Brief Overview

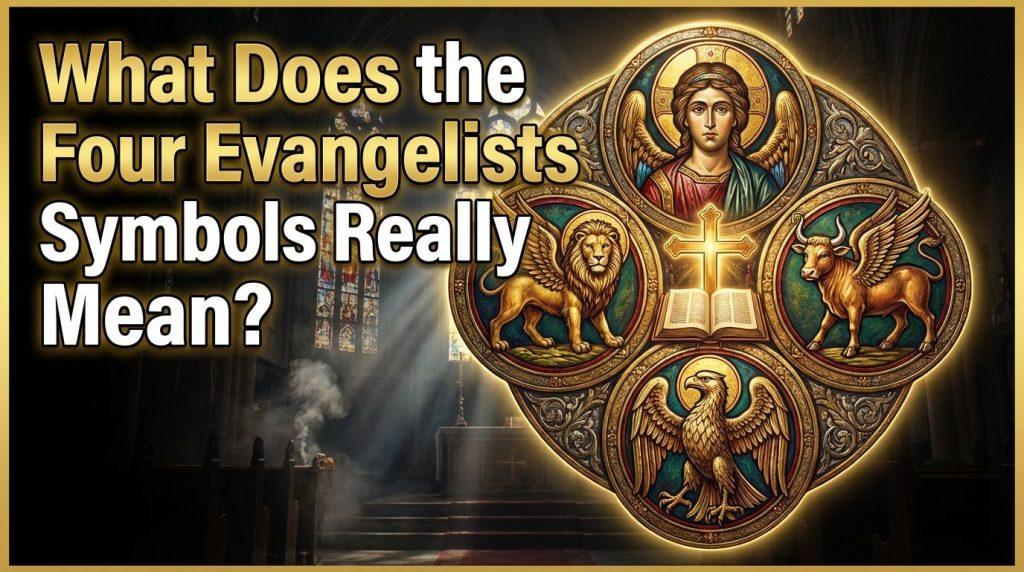

- The four symbols of the evangelists are a winged man for Matthew, a lion for Mark, an ox for Luke, and an eagle for John.

- These symbols originate from the prophetic visions of four living creatures described in the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelation.

- Saint Irenaeus of Lyons was the first Church Father to systematically connect these four living creatures to the four Gospel writers in the second century.

- Each symbol reflects the distinctive theological emphasis and opening passages of its corresponding Gospel.

- The symbols represent different aspects of Christ’s nature and mission as portrayed by each evangelist.

- Catholic tradition views these four Gospels as complementary portraits that together provide a complete picture of Jesus Christ.

The Biblical Foundation of the Symbols

The symbols of the four evangelists find their roots deep within Sacred Scripture itself, particularly in two major prophetic visions that span both the Old and New Testaments. The prophet Ezekiel, writing during the Babylonian exile around 593 BC, records an extraordinary vision of God’s glory in which he encounters four mysterious living creatures. These beings possessed four faces each, representing a human, a lion, an ox, and an eagle, as described in Ezekiel 1:5-10. The creatures served as throne bearers for the divine presence and moved in perfect harmony with the Spirit of God. Their appearance combined human and animal features in ways that defied ordinary description, yet Ezekiel’s detailed account provided future generations with powerful imagery that would shape Christian understanding of the Gospels. The vision occurred by the river Chebar and marked the beginning of Ezekiel’s prophetic ministry to the exiled people of Israel. Each face on the creatures represented different qualities and characteristics that would later be understood to correspond to the nature of Christ as revealed in the four Gospels. The human face symbolized intelligence and reason, the lion represented strength and royalty, the ox signified patient service and sacrifice, and the eagle embodied swiftness and divine transcendence. These four faces were not random selections but rather represented the noblest and most powerful creatures in their respective categories among God’s creation.

The New Testament book of Revelation provides a complementary vision of four living creatures surrounding the throne of God in heaven. Saint John the Evangelist, writing from the island of Patmos around 95 AD, describes seeing four living beings that resembled a lion, an ox, a man, and an eagle in flight, as recorded in Revelation 4:6-8. These creatures were covered with eyes both inside and outside, symbolizing their perfect knowledge and vigilance. They ceaselessly proclaimed the holiness of God, crying out day and night, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty, who was, and who is, and who is to come.” Unlike Ezekiel’s vision where each creature had four faces, John’s vision presents four distinct creatures, each with its own form. This difference in presentation does not represent a contradiction but rather shows how divine mysteries can be revealed through various images and symbols. The placement of these creatures around God’s throne emphasizes their closeness to divine majesty and their role as witnesses to God’s glory. Their continuous worship serves as a model for the Church’s own liturgical prayer. The connection between Ezekiel’s ancient vision and John’s apocalyptic revelation demonstrates the continuity of God’s self-disclosure throughout salvation history. Both visions reveal aspects of heavenly worship and divine glory that transcend ordinary human experience and language.

The Early Church’s Interpretation

Saint Irenaeus of Lyons, writing in the late second century in his work “Against Heresies,” became the first major Church Father to explicitly connect the four living creatures with the four evangelists. His interpretation arose during a time when the Church needed to defend the authenticity of the four canonical Gospels against competing texts and heretical teachings. Irenaeus argued that just as there are four regions of the world and four principal winds, it was fitting that the Church should have exactly four Gospels. He understood the four living creatures as prophetic symbols that God had revealed long before the Gospels were written, confirming divine providence in the composition of the New Testament canon. Irenaeus associated the human figure with Matthew because that Gospel emphasizes Christ’s human genealogy and incarnation. He connected the lion with John, seeing in it a symbol of Christ’s royal power and the confident, majestic opening of John’s Gospel. The ox he attributed to Luke, recognizing the priestly and sacrificial themes that pervade that Gospel. Finally, he associated the eagle with Mark, interpreting it as representing the prophetic spirit that descends from above. While later tradition would adjust some of these specific associations, Irenaeus established the fundamental principle that the four creatures and four Gospels were divinely connected.

Saint Jerome, the great biblical scholar and translator of the Latin Vulgate, refined the symbolism in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. His interpretation, drawing on both Scripture and pastoral insight, became the standard understanding that the Catholic Church has maintained through the centuries. Jerome connected Matthew with the winged man or angel because Matthew’s Gospel begins with the human genealogy of Jesus, tracing His ancestry through Joseph back to Abraham and demonstrating His full humanity. The emphasis on Christ’s incarnation and His entry into human history through a specific family line made the human figure the most appropriate symbol. Jerome associated Mark with the lion based on how Mark’s Gospel opens with John the Baptist crying out in the wilderness, a voice powerful and solitary like a lion’s roar in the desert. The lion also represented Christ’s royal dignity and power, themes that Mark emphasizes throughout his narrative. For Luke, Jerome selected the ox or calf because Luke begins his Gospel in the Temple with the priest Zechariah offering sacrifice. The ox was the primary sacrificial animal in Jewish temple worship, making it a fitting symbol for a Gospel that emphasizes Christ’s priestly office and His sacrifice for human salvation. Jerome assigned the eagle to John because that Gospel soars to the highest theological heights, beginning with the pre-existence of the Word with God before creation. The eagle, which flies higher than any other bird and was believed in ancient times to look directly at the sun, perfectly represented John’s penetrating insight into divine mysteries.

Matthew and the Winged Man

The Gospel of Matthew opens with a detailed genealogy of Jesus Christ, beginning with the words found in Matthew 1:1, “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.” This human lineage establishes Jesus’ credentials as the promised Messiah from the line of King David and connects Him to the covenant God made with Abraham. The genealogy traces Jesus’ ancestry through forty-two generations, organized into three sets of fourteen generations each. This careful human accounting demonstrates that Jesus entered history as a real man born into a specific family at a particular time and place. The evangelist presents Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies concerning the Messiah who would come from David’s royal line. Matthew’s Gospel consistently emphasizes Christ’s humanity and His role as the new Moses who gives the new law of the kingdom of heaven. The Sermon on the Mount, unique to Matthew’s Gospel, presents Jesus as the divine teacher who speaks with authority to instruct humanity in the ways of righteousness. Throughout the Gospel, Matthew highlights Jesus’ compassion for human suffering, His ministry to the lost sheep of the house of Israel, and His concern for proper interpretation of the law. The human figure or angel as Matthew’s symbol reflects this consistent focus on Christ’s true humanity and His mission to save the human race.

The winged aspect of Matthew’s symbol, depicting either a winged man or an angel, adds a layer of meaning that points to the divine dimension of Christ’s human nature. While Matthew emphasizes Jesus’ humanity, he never separates it from His divinity. The wings suggest that this is no ordinary human but rather one whose humanity is united with divine nature. The opening chapters of Matthew’s Gospel contain the infancy narratives where angels play prominent roles, appearing to Joseph in dreams to guide the holy family’s actions. An angel announces to Joseph that Mary has conceived by the Holy Spirit, instructing him not to fear taking her as his wife. Angels warn the family to flee to Egypt to escape Herod’s murderous plot and later direct their return to Nazareth. This angelic presence throughout the early chapters reinforces the appropriateness of the winged human figure as Matthew’s symbol. The Gospel presents Jesus as both fully human, sharing in all aspects of human life except sin, and fully divine, possessing authority over nature, demons, sickness, and even death. Matthew records Jesus’ claim to have authority on earth to forgive sins, something only God can do. The genealogy itself contains miraculous elements, mentioning women whose stories involved divine intervention in unexpected ways. The symbol of the winged man thus captures the essential mystery of the Incarnation that Matthew proclaims—that God has become man without ceasing to be God.

Mark and the Lion

The Gospel of Mark begins with a bold proclamation followed by a prophetic quotation, opening with the words of Mark 1:1-3, “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. As it is written in Isaiah the prophet: Behold, I send my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way, the voice of one crying out in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.” This dramatic opening immediately thrusts readers into the public ministry of Jesus without any genealogy or infancy narrative. The reference to a voice crying in the wilderness evokes the image of a powerful, solitary roar that commands attention across an empty landscape. The lion’s roar serves as a fitting metaphor for John the Baptist’s prophetic ministry, calling people to repentance and preparing them for the coming of the Messiah. Lions were known throughout the ancient world as symbols of strength, courage, majesty, and royal authority. The lion was particularly associated with the tribe of Judah, from which the Messiah was prophesied to come, as indicated in Genesis 49:9, where Jacob describes Judah as “a lion’s cub.” Mark’s Gospel consistently portrays Jesus with regal authority and power, showing Him as the mighty Son of God who commands demons, calms storms, heals the sick, and speaks with unquestionable authority.

Mark’s narrative moves with swift intensity, frequently using the word “immediately” to convey the rapid pace of Jesus’ ministry and the urgency of His mission. This sense of decisive action and power mirrors the characteristics of a lion, which strikes swiftly and dominates its territory. The Gospel emphasizes Jesus’ authority over all creation, showing Him exercising divine prerogatives that belong to God alone. When Jesus calms the storm with a simple command in Mark 4:39, “Peace! Be still,” the disciples respond with awe-filled questions about His identity, asking who this could be that even wind and sea obey Him. The demon-possessed man in Mark 5:1-20 recognizes Jesus immediately as “Son of the Most High God” and the demons plead for mercy before His commanding presence. Throughout Mark’s Gospel, Jesus demonstrates the authority of a king who has come to reclaim His kingdom from the forces of evil. The healing miracles are not presented merely as acts of compassion but as demonstrations of divine power that prove Jesus’ identity as the mighty Son of God. Even Jesus’ teaching is noted for its authoritative character, as Mark records in Mark 1:22 that “the people were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority, and not as the scribes.” The lion symbol perfectly captures this portrait of Christ as the powerful, majestic King who exercises sovereign authority over all creation and announces the breaking in of God’s kingdom.

Luke and the Ox

The Gospel of Luke opens not with Jesus or John the Baptist but with a temple priest named Zechariah who was chosen by lot to offer incense in the sanctuary of the Lord. This priestly context for Luke’s beginning provides the foundation for the ox or calf as his symbol, since these animals were the primary sacrificial offerings in Jewish worship. Luke 1:5-9 establishes the setting in the temple during a moment of liturgical service when an angel appears to announce the birth of John the Baptist. The ox was particularly associated with patient labor and with priestly sacrifice, making it an apt symbol for a Gospel that emphasizes both Christ’s sacrificial death and His patient ministry to outcasts and sinners. The ox represented strength harnessed for service rather than conquest, power directed toward burden-bearing rather than domination. In the Old Testament law, oxen were used for pulling plows and threshing grain, images of patient, sustained work that produces life-giving food. They were also the primary animals offered in the most solemn sacrifices, particularly on the Day of Atonement when bulls were slain to atone for the sins of the high priest and the people. Luke’s Gospel presents Jesus as the ultimate High Priest whose self-sacrifice accomplishes what animal sacrifices could only symbolize—true atonement for human sin and reconciliation between God and humanity.

Luke emphasizes Jesus’ compassion and mercy more than any other Gospel, showing Him consistently reaching out to the marginalized, the poor, women, tax collectors, sinners, and Gentiles. The parables unique to Luke, such as the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:25-37 and the Prodigal Son in Luke 15:11-32, highlight divine mercy and the joy of reconciliation. The story of Zacchaeus the tax collector in Luke 19:1-10 demonstrates Jesus’ mission to seek and save the lost. The account of the repentant criminal crucified alongside Jesus in Luke 23:39-43 shows mercy extended even at the moment of death. These narratives reveal a consistent theme of sacrificial love that gives itself for others without counting the cost. The ox that labors patiently in the field and is ultimately offered on the altar represents this willingness to serve and to be consumed for the benefit of others. Luke’s account of the Last Supper in Luke 22:14-20 emphasizes the sacrificial nature of Jesus’ death, presenting it as the new covenant sealed in His blood. The Gospel also uniquely records Jesus’ prayer on the cross, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do,” showing sacrificial love extended even to those who perpetrate evil. The ox symbol thus captures Luke’s portrait of Christ as the patient servant and ultimate sacrifice whose self-giving love accomplishes human redemption.

John and the Eagle

The Gospel of John begins with the most theologically profound prologue in all of Scripture, declaring in John 1:1-3, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.” This majestic opening soars immediately to the heights of divine mystery, transcending time and earthly concerns to contemplate the eternal relationship between the Father and the Son. No other Gospel begins at such a lofty altitude of theological reflection. The eagle, which flies higher than any other bird and was traditionally believed capable of gazing directly at the sun without being blinded, serves as the perfect symbol for John’s soaring theological vision. Eagles were known for their keen sight, able to spot prey from great distances while flying at tremendous heights. This combination of altitude and clarity of vision makes the eagle an ideal representation of John’s Gospel, which penetrates most deeply into the mystery of Christ’s divinity while maintaining perfect clarity about His identity and mission.

John’s Gospel is structured around a series of “I am” statements where Jesus reveals His divine identity using the sacred name of God revealed to Moses in Exodus 3:14. Jesus declares “I am the bread of life” in John 6:35, “I am the light of the world” in John 8:12, “I am the good shepherd” in John 10:11, “I am the resurrection and the life” in John 11:25, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life” in John 14:6, and “I am the true vine” in John 15:1. These declarations reveal aspects of Christ’s nature and work that transcend ordinary human categories. The extended discourses in John’s Gospel, such as the conversation with Nicodemus about being born again in John 3:1-21, the dialogue with the Samaritan woman about living water in John 4:1-42, and the lengthy farewell discourse in John 14-17, plumb depths of spiritual truth that the other Gospels touch on only briefly. John emphasizes the pre-existence of Christ, His perfect unity with the Father, and His role in creation. The Gospel presents Jesus as the divine Word made flesh who reveals the Father to humanity. The high priestly prayer of Jesus in John 17 reveals the eternal relationship between Father and Son and Jesus’ mission to bring believers into that relationship. The eagle symbol represents this capacity to rise above earthly perspectives and contemplate divine realities while maintaining the clarity of vision necessary to communicate these mysteries to believers on earth.

The Theological Significance of Four Gospels

The Catholic Church has always maintained that the existence of four distinct Gospels rather than a single harmonized account serves an essential theological purpose in revealing the fullness of Christ’s identity and mission. Each Gospel presents a particular aspect or emphasis that contributes to a complete portrait of Jesus Christ. The Catechism notes that the Church recognizes these four Gospels as divinely inspired witnesses to the one Gospel of Jesus Christ. No single human author or perspective could adequately capture the inexhaustible mystery of God made man. The variety within the Gospels demonstrates that divine truth can be expressed through different literary styles, theological emphases, and pastoral concerns without contradiction. Matthew writes primarily for a Jewish Christian audience, showing how Jesus fulfills Old Testament prophecy and establishes the Church as the new Israel. Mark addresses believers facing persecution, presenting Jesus as the suffering servant who calls His followers to take up their crosses. Luke writes for Gentile converts, emphasizing God’s universal mercy and the inclusion of all people in salvation. John writes for mature believers, helping them contemplate the profound mysteries of Christ’s divinity and His relationship with the Father.

The four evangelists together provide what later theologians would call a “complementary” rather than “contradictory” diversity in their presentations of Jesus. They differ in the events they choose to highlight, the order in which they present material, the particular sayings of Jesus they record, and the theological themes they emphasize, yet these differences enrich rather than undermine the witness of faith. When the gospels are read together, apparent tensions or differences often illuminate different aspects of the same truth. For instance, Matthew and Luke both record Jesus’ birth but with different details and emphases that together provide a fuller picture than either account alone. The different resurrection narratives complement each other to give a more complete testimony to that central event of Christian faith. The Church’s preservation of four distinct Gospels rather than producing a single harmonized version reflects her confidence that truth can sustain diversity of expression. The symbols of the four evangelists visually represent this theological principle—the man, lion, ox, and eagle are all different creatures yet all surround the throne of God in perfect harmony, each contributing its unique nature to the worship of the divine majesty.

Historical Development of the Symbols in Christian Art

The symbols of the four evangelists became a staple of Christian iconography from the early medieval period onward, appearing in illuminated manuscripts, sculpture, stained glass, and architectural decoration throughout churches in both East and West. The earliest surviving artistic representations date from the fourth and fifth centuries, appearing in manuscripts and catacomb frescoes. The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel manuscript created by Celtic monks around 800 AD, contains elaborate depictions of the four evangelist symbols rendered in intricate patterns and vibrant colors. Medieval churches frequently featured the four creatures in sculptural programs around doorways or in capitals of columns, serving as visual reminders of the Gospel message proclaimed within. The creatures typically appear with wings, even though only the human figure and eagle explicitly have wings in the biblical texts, as a way of indicating their heavenly origin and their role as messengers of divine truth. The tetramorph, as the composite representation is called, sometimes appears as four separate figures arranged around a central image of Christ in majesty, and sometimes as a single composite creature with four faces, more closely following Ezekiel’s original vision.

Renaissance and Baroque artists continued the tradition while adapting it to new artistic styles and theological emphases of their periods. The four symbols might appear in paintings as small figures in corners, accompanying larger scenes from the life of Christ or images of the evangelists themselves at work writing their Gospels. Many churches commissioned sets of statues or paintings showing each evangelist with his symbolic creature as a companion. These representations served educational purposes in ages when most Christians could not read, providing visual catechesis about the Gospel message. The symbols helped worshipers remember which Gospel reading was being proclaimed during liturgy. The placement of evangelist symbols near the four corners or sides of church buildings reminded congregations that the Gospel must be preached to the four corners of the earth. In Catholic liturgy, the four creatures came to represent not only the evangelists but also the fourfold action of the Mass, the four cardinal virtues, and various other quaternities in Christian theology. The enduring presence of these symbols in Christian art demonstrates their effectiveness as visual theology, conveying deep truths about Scripture and salvation in forms that transcend cultural and linguistic barriers.

The Wings and Their Meaning

The tradition of depicting Matthew’s human figure, Luke’s ox, and Mark’s lion with wings requires explanation since the biblical texts themselves only explicitly describe wings on the eagle representing John. This artistic convention developed to harmonize the imagery from Ezekiel’s vision, where all four faces belong to winged creatures, with John’s Revelation vision, where the four separate creatures each have wings. The wings serve several symbolic purposes beyond merely following the biblical descriptions. First, they indicate that these symbols represent heavenly realities rather than earthly animals or persons. The wings designate the evangelists as messengers who bring divine revelation from heaven to earth. Just as angels in Scripture almost invariably appear with wings to indicate their role as heavenly messengers, the winged symbols of the evangelists show that these writers communicated not their own human wisdom but the Gospel message revealed by God. The wings also symbolize the supernatural inspiration of Scripture itself—the human authors wrote under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, who lifted their minds and hearts to perceive and communicate divine truth.

The wings further represent the transcendent nature of the Gospel message itself, which originates in heaven and descends to earth through the incarnation of Christ and the preaching of the Church. The winged creatures that surround God’s throne in the book of Revelation engage in ceaseless worship, and their wings enable them to fly between heaven and earth as agents of divine will. The evangelists, by recording the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, became instruments through which God’s salvific purpose was communicated to all generations. Their writings have enabled the Gospel to “fly” across centuries and continents, reaching people in every age and culture. The four Gospels together proclaim the one Gospel with power to transform human hearts and draw people to faith in Christ. The wings on all four symbols emphasize that while the evangelists were real human persons writing in specific historical contexts for particular communities, their work transcended those limitations to become the inspired Word of God for the universal Church. The Holy Spirit, often depicted in Christian art as a dove with wings, empowered the evangelists to write accounts that would serve the Church in every time and place.

The Symbols in Catholic Liturgy and Devotion

The symbols of the four evangelists maintain active presence in Catholic liturgical life and devotional practice rather than serving merely as historical artifacts or artistic decorations. During the proclamation of the Gospel at Mass, the Book of the Gospels is carried in procession with candles and incense, honors that recognize Christ’s real presence in the sacred text. The four evangelists are venerated as saints, each with designated feast days in the liturgical calendar. Matthew’s feast is celebrated on September 21, Mark’s on April 25, Luke’s on October 18, and John’s on December 27. These feasts give Catholics opportunity to reflect on the particular gifts each evangelist brought to proclaiming the Gospel. Churches often display the evangelist symbols near the ambo or lectern from which Scripture is proclaimed, reminding the faithful that they are hearing the inspired word recorded by these four witnesses. Stained glass windows frequently feature the symbols, allowing natural light to illuminate them as a reminder that the Gospel brings divine light into the darkness of human ignorance and sin.

Catholic devotional traditions have incorporated the evangelist symbols in various ways to deepen appreciation for Scripture. Religious art for homes often includes depictions of the four creatures as reminders to read and meditate on the Gospels regularly. Some prayer traditions encourage reading one Gospel per day of the week, cycling through the four in succession to encounter Christ from different perspectives. Retreats and study programs organized around the four Gospels use the symbols as organizing principles to help participants understand the distinctive characteristics of each account. The symbols appear in liturgical art on altar cloths, vestments, and sacred vessels, integrating the Gospel message into the material elements of worship. Catholic schools and religious education programs use the symbols as teaching tools to help students remember the key features of each Gospel and recognize that Scripture contains diversity within unity. The enduring presence of these symbols in Catholic life demonstrates the Church’s commitment to making Scripture accessible and meaningful to believers in every generation through visual and symbolic language that transcends barriers of literacy and culture.

Understanding Unity in Diversity

The four evangelist symbols teach a crucial lesson about how the Catholic Church understands divine revelation and biblical interpretation. The existence of four distinct Gospel accounts with different emphases, styles, and selections of material does not represent confusion or contradiction but rather reflects the richness of truth that cannot be captured by a single perspective. God accommodated human limitations by providing multiple witnesses to the life and teaching of Jesus Christ, each highlighting aspects that resonate with different audiences and address different questions about faith. The man, lion, ox, and eagle are very different creatures with distinct characteristics and capabilities, yet all can validly represent aspects of the one Christ because His identity and mission encompass all that these symbols represent. He is fully human like the man, exercising authority like the lion, offering sacrifice like the ox, and possessing divine wisdom like the eagle that soars to heaven. The symbols together proclaim the mystery of the Incarnation—God has become man without ceasing to be God, and this person Jesus Christ can only be adequately presented through multiple complementary perspectives.

This principle of unity in diversity extends beyond the four Gospels to the entire structure of Catholic theology and practice. The Church recognizes that truth is sufficiently rich and complex that it requires varied expressions to be fully communicated. Different theological traditions within Catholicism, represented by various religious orders and schools of thought, emphasize different aspects of the faith without contradicting each other. Different forms of liturgy, such as the Roman Rite, Byzantine Rite, and other Eastern Catholic liturgies, express the same faith through diverse ceremonial forms. Different saints and spiritual writers present different paths to holiness that all lead to union with God. The evangelist symbols visually represent this Catholic conviction that legitimate diversity exists within essential unity. All four creatures surround the one throne and worship the one God. All four evangelists proclaim the one Gospel of Jesus Christ. Their differences serve the truth rather than undermining it, just as light passing through a prism produces many colors while remaining fundamentally one reality. Catholics are called to appreciate this diversity as a gift rather than seeing it as a problem requiring resolution.

Practical Applications for Catholic Life

Understanding the symbols of the four evangelists provides Catholics with practical guidance for engaging with Scripture more deeply and fruitfully. When reading or hearing Matthew’s Gospel, believers can consciously reflect on Christ’s humanity and His teaching ministry, considering how the incarnation demonstrates God’s solidarity with human experience. Matthew’s emphasis on Jesus as the new Moses and teacher of righteousness calls Catholics to serious study of Christ’s moral teachings and their application to daily life. When encountering Mark’s Gospel, readers can focus on Christ’s power and authority, finding courage for their own struggles against evil and confidence in Jesus’ ability to deliver them from whatever threatens their faith. Mark’s swift narrative style and emphasis on discipleship challenges Catholics to respond promptly and decisively to Christ’s call. Luke’s Gospel invites meditation on God’s mercy and compassion, encouraging believers to examine their own capacity for forgiveness and care for the marginalized. Luke’s particular attention to women, the poor, and outcasts reminds Catholic communities to embody the same inclusive love that Jesus demonstrated. John’s Gospel calls believers to contemplative prayer and theological reflection, moving beyond surface understanding to penetrate the deep mysteries of faith. John’s emphasis on love as the essential Christian virtue guides Catholics in evaluating their spiritual progress.

The symbols also remind Catholics that a complete spiritual life requires balance among different emphases rather than exclusive focus on any single aspect of Christian truth. A healthy Catholic spirituality will include attention to Christ’s humanity and divinity, will recognize both His kingly authority and His sacrificial service, will value both theological study and practical charity, will maintain both contemplative prayer and active ministry. The four creatures surrounding God’s throne in perfect harmony model how these diverse emphases should coexist in Catholic life without competition or conflict. Personal prayer can incorporate reflection on the evangelist symbols as a way of examining which aspects of Christian life might be neglected or overemphasized. Parishes and communities can use the symbols to evaluate whether their ministries and activities reflect the full breadth of the Gospel or focus too narrowly on particular concerns. The symbols provide a framework for understanding that different seasons of life and different vocations within the Church will naturally emphasize different Gospel values, yet all contribute to the single mission of proclaiming Christ and making disciples. Catholic educators can use the symbols to help students appreciate Scripture’s literary diversity and theological richness rather than being confused by apparent differences among the Gospels.

The Symbols and Catholic Understanding of Scripture

The Catholic Church’s approach to Sacred Scripture finds clear expression in how the tradition has understood and used the symbols of the four evangelists. The Church recognizes Scripture as both human and divine, written by human authors using their own literary styles and cultural contexts while simultaneously being inspired by the Holy Spirit to communicate divine truth without error. The four evangelists were real historical persons with individual personalities, backgrounds, and pastoral concerns that shaped how they presented the Gospel message. Matthew wrote as a Jewish Christian deeply versed in Old Testament Scripture who wanted to help his community understand how Jesus fulfilled ancient prophecies. Mark wrote a fast-paced narrative suitable for oral proclamation that emphasized Jesus’ powerful actions over lengthy discourses. Luke conducted historical research and composed an orderly account for Gentile believers unfamiliar with Jewish customs. John wrote later in the first century for Christians who needed deeper theological instruction to strengthen their faith. These human dimensions of Gospel composition are not problems to be explained away but rather aspects of how God chose to communicate divine truth through human instruments.

The symbols capture this dual nature of Scripture by combining earthly creatures with heavenly wings. The man, lion, ox, and eagle are all earthly animals that any reader could recognize and understand, yet their wings indicate participation in heavenly realities. Similarly, the Gospels are truly human documents that reflect their authors’ contexts and concerns, yet they communicate divine revelation that transcends those particular circumstances. Catholic biblical interpretation seeks to understand both dimensions rather than reducing Scripture to merely human literature or treating it as divine dictation that ignores human authorship. The Church reads Scripture within the living Tradition that has received and interpreted these texts for two millennia, recognizing that the Holy Spirit guides the Church’s understanding of the inspired texts. The symbols of the evangelists remind Catholics that Scripture comes to us through the mediation of particular human witnesses whom God chose and inspired for this task. Devotion to the evangelists as saints connects love for Scripture with appreciation for the human persons through whom divine revelation was transmitted. This Catholic understanding avoids the errors of fundamentalism that ignores the human dimension of Scripture and modernist skepticism that denies its divine inspiration.

The Symbols in Ecumenical Perspective

The symbols of the four evangelists represent one area of Christian heritage that unites Catholics with other Christian traditions rather than dividing them. Orthodox Christians, Anglicans, Lutherans, and many other Protestant communities recognize and use the same symbols with the same associations—Matthew with the winged man, Mark with the lion, Luke with the ox, and John with the eagle. This shared iconographic tradition reflects the common reverence all Christians have for the four canonical Gospels as authoritative witnesses to Jesus Christ. Churches across denominational lines display the evangelist symbols in art and architecture, demonstrating a unity in how Christians visualize and honor Scripture. The symbols appear in Orthodox iconography with the same meanings they have in Western Catholic art. Protestant churches that use minimal decoration often retain evangelist symbols even when other traditional imagery is removed. This widespread acceptance across Christian traditions testifies to the deep biblical roots of the symbols and their effectiveness in communicating Gospel truths.

Studying the evangelist symbols provides opportunities for ecumenical dialogue and shared learning among Christians of different traditions. Catholics and Protestants can discuss together how each Gospel presents Christ while learning from different interpretive traditions that have developed in their communities. Orthodox and Catholic Christians can share insights from their respective artistic and liturgical traditions that use the symbols. Bible studies that focus on the distinctive characteristics of each Gospel, organized around the evangelist symbols, can bring together Christians from various backgrounds in common reflection on Scripture. The symbols remind all Christians that they share the foundational texts of their faith even where they differ in theological interpretation or church structure. Ecumenical worship services often feature the evangelist symbols as neutral ground that all participants can affirm. The growing movement toward increased Bible reading among Catholics in recent decades has created new opportunities for fruitful exchange with Protestant brothers and sisters who have a long tradition of serious Scripture study. The evangelist symbols serve as a meeting point where Christians of different traditions can recognize their fundamental unity in Christ while respecting the diverse ways they have received and interpreted the one Gospel message.

Conclusion and Contemporary Relevance

The symbols of the four evangelists, rooted in biblical vision and developed through centuries of Christian tradition, remain relevant and meaningful for Catholics today. In an age of information overload and competing narratives, these ancient symbols offer a framework for understanding how diverse perspectives can together communicate truth rather than producing confusion. The four creatures surrounding God’s throne model how the Catholic Church can embrace legitimate diversity while maintaining essential unity. The symbols remind modern believers that Scripture is not a monolithic text but a library of inspired writings that requires careful, prayerful reading to understand properly. As Catholics engage with a pluralistic world containing many voices and viewpoints, the evangelist symbols teach that truth is robust enough to sustain different approaches and emphases without fragmenting into relativism. The harmony of the four Gospels demonstrates that authentic diversity serves rather than threatens unity when all perspectives remain focused on Christ as the center.

The symbols continue to inspire Catholic art, architecture, and devotional practice, connecting contemporary believers with the long tradition of the Church. New artistic interpretations of the evangelist symbols in modern styles demonstrate their continuing vitality and adaptability to changing cultural contexts. The symbols appear in contemporary Catholic churches built with modern materials and designs, showing that ancient truths can find authentic expression in new forms. Digital media and online resources have made the evangelist symbols accessible to wider audiences than ever before, allowing Catholics worldwide to encounter these traditional images and learn their meanings. Youth ministry programs use the symbols as engaging visual tools for teaching about the Gospels, finding that images transcend generational barriers in communication. The enduring power of the evangelist symbols lies in their ability to convey profound theological truths through simple, memorable images that speak to human imagination and touch the heart as well as the mind. As Catholics continue to proclaim the Gospel in the twenty-first century, these ancient symbols remind them that they participate in an unbroken tradition stretching back to the apostolic age, a tradition that remains fresh and life-giving for every generation.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.