Brief Overview

- The Pax symbol refers to several distinct Christian symbols related to the Latin word for peace, most commonly the Chi Rho monogram or liturgical objects used in Catholic worship.

- The Chi Rho combines the first two Greek letters of Christ’s name and became one of the earliest Christian symbols after Emperor Constantine’s vision before the Battle of Milvian Bridge.

- During the Middle Ages, the pax board was a decorated tablet or plate kissed during Mass to transmit the peace of Christ from the altar to the congregation.

- The word “pax” itself means peace in Latin and appears in liturgical greetings such as “pax vobis” and “pax vobiscum,” meaning peace to you or peace be with you.

- Catholic teaching emphasizes that true peace comes from Christ and extends beyond merely the absence of conflict to include justice, charity, and respect for human dignity.

- Understanding the Pax symbol requires recognizing its multiple layers of meaning within Catholic tradition, from visual representation to liturgical practice to theological concept.

The Historical Origins of Christian Peace Symbols

The Pax symbol has ancient roots that stretch back to the earliest days of Christianity, when believers needed ways to identify themselves and express their faith amid persecution. The most recognizable form of the Pax symbol is the Chi Rho, which combines the Greek letters X and P to create a monogram representing Christ. These letters are the first two characters in the Greek word for Christ, which is written as ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ. Early Christians adopted this symbol as a shorthand way to reference their Savior without drawing unwanted attention from Roman authorities who viewed Christianity as a threat to the empire. The symbol appeared in the Roman catacombs, scratched into walls and carved onto tombs, serving as a quiet testimony to faith during times of danger. Christians used such symbols to mark meeting places, identify fellow believers, and decorate burial sites with reminders of their hope in resurrection. The Chi Rho was not merely decorative but carried theological weight, proclaiming that Jesus Christ was the source of salvation and peace. Over time, as Christianity moved from persecuted sect to established religion, these symbols emerged from the shadows and took their place in public worship. The transformation of the Chi Rho from secret sign to public proclamation mirrors the broader story of Christian witness in the Roman world.

The Chi Rho gained prominence through a dramatic historical event that changed the course of Western civilization. In the year 312, the Roman Emperor Constantine marched toward Rome to face his rival Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge. According to the historian Eusebius of Caesarea, Constantine and his soldiers experienced a vision in which they saw the Chi Rho symbol in the sky, accompanied by words that promised victory if they fought under this sign. Constantine ordered his soldiers to paint the symbol on their shields, and his army won a decisive victory that made him sole ruler of the Western Roman Empire. This event marked a turning point for Christianity, as Constantine became the first Roman emperor to favor the faith and eventually converted himself. The Chi Rho symbol became closely associated with imperial authority and Christian triumph, appearing on coins, standards, and public monuments throughout the empire. Some scholars note that variations of the symbol existed before Christianity and were used to mark important passages in manuscripts, but Constantine’s adoption gave it specifically Christian meaning. The blending of military victory with Christian symbolism created tension that would persist throughout Church history, as believers wrestled with how to reconcile the peaceful teachings of Christ with the realities of political power. Nevertheless, the Chi Rho became permanently established as a symbol of Christ’s peace and authority over all earthly powers.

The Chi Rho as Christogram

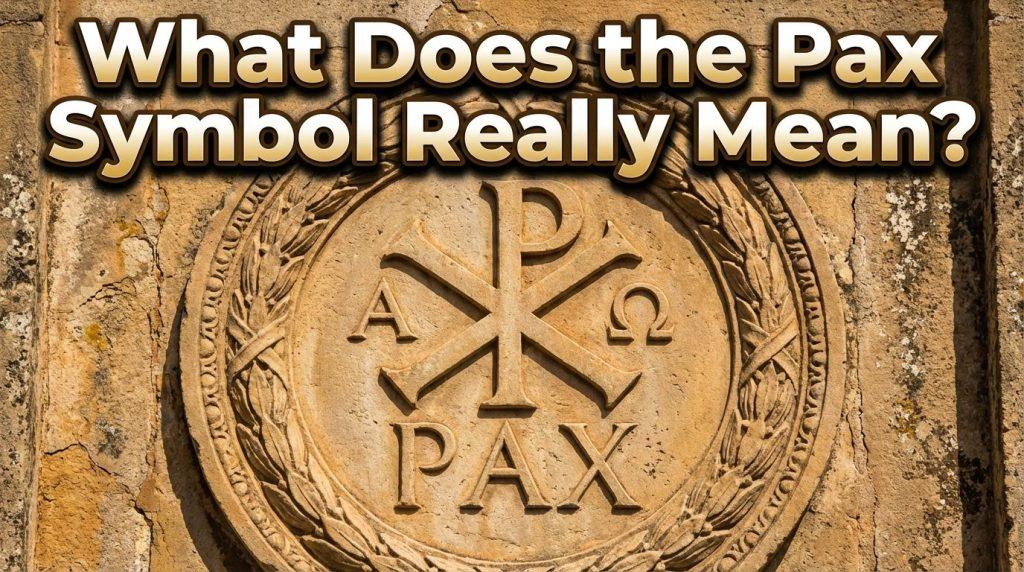

The Chi Rho functions as what scholars call a Christogram, which is a combination of letters that forms an abbreviation or symbolic representation of Jesus Christ. The beauty of this symbol lies in its simplicity and clarity, as anyone familiar with Greek letters would immediately recognize the reference to Christ. Over the centuries, artists and craftspeople have created countless variations on the basic Chi Rho design, adapting it to different contexts and artistic styles. Some versions shape the P to resemble a shepherd’s staff, evoking Christ’s role as the Good Shepherd who guides and protects his flock. Other versions incorporate the Latin word “pax” directly into the monogram, making the connection between Christ and peace explicit. By removing one arm of the X, some designs reveal a hidden cross, emphasizing Christ’s redemptive sacrifice on Calvary. The Alpha and Omega letters often accompany the Chi Rho, referring to Christ as the beginning and end of all things as described in the Book of Revelation. This flexibility allowed the symbol to serve different purposes in different settings, from grand church decorations to simple personal devotions. The Chi Rho appears on vestments worn by clergy, carved into church furniture, woven into altar cloths, and etched onto liturgical vessels. Its presence reminds worshipers that everything in the Church belongs to Christ and serves his purposes.

The theological meaning embedded in the Chi Rho extends beyond simple identification to make profound statements about the nature of Christ and his relationship to believers. When early Christians used this symbol, they proclaimed that Jesus was the Christos, the Anointed One promised by the prophets of Israel. The Greek word Christos translates the Hebrew word Messiah, connecting Jesus to centuries of Jewish hope for a savior who would restore God’s people. By using the first letters of this title, Christians affirmed their belief that Jesus fulfilled these ancient prophecies and brought God’s kingdom to earth. The symbol also emphasized the unity between Jesus and his followers, as those who belong to Christ share in his identity and mission. When a Christian saw the Chi Rho carved into a tomb or painted on a wall, it served as a reminder that death had no final power over those united with Christ. The symbol conveyed hope that resurrection awaited all who trusted in him. This connection between symbol and belief demonstrates how visual images can carry theological weight and shape the faith of communities. The Chi Rho was not merely decoration but a visible proclamation of core Christian convictions about who Jesus is and what he accomplished.

The Pax Board and Medieval Liturgical Practice

During the Middle Ages, the term “pax” took on a specific liturgical meaning related to the kiss of peace exchanged during Mass. In the early Church, clergy and congregation members shared an actual kiss as a sign of Christian unity and reconciliation before receiving Holy Communion. This practice reflected the biblical instruction to be reconciled with one’s brother before offering gifts at the altar. As the centuries passed, concerns about hygiene, propriety, and the practical difficulties of exchanging kisses in large congregations led to the development of alternative practices. By the thirteenth century, the physical embrace was replaced by the use of a special liturgical object called the pax board, pax tablet, or osculatory. This was typically a small rectangular tablet made from precious materials such as silver, gold, ivory, or carved wood, often decorated with religious imagery. The most common scenes depicted on pax boards included the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child, or various saints. The priest would kiss the altar during Mass, then kiss the pax board, thereby transferring the peace of Christ from the altar to the object. An assistant would then carry the pax board to other clergy and to members of the congregation, who would each kiss it in turn.

The theology behind the pax board ritual reveals important truths about how medieval Catholics understood the Mass and the nature of Christian community. The peace exchanged was not merely human goodwill or friendly greeting but specifically the peace of Christ himself, really present in the Eucharist on the altar. By kissing the altar and then the pax board, the priest served as mediator who transmitted Christ’s peace to the people. This practice emphasized the hierarchical structure of medieval worship while also affirming the unity of all believers in Christ. The pax board created a physical connection between the altar, where Christ became present through consecration, and the congregation gathered to receive him. The order in which people kissed the pax board often reflected social hierarchies, with persons of higher rank receiving it before those of lower status. This sometimes led to disputes and tensions, as people jealously guarded their place in the pecking order. Such conflicts ironically contradicted the very purpose of the peace ritual, which was meant to foster reconciliation and charity. The Church eventually suppressed or modified these practices in various ways, and the pax board fell out of common use after the Council of Trent reformed liturgical practices in the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, the pax board represents an important chapter in the history of Catholic worship and demonstrates how the Church has continually sought ways to make theological truths tangible and accessible to ordinary believers.

The Word Pax in Catholic Liturgy and Greeting

The Latin word “pax” permeates Catholic liturgical language and has shaped how Catholics greet one another and bless each other for two millennia. In the Mass, several instances of peace-related language appear, most notably in the greeting “Pax vobis” or “Pax vobiscum,” which the priest extends to the congregation. These phrases mean “Peace to you” or “Peace be with you,” echoing the words Jesus spoke to his disciples after the Resurrection. When Christ appeared to the frightened apostles gathered in the upper room, his first words were “Peace be with you,” as recorded in the Gospel of John. By repeating these words in the liturgy, the priest acts in the person of Christ, extending the Risen Lord’s peace to those assembled for worship. The congregation typically responds “Et cum spiritu tuo,” meaning “And with your spirit,” completing the exchange and affirming that the peace flows in both directions. This brief dialogue serves multiple purposes in the Mass, marking transitions between different parts of the liturgy, reminding worshipers of Christ’s presence among them, and reinforcing the bonds of charity that should unite all believers. The repetition of these formulaic greetings might seem rote, but their consistency across centuries and cultures creates a sense of continuity with the ancient Church and with Catholics around the world.

The greeting “pax” extends beyond formal liturgy into everyday Catholic life, particularly within religious communities. Saint Francis of Assisi famously used the phrase “Pax et bonum,” meaning “Peace and all good,” as his characteristic greeting to everyone he met. Francis began and ended his letters with this phrase, and Franciscan communities have preserved this custom for eight centuries. The greeting reflects Francis’s conviction that authentic peace cannot be separated from goodness, justice, and right relationship with God and neighbor. For Francis, peace was not passive tranquility but active commitment to living the Gospel and promoting harmony among all creatures. This Franciscan understanding of peace shaped Catholic social teaching and continues to influence how Catholics think about peacemaking today. Other religious orders developed their own variations on peace greetings, and monasteries often maintain traditions of exchanging peace at specific times or in particular ways. These practices remind Catholics that peace is both a gift from God and a responsibility to be lived out in daily life. The word “pax” thus functions as more than a simple greeting; it becomes a prayer, a blessing, and a commitment all at once.

Biblical Foundations of Christian Peace

The concept of peace expressed through the Pax symbol rests on solid biblical foundations that run throughout both Old and New Testaments. In the Hebrew Scriptures, the word “shalom” carries rich meaning that extends far beyond mere absence of conflict to encompass wholeness, completeness, prosperity, and right relationship between God and humanity. The prophets proclaimed visions of a coming age when God would establish perfect peace, when swords would be beaten into plowshares and nations would no longer learn war. These prophecies pointed toward the Messiah who would be called the Prince of Peace and would reign on David’s throne forever. Christians believe Jesus fulfilled these prophecies and inaugurated God’s kingdom of peace, though its fullness awaits the end of time. Throughout his earthly ministry, Jesus preached peace and blessed peacemakers, calling them children of God. He commanded his followers to love their enemies, pray for persecutors, and turn the other cheek rather than seeking revenge. These radical teachings challenged conventional wisdom about power and security, insisting that true peace comes through self-sacrificing love rather than coercion or violence. Jesus demonstrated this principle perfectly by accepting death on the cross to reconcile humanity with God.

The Gospel of John records Jesus telling his disciples, “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give to you. Let not your hearts be troubled, neither let them be afraid,” as found in John 14:27. This verse distinguishes between worldly peace, which depends on favorable circumstances and the absence of external threats, and the peace of Christ, which remains steady regardless of circumstances because it flows from trust in God’s love and power. Christ’s peace is fundamentally a gift, not an achievement, something received rather than earned through human effort. The letter to the Ephesians declares that Christ “is our peace,” as stated in Ephesians 2:14, and that through his death he broke down the dividing wall of hostility between different groups of people. This passage emphasizes that Christ’s work of reconciliation has cosmic scope, healing not only the breach between God and humanity but also the divisions that separate people from one another. The early Church understood itself as a community of peace where ethnic, social, and economic barriers were overcome through shared life in Christ. Saint Paul repeatedly encouraged believers to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace, recognizing that this unity required constant effort and mutual forgiveness. The biblical vision of peace thus encompasses personal tranquility, social harmony, and cosmic restoration, all made possible through Christ’s reconciling work.

Peace in the Catechism and Catholic Teaching

The Catechism of the Catholic Church develops a comprehensive theology of peace that builds on biblical foundations and centuries of reflection on Christian life in the world. The Catechism teaches that peace is not merely the absence of war but requires positive conditions including safeguarding human goods, free communication among people, respect for dignity, and the practice of fraternity (CCC 2304). This definition challenges simplistic notions of peace and insists that authentic peace demands justice, as peace cannot exist where fundamental human rights are violated or where inequality and oppression prevail. The Catechism describes peace as both “the tranquility of order” and “the work of justice,” borrowing from Saint Augustine and Pope Paul VI to emphasize that peace requires both proper ordering of society and active pursuit of what each person is owed. Furthermore, Catholic teaching insists that peace is “the effect of charity,” meaning that love must animate efforts at peacemaking for them to bear lasting fruit. Without charity, arrangements between parties remain fragile and prone to collapse when circumstances change or interests conflict. The Catechism’s treatment of peace thus weaves together philosophical, theological, and practical insights into a coherent vision.

The Catechism also teaches that earthly peace is an image and fruit of the peace of Christ, the messianic Prince of Peace who reconciled humanity with God through his blood shed on the cross (CCC 2305). This teaching grounds Catholic peacemaking in Christology, insisting that all genuine peace flows from and participates in Christ’s reconciling work. The Church herself becomes the sacrament of unity, a visible sign and instrument of the peace Christ came to bring. Catholics are called to be peacemakers as part of their baptismal vocation, imitating Christ who blessed those who work for peace. The Catechism acknowledges that violence and war remain tragic realities in a fallen world, but it insists on strict limits for the use of force and urges believers to prayer and action to free humanity from the ancient bondage of war (CCC 2307). The Church recognizes legitimate self-defense while simultaneously holding up the witness of those who renounce violence entirely and seek nonviolent means to protect human rights. This teaching preserves space for different vocations and approaches to peacemaking while maintaining that all must be animated by the same spirit of charity and respect for human dignity. Catholic peace teaching thus avoids both naive pacifism and callous acceptance of violence, charting a middle way grounded in realism about sin and hope in God’s grace.

The Sign of Peace in Contemporary Catholic Worship

The Second Vatican Council restored the sign of peace to the Mass in a form that differs from both the ancient kiss and the medieval pax board. In the current liturgy, the sign of peace occurs after the Our Father and before the Lamb of God, just before the reception of Holy Communion. The priest prays that Christ’s peace would remain with the Church and then invites the congregation to offer each other a sign of peace according to local custom. In most places, this involves a handshake, embrace, or bow exchanged with those nearby. Some cultures have developed distinctive ways of sharing peace that reflect local customs and sensibilities. The sign of peace serves multiple purposes in the contemporary Mass, including expressing the unity of the Church, fostering charity among members of the congregation, and preparing hearts to receive Christ in the Eucharist. The gesture reminds Catholics that they cannot truly receive the Lord while harboring unforgiveness or hostility toward others. The sign of peace thus functions as a moment of reconciliation and healing before encountering Christ in Holy Communion.

The restoration of this ancient practice has not been without controversy or confusion, as some Catholics have expressed concern about excessive informality or disruption during this part of the Mass. The Vatican has issued guidelines reminding the faithful that the sign of peace is not merely a social pleasantry but a liturgical act with theological significance. The peace exchanged is specifically the peace of Christ, not generic human friendliness. The gesture should be brief and directed primarily toward those immediately nearby, not an occasion for walking around the church greeting friends or making announcements. Some critics argue that the current placement and execution of the sign of peace detracts from the sacred character of the Mass and interrupts the flow toward Communion. Defenders respond that the sign of peace recovers an important ancient practice and helps worshipers recognize Christ’s presence not only in the Eucharist but also in the community gathered for worship. The ongoing discussion about the sign of peace reveals deeper questions about how Catholics understand the relationship between liturgy and community, between transcendence and immanence, between tradition and renewal. These tensions are not easily resolved, but engaging them thoughtfully can deepen appreciation for the multiple dimensions of Catholic worship.

Variations and Related Symbols

The Pax symbol appears in numerous variations throughout Catholic art, architecture, and devotional objects, each adaptation adding layers of meaning or emphasizing particular aspects of Christian peace. In medieval manuscripts, illuminators often created elaborate versions of the Chi Rho, surrounding it with intricate decorations, figures of saints, or scenes from Christ’s life. The labarum, a military standard adopted by Constantine, combined the Chi Rho with images of the emperor and inscriptions proclaiming victory. This symbol appeared on coins throughout the later Roman Empire and became associated with imperial authority as well as Christian faith. Gothic cathedrals incorporated the Chi Rho into stained glass windows, stone carvings, and metalwork, making it a ubiquitous presence in spaces designed to lift minds toward heaven. Renaissance artists sometimes depicted the Chi Rho in paintings of Constantine’s vision or in scenes of heavenly glory. The symbol thus moved fluidly between different media and contexts, always carrying its basic meaning while taking on additional connotations depending on setting and use. This adaptability helps explain the Chi Rho’s enduring popularity across vastly different historical periods and artistic movements.

The IHS monogram, which represents the name of Jesus in a different way, sometimes appears alongside or in place of the Chi Rho, and the two symbols serve complementary functions. IHS comes from the first three letters of Jesus’s name in Greek, written as ΙΗΣΟΥΣ. Like the Chi Rho, IHS functions as a Christogram that identifies Jesus through abbreviated lettering. The Jesuit order particularly promoted devotion to the Holy Name and made the IHS symbol central to their identity and mission. The Tau cross, a T-shaped cross without the upper vertical extension, became associated with Saint Francis of Assisi and carries connotations of humility and penance. Francis signed his letters with the Tau and saw it as representing Christ’s cross and the Christian’s call to self-denial. The anchor cross combines the shape of an anchor with a cross, symbolizing hope in Christ as the soul’s secure anchor. Early Christians used this symbol in the catacombs because it could pass as a secular image if necessary while simultaneously conveying Christian meaning to those who understood its significance. These various symbols together form a rich visual vocabulary that has allowed Christians to express faith, recognize each other, and adorn sacred spaces for twenty centuries.

Peace as Gift and Task in Christian Life

Catholic theology understands peace as simultaneously a gift that Christ gives and a task that believers must actively pursue. The paradox captures an important truth about Christian existence, which always involves both receiving what God provides and responding with human cooperation. Christ’s peace is gift in the sense that no amount of human effort can create the reconciliation with God that Jesus accomplished through his death and resurrection. Only divine grace can heal the breach caused by sin and restore broken relationship between Creator and creature. Catholics believe they receive this peace through the sacraments, particularly Baptism and Reconciliation, which incorporate believers into Christ’s Body and restore friendship with God when sin has damaged it. Prayer nourishes this peace by keeping believers conscious of God’s presence and dependent on divine assistance. Scripture reading allows God’s word to shape thinking and guide choices. The peace of Christ thus comes from outside the self, an unearned gift that transforms recipients and makes new life possible. This understanding prevents self-righteousness and maintains proper humility about human capacity for goodness.

At the same time, Catholics must actively cultivate and spread the peace they have received, making it a lived reality in relationships, communities, and society. Christ calls his followers to be peacemakers, not merely peace-receivers, and promises blessing to those who take up this vocation. Peacemaking requires concrete actions such as forgiving those who cause harm, seeking reconciliation when relationships break down, working to correct injustice that breeds resentment and violence, and advocating for the vulnerable who lack power to secure their own rights. The Beatitude that blesses peacemakers implies effort and cost, as genuine reconciliation often demands sacrifice from those who pursue it. Catholics are called to imitate Christ who made peace by laying down his life, accepting that peacemaking may require suffering and loss. The Church’s social teaching insists that working for peace includes addressing root causes of conflict such as poverty, inequality, oppression, and disregard for human dignity. Individual gestures of kindness matter but remain insufficient without systemic changes that create conditions for lasting peace. This dual emphasis on gift and task, contemplation and action, receiving and giving, characterizes Catholic spirituality across many domains and finds particular expression in teachings about peace.

The Pax Symbol in Franciscan Tradition

Saint Francis of Assisi and his followers developed a distinctive spirituality of peace that gave special prominence to the greeting “Pax et bonum” and shaped Catholic understanding of peacemaking for centuries. Francis lived during an era of intense violence, when Italian city-states fought constantly, crusades raged in the Holy Land, and heretical movements threatened Church unity. Into this context of conflict, Francis introduced a radically different way of living that rejected violence, embraced poverty, and sought reconciliation across all barriers. His greeting “Peace and all good” expressed his conviction that these two realities belong together, that authentic peace requires goodness and that true goodness produces peace. Francis used this greeting with everyone he encountered, whether fellow Christians, Muslims, animals, or even inanimate creation. His famous peace prayer, though likely composed centuries after his death, captures the spirit of Franciscan peacemaking by asking God to make the pray-er an instrument of peace who brings love where there is hatred, pardon where there is injury, and hope where there is despair. This prayer emphasizes active agency, petitioning not for peace as a passive experience but for transformation into someone who creates peace for others.

Franciscan spirituality connects peace with broader themes of creation care, poverty, humility, and joy that form an integrated vision of Christian life. Francis saw all creatures as siblings united in common origin from God and common destiny to praise the Creator. This conviction led him to treat animals, plants, sun, moon, and even death as brothers and sisters deserving respect and care. His peace extended beyond human relationships to encompass right relationship with all created reality. The voluntary poverty that Francis embraced freed him from the anxiety and acquisitiveness that fuel much human conflict. By owning nothing, Francis needed nothing from others and had nothing to protect, making him unthreatening and open to friendship with all. His humility prevented the pride and self-assertion that poison relationships and communities. His joy testified that peace brings deep satisfaction that worldly pleasures cannot match. Franciscan peace is thus not merely absence of violence but positive flourishing rooted in right relationship with God, neighbor, and creation. The Franciscan movement has continued this emphasis through eight centuries, with organizations like Pax Christi International working for peace through specifically Franciscan-inspired approaches. The tau cross remains the distinctive Franciscan symbol, representing both Christ’s cross and the call to peacemaking that marks authentic discipleship.

Practical Applications for Contemporary Catholics

Understanding the Pax symbol should lead contemporary Catholics to concrete practices that embody Christ’s peace in daily life. First, Catholics can cultivate personal peace through regular prayer, sacramental participation, and spiritual reading that keep them rooted in God’s love and responsive to divine grace. The examination of conscience helps identify areas where anxiety, anger, or resentment disturb interior peace and need to be brought to God in confession or prayer. Meditation and contemplative practices train the mind to rest in God’s presence rather than constantly churning with worry about circumstances. Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus can remind Catholics that Christ’s heart burns with love for humanity and desires to share that love with all who approach him. These personal practices form the foundation for becoming people of peace who can extend to others what they have received from God. Without interior peace, attempts at external peacemaking ring hollow and lack spiritual power.

Second, Catholics should examine their relationships and communities to identify where reconciliation is needed and possible. This might involve initiating difficult conversations with estranged family members, forgiving old hurts that continue to fester, or apologizing for wrongs committed. In parishes, fostering peace might mean bridging divides between different groups, welcoming newcomers, or working to resolve conflicts that disturb community harmony. Catholics can support organizations working for peace at local, national, and international levels, lending their voices and resources to efforts that address root causes of violence. Advocacy for policies that promote justice, protect human rights, and create conditions for peaceful coexistence fulfills the Church’s call to work for the common good. Teaching children about peace through word and example forms the next generation’s capacity for reconciliation and nonviolence. Choosing to consume media that builds up rather than tears down, that promotes understanding rather than division, that highlights hope rather than fear, shapes individual and collective consciousness toward peace. Each small choice to respond to hostility with love, to prejudice with openness, to violence with nonviolence plants seeds that can grow into lasting transformation. The Pax symbol thus becomes not merely historical artifact or decorative element but summons to lived discipleship that makes Christ’s peace visible and tangible in the world.

Common Misunderstandings About the Pax Symbol

Several common misunderstandings cloud contemporary perception of the Pax symbol and its meaning within Catholic tradition. Some people assume the Chi Rho symbol or the term “pax” originated as secret codes that early Christians used exclusively to hide their identity during persecution. While Christians did use these symbols discretely during dangerous periods, they were not invented for concealment and had broader purposes in expressing faith and adorning worship spaces. The Chi Rho particularly became more prominent after Constantine’s conversion, when Christianity gained imperial favor and moved from margins to center of Roman society. Another misconception treats all Christian peace symbols as essentially equivalent, failing to recognize the distinct meanings and historical contexts of different images and practices. The Chi Rho, the pax board, the Franciscan tau cross, and the contemporary sign of peace all relate to Christ’s peace but function differently and carry particular emphases. Conflating them produces confusion about Catholic tradition and obscures the rich development of peace theology over two millennia. Catholics benefit from understanding these distinctions and appreciating how different expressions of peace have served the Church in various circumstances.

Some contemporary Catholics assume the sign of peace in Mass is optional or merely a social nicety that can be skipped without significance. This misunderstanding fails to grasp the liturgical and theological importance of this gesture as expression of ecclesial unity and preparation for Communion. While the specific form varies by culture and individuals may have legitimate reasons for minimal participation, the sign of peace itself belongs to the structure of the Mass and serves essential purposes. Others mistakenly believe that Christian peace means passive acceptance of injustice or refusal to resist evil. Catholic teaching clearly distinguishes peace from pacifism understood as absolute nonresistance, recognizing legitimate self-defense while still preferring nonviolent means whenever possible. The peace Christ brings includes active opposition to sin and work to establish justice, not merely avoiding conflict. Some people also reduce Christian peace to emotional tranquility or individual inner calm, missing the social and cosmic dimensions emphasized in Scripture and tradition. While personal peace matters, the biblical shalom and the Catechism’s definition encompass much more than private religious experience. Peace in Catholic understanding necessarily involves right relationships, just structures, and harmonious communities, not merely individual psychological states. Correcting these misunderstandings allows Catholics to embrace more fully the rich tradition of peace that the Pax symbol represents.

The Pax Symbol in Contemporary Devotional Practice

Modern Catholics can incorporate the Pax symbol into personal devotion and communal prayer in ways that deepen spiritual life and strengthen commitment to peacemaking. Wearing jewelry or displaying art featuring the Chi Rho serves as visible reminder of Christ’s peace and witness to others of Christian identity. Religious goods stores offer medals, crucifixes, wall plaques, and other items decorated with the symbol that can sanctify homes and personal spaces. Using the traditional greeting “Pax” or “Peace be with you” when encountering other Catholics creates bonds of unity and recalls the Church’s ancient customs. Some Catholics adopt the Franciscan “Pax et bonum” as their characteristic greeting, particularly if they belong to Franciscan third orders or have special devotion to Saint Francis. Including prayers for peace in daily devotions directs attention to this crucial dimension of Christian vocation and aligns personal prayer with the Church’s constant intercession for peace. The rosary offers opportunity to meditate on Christ’s peace while praying the Joyful Mystery of the Nativity, when angels proclaimed peace on earth, or the Glorious Mystery of the Resurrection, when Christ greeted disciples with peace. Chaplets specifically dedicated to peace exist and provide structured formats for sustained prayer.

Parishes can emphasize the Pax symbol and peace theme through liturgical environment, educational programs, and service opportunities. Banners featuring the Chi Rho or other peace symbols can adorn worship spaces, particularly during seasons when peace receives special emphasis such as Advent or the January Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. Homilies can explore biblical and theological dimensions of Christian peace, helping parishioners understand the depth of Catholic teaching on this topic. Adult education offerings might examine the history of Christian peace symbols, the development of Catholic social teaching on war and peace, or practical skills for conflict resolution and reconciliation. Youth programs can introduce young people to peacemaking through service projects, discussions of social justice, and formation in nonviolent communication. Parishes might partner with Catholic peace organizations to host speakers, sponsor advocacy campaigns, or organize pilgrimages to sites significant in peace history. Displaying images of Catholic peacemakers such as Saint Francis, Saint Martin de Porres, Dorothy Day, or Oscar Romero reminds the community that peace requires courage and sometimes martyrdom. By making peace prominent in multiple aspects of parish life, communities form members who understand their identity as peacemakers and take seriously the call to work for reconciliation and justice. The Pax symbol thus becomes living reality rather than mere historical curiosity, shaping contemporary discipleship as it has for twenty centuries.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.