity on essential matters.

Proper Use During Liturgical Functions

The zucchetto remains on the head during most of the Mass and other liturgical celebrations, with specific moments when it must be removed. Understanding these rules helps Catholics appreciate the gesture’s significance and the theology behind ceremonial actions. The general principle holds that the zucchetto stays on during ordinary parts of the liturgy but comes off for the most sacred moments. During the entrance procession and opening prayers, clergy keep their zucchetti in place as they move to their positions. The Liturgy of the Word proceeds with zucchetti on, including during the readings and homily. When the bishop preaches, he wears his violet zucchetto as a sign of his teaching authority and office. Priests likewise keep their black zucchetti on while delivering homilies, though again many priests do not wear them at all. The rules become more specific during the Liturgy of the Eucharist, the heart of the Mass. Clergy remove their zucchetti during the Eucharistic Prayer, from the preface dialogue through the great Amen. This removal expresses profound reverence for the sacred mystery taking place at the altar as bread and wine become Christ’s Body and Blood.

The theological reasoning behind removing the zucchetto during the Eucharistic Prayer connects to ancient practices of uncovering the head before God. The principle appears in Saint Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, where he discusses head covering practices during worship (1 Corinthians 11:4-7). While the specific applications have varied across times and cultures, the underlying concept of showing reverence through head covering or uncovering remains. During the most sacred moment of the Mass, when heaven and earth meet in the Eucharistic sacrifice, clergy bare their heads in awe. This gesture acknowledges that they stand on holy ground, in the very presence of God made flesh. The removal happens discretely and reverently, without drawing attention or disrupting the prayer’s flow. After communion and during the final blessing, clergy replace their zucchetti for the concluding rites. The on-again, off-again pattern might seem arbitrary but actually follows careful liturgical logic about when reverence demands different postures. These rules developed over centuries through the Church’s lived experience of worship and reflection on proper ceremony. Modern liturgical reforms maintained most traditional zucchetto practices while simplifying some overly complex regulations. The current discipline balances respect for tradition with pastoral practicality and theological soundness.

Outside of Mass, zucchetto practices vary depending on the specific liturgical action or ceremony taking place. During the Liturgy of the Hours, clergy generally keep their zucchetti on throughout the office. Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament follows similar rules to Mass, with removal during the elevation and blessing. When administering sacraments like baptism or matrimony, priests typically wear their zucchetti as signs of their official capacity. Bishops always wear their violet zucchetti when performing confirmations, ordinations, and other episcopal functions. The zucchetto stays on during processions, formal receptions, and other ceremonial occasions. Clergy remove their zucchetti when praying before the exposed Blessed Sacrament in personal devotion. They also uncover when receiving communion themselves, showing reverence for Christ truly present in the Eucharist. Entering a chapel for private prayer generally calls for removing the zucchetto as one would any hat. These various practices reflect the principle that the zucchetto serves liturgical and official functions rather than being ordinary headwear. The distinctions might seem subtle but carry real meaning about sacred versus ordinary time and space.

The Zucchetto and Papal Traditions

Popes have developed unique customs around the zucchetto that reflect both its practical function and symbolic significance. The tradition of throwing the papal zucchetto into crowds during audiences became associated especially with Pope John Paul II. When pilgrims would gift the Pope their own zucchetti, he would sometimes wear them briefly and then toss them back as blessed souvenirs. These papal zucchetti became prized possessions for those lucky enough to catch them, treasured as tangible connections to the Holy Father. The practice demonstrated the Pope’s warmth and accessibility while maintaining the dignity of his office. Pope Benedict XVI continued occasional zucchetto exchanges, though with his characteristic reserve and formality. Pope Francis has brought his own style to wearing the zucchetto, sometimes choosing simpler versions that reflect his emphasis on humility. The white zucchetto remains constant across different papal personalities and styles, showing how the office transcends individual preferences. Each pope must wear the white cap regardless of his personal comfort or fashion sense.

The papal zucchetto plays a role in various ceremonies and traditions beyond ordinary liturgical use. When a new pope is elected, one of the first acts involves placing the white zucchetto on his head along with other papal insignia. This physical gesture marks the moment when the chosen cardinal accepts the burden and honor of the papacy. The zucchetto remains visible throughout the new pope’s first appearance to the world from the Vatican loggia. During papal funerals, the deceased pope’s zucchetto is placed with his body as a sign of the office he held in life. The tradition of burying popes with their zucchetti maintains continuity with their earthly ministry even in death. When popes meet with heads of state and other dignitaries, the white zucchetto identifies them instantly in official photographs and news coverage. The simple white cap appears in countless images of popes greeting crowds, blessing the faithful, and celebrating Mass. It has become so iconic that political cartoonists and artists use it as shorthand for the papacy itself. The zucchetto thus functions as both practical headwear and powerful symbol recognized worldwide.

Regional and Cultural Variations

While the basic color system for zucchetti remains standard throughout the Latin Church, some regional variations exist in materials and styles. Italian zucchetti traditionally use watered silk or similar fine fabrics that drape smoothly over the head. Northern European versions sometimes employ heavier materials suited to colder climates and different aesthetic preferences. The construction methods vary slightly, with some zucchetti featuring eight triangular panels and others using different sectioning. The precise shade of violet for bishops’ zucchetti can range from purple-red to blue-purple depending on manufacturer and tradition. Cardinals’ red likewise spans from true scarlet to deeper crimson shades. These variations cause no theological problems, as the essential color distinction remains clear and recognizable. Local workshops and suppliers produce zucchetti according to regional craft traditions and available materials. Some bishops commission custom zucchetti from particular artisans they wish to support or whose work they admire. The resulting diversity in style and quality reflects legitimate pluralism within Catholic unity on essentials.

Eastern Catholic churches have their own distinctive traditions regarding clerical headwear that differ from Latin practices. Byzantine bishops wear a crown-like headpiece called a mitre that serves similar symbolic functions to the Latin zucchetto. Eastern clergy generally do not use zucchetti at all, following their own liturgical customs and dress codes. When Eastern Catholic bishops attend meetings with Latin bishops, the visual differences in headwear highlight the Church’s unity in diversity. Catholic unity does not require absolute uniformity in every practice but rather communion in faith and sacraments. The various Eastern Catholic churches maintain their ancient traditions while in full communion with the Pope. Their different approaches to clerical dress, including headwear, enrich the universal Church with particular cultural and theological gifts. Latin Catholics can learn from Eastern traditions just as Eastern Catholics may appreciate aspects of Latin practice. The zucchetto represents specifically Latin Catholic tradition rather than universal Christian custom, an important distinction to maintain. Understanding these differences prevents confusion and promotes authentic appreciation for Catholic diversity.

Modern Controversies and Debates

Contemporary discussions about clerical dress including the zucchetto often intersect with broader debates about clericalism and privilege in the Church. Some Catholics argue that distinctive clerical clothing creates unhealthy separation between clergy and laity. They worry that symbols of rank like colored zucchetti reinforce hierarchical thinking that contradicts Gospel equality. Progressive voices sometimes advocate for simpler clerical dress that minimizes visible distinctions and status symbols. They point to Jesus washing the apostles’ feet as the model for Christian leadership through humble service. These critics note that elaborate vestments and insignia can tempt clergy toward vanity and superiority rather than Christlike humility. The sex abuse crisis intensified these concerns, as some saw clericalism and unaccountable power as contributing factors. Reformers argue that reducing external symbols of clerical privilege might help create healthier relationships between clergy and people. They suggest that priests and bishops should dress simply to emphasize their service rather than authority or status.

Traditional Catholics defend the zucchetto and other clerical dress as legitimate expressions of sacred order and proper reverence. They argue that visible symbols help people recognize and respect ordained ministry as distinct from lay vocations. The hierarchical structure reflected in colored zucchetti comes from Christ’s establishment of the apostles and their successors. Eliminating these symbols would not eliminate the reality of hierarchical authority but would obscure it visually. Defenders note that legitimate authority deserves appropriate symbols, just as judges wear robes and military officers wear rank insignia. The problem lies not in symbols themselves but in how individuals use or abuse the authority symbolized. Holy bishops who wear violet zucchetti humbly demonstrate that the problem is moral rather than symbolic. Removing external signs would not necessarily produce holier or more humble clergy. Traditional voices worry that eliminating distinctive clerical dress represents capitulation to secular values that deny sacred ministry’s special character. They maintain that proper symbols, properly understood and used, serve the Church’s mission and help people recognize Christ’s presence in ordained ministers.

Practical Aspects and Etiquette

Clergy must learn proper etiquette for wearing and handling the zucchetto in various contexts and situations. The cap should fit snugly enough to stay in place during normal movement but not so tightly as to cause discomfort. Proper placement centers the zucchetto on the crown of the head, covering the traditional tonsure location. Clergy should avoid fussing with their zucchetti during liturgical functions, as this draws inappropriate attention. When removing the zucchetto, the proper gesture involves a simple, dignified motion without flourish or drama. Some clergy hold the removed zucchetto in their hands while others place it on a nearby surface. During concelebrated Masses, all clergy should follow the same practice regarding when to remove and replace zucchetti. Servers or assistants never handle the bishop’s zucchetto except in specific circumstances where protocol requires assistance. The zucchetto should be stored properly when not in use, maintaining its shape and protecting it from damage. Replacement becomes necessary when a zucchetto becomes worn, stained, or loses its proper appearance. These practical details might seem trivial but actually matter for maintaining dignity in sacred functions.

Protocol questions sometimes arise regarding who bows or shows reverence to whom, with the zucchetto serving as a visual indicator. When clergy of different ranks meet, the zucchetto colors immediately establish proper precedence and courtesy. Priests bow to bishops, bishops to cardinals, and cardinals to the Pope, with the zucchetto confirming who holds which rank. A bishop visiting a parish wears his violet zucchetto to indicate his official presence and authority. Priests in his presence recognize his rank and show appropriate respect regardless of age or personal relationship. The zucchetto thus facilitates proper order in clerical interactions and public functions. When popes meet with cardinals, the white and red zucchetti create a visual tableau of Church hierarchy in action. Photographers capturing these moments document the living structure of Catholic ecclesial life. The colors work together to create understanding about relationships, authority, and communion within the hierarchical Church. These visual elements communicate truths that words alone might not convey as effectively or immediately.

The Zucchetto as Teaching Tool

The zucchetto provides Catholic educators with a concrete object for teaching about Church structure and ordained ministry. Children can easily understand that different colored caps mean different jobs and responsibilities in the Church. Teachers can use the color coding to explain the hierarchy from Pope through cardinals and bishops to priests. Visual learners especially benefit from this tangible symbol that makes abstract concepts concrete and memorable. The zucchetto appears in pictures, videos, and live encounters, providing repeated exposure to this symbol’s meaning. Students who learn about the zucchetto in religious education class will recognize it when they see bishops at confirmations. This recognition helps them understand that the bishop comes in his official capacity to perform this sacrament. The white zucchetto in news coverage of the Pope becomes meaningful rather than merely decorative. Young Catholics develop visual literacy in Church symbols that aids their lifelong faith formation. Parents can point out zucchetti to children during televised Masses or diocesan events, creating teaching moments. These informal lessons build understanding over time through accumulated small encounters with the symbol.

Adult faith formation likewise benefits from exploring the zucchetto’s history, symbolism, and proper use in Catholic tradition. Many adult Catholics have observed zucchetti for years without understanding their specific meanings or significance. Learning about the color distinctions and liturgical protocols deepens appreciation for the Church’s carefully developed customs. The zucchetto provides an entry point for discussing broader topics like apostolic succession and ecclesial authority. Teachers can connect the physical symbol to theological realities like the sacramental character imparted by Holy Orders (CCC 1581-1584). Understanding why clergy remove zucchetti during the Eucharistic Prayer leads to reflection on reverence and the Real Presence. These connections show how external symbols serve internal spiritual realities rather than existing as mere decoration. Study groups examining Church tradition can investigate how the zucchetto evolved from practical headwear to sacred symbol. Historical research reveals how the Church adapts and develops its practices while maintaining continuity with the past. Such investigations help Catholics appreciate that tradition lives and grows rather than remaining static and unchanged. The simple zucchetto thus opens windows into rich theological and historical understanding.

Relationship to Other Clerical Insignia

The zucchetto forms part of a broader system of clerical dress and insignia that communicate rank and function. Bishops also wear pectoral crosses, rings, and mitres that identify their episcopal dignity. Cardinals receive red hats called galeros traditionally, though these are now largely ceremonial rather than actually worn. The zucchetto coordinates with these other symbols to create a complete visual language of ecclesial office. When a bishop vests fully for pontifical Mass, his violet zucchetto matches other purple elements in his attire. The coordination creates visual harmony that reflects the integrated nature of his episcopal ministry. Cardinals’ red zucchetti match their red cassocks, creating immediate recognition of their elevated rank. Priests in black zucchetti typically wear black cassocks or clerical suits, maintaining simple dignity. The color scheme throughout clerical dress follows consistent principles that make the system easily readable. Someone unfamiliar with Catholic practice can still grasp basic distinctions through these visual cues.

The zucchetto’s small size contrasts with the larger mitre worn by bishops during solemn liturgies. The mitre’s impressive height and ornate decoration emphasize the bishop’s teaching and sanctifying authority. The zucchetto’s modest profile suggests the humility that should accompany such authority. Bishops typically remove their mitres when not actually performing liturgical actions, returning to the simpler zucchetto. This alternation between grand and simple headwear reflects the dual nature of episcopal ministry. Bishops must exercise real authority while remaining humble servants of the servants of God. The changing headwear helps bishops themselves remember these different aspects of their calling. When the elaborate mitre comes off, the small zucchetto remains as a baseline symbol of clerical state. The pectoral cross worn by bishops stays constant whether they wear zucchetto or mitre, symbolizing that all authority flows from Christ’s cross. These various symbols work together as an integrated system rather than isolated decorative elements.

Contemporary Practice and Future Directions

Current practice regarding the zucchetto varies considerably based on geographical location and clerical generation. Older clergy who received their formation before the Second Vatican Council generally maintain more traditional dress codes. They typically wear their zucchetti regularly as part of proper clerical attire in public settings. Younger priests often adopt more casual approaches to clerical dress, wearing zucchetti only during formal liturgies if at all. This generational divide reflects broader questions about clerical identity and public witness in secular societies. Some bishops encourage their priests to wear clerical dress including zucchetti as visible signs of their sacred calling. Others allow considerable freedom, recognizing that cultural contexts differ regarding appropriate public religious dress. The debate touches fundamental questions about how clergy should present themselves in contemporary culture. Should they stand out as visibly different or blend in to relate better with ordinary people? The zucchetto becomes a focal point for these larger discussions about priesthood and ministry today.

Future developments regarding the zucchetto remain uncertain as the Church continues discerning how to maintain tradition while addressing modern realities. Some predict declining use of zucchetti among ordinary clergy while bishops maintain the practice. Others foresee renewed appreciation for traditional clerical dress among younger priests attracted to clear Catholic identity. Liturgical movements favoring greater solemnity and reverence might increase zucchetto use at Masses and ceremonies. Conversely, continued emphasis on simplicity and accessibility might further reduce reliance on formal clerical attire. The color coding system seems likely to persist as long as the hierarchical structure it represents remains. Future popes will certainly continue wearing white zucchetti regardless of their personal preferences or styles. Cardinals and bishops likewise will maintain their distinctive colors during their tenures in office. The question centers more on how regularly these caps appear and how much significance people attach to them. Whatever changes occur, the zucchetto will likely remain part of Catholic tradition even if its actual use fluctuates. The Church’s long history shows that practices can fade and revive across generations without losing their essential meaning or validity.

Spiritual Significance for Clergy

For clergy themselves, the zucchetto can serve as a daily reminder of their sacred calling and responsibilities. Each time a bishop places his violet zucchetto on his head, he can recall his ordination and the grace received. The weight of the cap, however slight, symbolizes the weight of souls entrusted to his care. The color distinguishing him from others reminds him that he serves in a unique capacity with specific duties. Priests who wear black zucchetti likewise have opportunities for spiritual reflection on their ordained identity. The simple act of putting on or removing the zucchetto can become a moment of prayer and renewal. Clergy might pray briefly each time, asking God’s help in fulfilling their ministry faithfully. The zucchetto on their heads while celebrating Mass reminds them that they act in persona Christi, in the person of Christ. This awareness should produce humility and reverence rather than pride or self-importance. The external symbol points toward internal realities of grace and responsibility that define ordained ministry.

The danger of the zucchetto lies in its potential to feed vanity or create false security about one’s spiritual state. Wearing the correct color does not automatically make someone holy or faithful to their calling. Church history includes bishops and cardinals who wore proper insignia while living scandalously or neglecting their duties. The external symbol means nothing if not accompanied by genuine conversion of heart and faithful service. Clergy must constantly examine whether their use of symbols like the zucchetto reflects true humility or hidden pride. The temptation to value position and honor above service and sacrifice affects every human being in leadership. Ordained ministers need special vigilance precisely because they deal with sacred things that can become occasions for spiritual danger. Saints who served as bishops often wrote about struggling with temptations particular to high office. They recognized that wearing the violet zucchetto brought both grace and testing, privilege and burden. Modern clergy inherit these same challenges and must likewise depend on God’s grace rather than external symbols. The zucchetto serves well when it prompts humility, poorly when it encourages self-satisfaction or superiority.

Conclusion

The zucchetto endures as a meaningful symbol in Catholic tradition despite changing times and varying opinions about its value. This simple skullcap communicates complex truths about Church structure, ordained ministry, and sacred authority through its colors and use. Catholics who understand the zucchetto can read the visual language of clerical dress and recognize the hierarchy Christ established. The white, red, violet, and black caps create a spectrum of meaning from papal supremacy through episcopal and presbyteral ministry. These colors appeared throughout centuries of Church history, connecting contemporary Catholics to their ancestors in faith. The zucchetto’s practical origins remind us that sacred symbols often begin with human needs before acquiring deeper significance. The development from warming cap to ecclesiastical insignia shows how the Church sanctifies ordinary things for spiritual purposes. Future generations will inherit these symbols and decide how to maintain or adapt them for new contexts. The essential realities of ordained ministry and Church hierarchy will persist regardless of whether particular symbols continue. Yet symbols matter because humans are embodied creatures who need visible signs of invisible realities.

The zucchetto ultimately points beyond itself to the divine authority that flows through the Church’s hierarchical structure. Christ established His Church on the foundation of the apostles, giving them power to teach, sanctify, and govern in His name (Matthew 16:18-19). The apostles ordained successors who continued this ministry across generations through unbroken apostolic succession (CCC 861-862). Today’s bishops wearing violet zucchetti stand in that line of succession, carrying authority that traces back to the apostles themselves. The papal white zucchetto represents the unique Petrine ministry that ensures Church unity and maintains definitive teaching authority. These colorful caps make visible the invisible grace and authority conferred through sacramental ordination. They remind Catholics that the Church exists as a hierarchical communion rather than a democracy or voluntary association. Whether one views this positively or critically depends partly on how one understands Christ’s intentions for His Church. The Catholic faith maintains that hierarchy serves the Church’s mission when exercised according to Gospel principles of humble service. The zucchetto worn properly symbolizes this servant leadership, pointing always toward Christ the true head of the Church. May all who see these distinctive caps remember that genuine authority in the Church exists only to serve God’s people and advance Christ’s kingdom, now and always.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.