Brief Overview

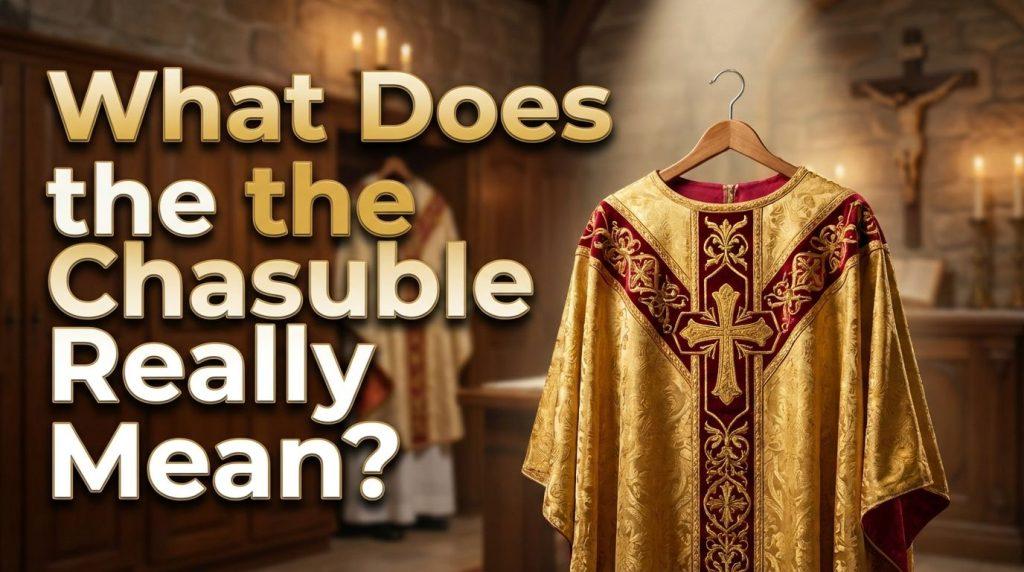

- The chasuble is the outer liturgical vestment worn by priests during Mass, symbolizing charity and the yoke of Christ that priests bear in serving God’s people.

- This garment developed from a common Roman outdoor cloak called the paenula, which evolved over centuries into a distinctively Christian liturgical vestment.

- The word “chasuble” derives from the Latin “casula,” meaning “little house,” referring to how the garment envelops the wearer like a tent or covering.

- Different colors of chasubles mark the liturgical seasons and feast days, helping the faithful understand the rhythm of the Church year through visual symbols.

- The chasuble represents the priest’s role as mediator between God and humanity, specifically his function in offering the Eucharistic sacrifice.

- Understanding the chasuble’s history, symbolism, and proper use enriches Catholic appreciation for how the Church sanctifies material objects to express spiritual realities.

Ancient Origins and Roman Roots

The chasuble traces its ancestry to the paenula, a practical outdoor garment worn throughout the Roman Empire by people of all social classes. This circular or semicircular cloak featured a hole in the center for the head and fell in loose folds around the body. The paenula protected travelers from rain, wind, and cold during journeys on foot or horseback through the ancient world. Both men and women wore this versatile garment, which required no fastening devices like pins or buttons. The fabric draped naturally over the shoulders and arms, allowing freedom of movement while providing coverage. Wealthy Romans wore paenulae made from fine wool or silk, while common people used coarser materials. The garment’s simple construction made it accessible across economic levels, though quality varied with available resources. Early Christians living in the Roman Empire naturally wore paenulae as part of their everyday clothing. When they gathered for worship, they wore their ordinary garments including these practical cloaks. The transition from secular to sacred use happened gradually as Christian liturgical practice developed distinct forms.

By the fourth and fifth centuries, clergy began setting aside their finest clothing specifically for celebrating the Eucharist. The paenula worn for Mass started to differ from everyday versions in fabric quality, decoration, and symbolic intention. As Christian worship became more formalized after Constantine’s legalization of Christianity, liturgical vestments emerged as distinct categories. The paenula reserved for Mass became the chasuble, a garment dedicated exclusively to sacred use. Churches began maintaining collections of these special garments rather than having priests wear their personal clothing. The practice of blessing vestments before use set them apart from ordinary garments with similar appearance. Regional variations developed as different Christian communities adapted the basic paenula form to local aesthetics. Some areas favored fuller, more voluminous chasubles while others preferred more fitted designs. The essential characteristics remained constant despite these variations in detail and decoration. What began as practical outerwear became a sacred vestment with profound theological and liturgical significance.

Biblical and Theological Symbolism

The chasuble carries rich symbolic meaning rooted in both biblical imagery and theological reflection on priestly ministry. The garment’s enveloping nature recalls the seamless tunic worn by Jesus, which soldiers cast lots for at the crucifixion (John 19:23-24). This seamless robe symbolized Christ’s unity and the wholeness of His offering to the Father. The chasuble likewise represents the unity of Christ’s sacrifice and the priest’s participation in that one eternal offering. Traditional vesting prayers ask God to clothe the priest with charity, connecting the outer garment to inner virtue. The chasuble symbolizes the yoke of Christ, which priests take upon themselves in serving the Church (Matthew 11:29-30). This yoke, though real and demanding, brings rest rather than burden when accepted with faith and love. The priest wearing the chasuble visibly assumes Christ’s yoke, becoming His instrument in the sacred mysteries. The weight of the garment, especially in older fuller styles, served as a physical reminder of ministry’s spiritual weight.

The chasuble also symbolizes the charity that should characterize all priestly ministry and Christian life. Saint Paul teaches that love surpasses all other gifts and virtues, binding everything together in perfect harmony (Colossians 3:14). The chasuble as the outermost vestment represents charity as the supreme virtue that covers and completes all others. Just as the chasuble covers the other vestments, charity covers a multitude of sins and perfects Christian life (1 Peter 4:8). The priest vesting in the chasuble prepares to offer the sacrifice of love, Christ’s self-giving on the cross. This outer garment makes visible the invisible love that motivates authentic priestly service. The various colors of chasubles throughout the liturgical year express different aspects of God’s love revealed across salvation history. White chasubles proclaim the joy and glory of Christ’s resurrection and the saints’ triumph. Red chasubles mark both the fire of the Holy Spirit and the blood of martyrs who loved Christ unto death. Purple chasubles signify the penitential love that seeks reconciliation with God through conversion and amendment of life.

The Development of Liturgical Colors

The system of liturgical colors for chasubles and other vestments developed gradually over many centuries of Church practice. Early Christians used white garments for baptism and Eucharistic celebrations but lacked systematic color coding. The diversity of local customs meant that different churches used different colors for the same celebrations. Pope Innocent III in the early thirteenth century provided the first major attempt to standardize liturgical colors throughout the Western Church. His instructions established the basic framework that continues with modifications to the present day. White became the color for Christmas, Easter, and feasts of saints who were not martyrs. Red marked Pentecost, feasts of martyrs, and later Palm Sunday and Good Friday. Green indicated ordinary time when no special feast or season was being celebrated. Violet or purple served for Advent and Lent, the Church’s two major penitential seasons. Black was used for Masses for the dead and Good Friday in some traditions.

The post-Vatican II liturgical reforms maintained these traditional colors while allowing some flexibility and additions. Rose or pink chasubles may be worn on the third Sunday of Advent and fourth Sunday of Lent. These occasional bright colors provide visual relief during penitential seasons and express joyful anticipation. Blue chasubles appear in some places for Marian feasts, though this remains a permitted option rather than universal norm. Gold or white may substitute for other colors on solemn occasions, recognizing that some churches possess limited vestment collections. The symbolism of each color helps the faithful enter into the spirit of different liturgical times and celebrations. White expresses joy, purity, and glory in the resurrection and the communion of saints. Red symbolizes both the Holy Spirit’s transforming fire and the blood shed by martyrs and Christ Himself. Green represents hope, growth, and the ordinary progress of Christian life through time. Violet calls believers to penance, conversion, and preparation for encountering God in deeper ways. These colors work together to create a visual calendar that teaches even those who cannot read.

Evolution of Chasuble Design and Style

The chasuble’s physical form changed dramatically from ancient times to the present, reflecting practical needs and aesthetic preferences. The original paenula-style chasuble was truly circular or semicircular, draping fully around the priest’s body. This ample garment required significant fabric and created flowing, majestic lines during liturgical ceremonies. Medieval chasubles were extremely full, sometimes requiring assistants to lift the sides when the priest needed to extend his arms. Gothic chasubles maintained this fullness while featuring decorated orphreys, vertical and horizontal bands of contrasting fabric. The cross-shaped orphrey pattern created a visible cross on the chasuble’s back and sometimes front. Renaissance and Baroque periods saw gradual reduction in chasuble size for practical reasons related to movement. The so-called fiddleback or Roman chasuble emerged, with sides cut away to free the priest’s arms. This reduced style sacrificed medieval grandeur for practical functionality during Mass.

The liturgical movement of the twentieth century sparked renewed interest in fuller, more traditional chasuble designs. Reformers argued that the fiddleback chasuble had lost the garment’s essential character and symbolic meaning. They advocated returning to Gothic or paenula-style chasubles that better expressed the vestment’s nature as an enveloping outer garment. Post-Vatican II liturgical renewal generally favored these fuller styles, though both forms remain legitimate. Contemporary chasubles show great variety, from traditional full Gothic styles to modern simplified designs. Some feature elaborate embroidery, appliqué work, or woven patterns that create visual beauty and symbolic richness. Others embrace austere simplicity with plain fabrics and minimal decoration. The diversity reflects legitimate differences in aesthetic judgment and liturgical vision within Catholic unity. What matters most is not the specific style but that the chasuble be worthy of its sacred purpose and properly made.

Proper Use and Vesting Rituals

The priest puts on the chasuble as the final vestment, completing the process of robing for Mass. This layering follows a specific order that reflects both practical considerations and symbolic meanings. The priest begins with the amice, a white cloth placed around the neck and shoulders. Next comes the alb, the long white garment that covers ordinary clothing and symbolizes baptismal purity. The cincture, a rope or cloth belt, gathers the alb at the waist and represents spiritual discipline. The stole, a long strip of fabric in the liturgical color, goes around the neck and hangs down in front. Finally, the chasuble covers everything, representing charity that completes and perfects Christian virtue. Each vestment traditionally has an associated prayer that the priest says while putting it on. These prayers help transform the mechanical act of dressing into genuine spiritual preparation for celebrating Mass. The vesting prayers ask God for various graces needed to offer the sacred mysteries worthily and fruitfully.

The priest wears the chasuble throughout the Mass from the entrance procession to the final blessing and dismissal. He does not remove it for any part of the Eucharistic celebration, unlike some other vestments used in different ceremonies. The chasuble identifies the priest as the celebrant of the Mass, distinguishing him from deacons, servers, and concelebrating priests. When multiple priests concelebrate, they all wear chasubles in the appropriate liturgical color. This creates visual unity among the concelebrants while their shared vestments express their shared priesthood. The principal celebrant may wear a more elaborate chasuble, though this is not required. Some traditions distinguish the presider through position and gesture rather than different vestments. The chasuble remains on even when the priest sits during readings or after communion. Only at the very end of Mass does he remove the chasuble as part of the unvesting process. This constancy reflects the chasuble’s role as the distinctive vestment of Mass, worn only for this central act of Catholic worship.

Distinguishing the Chasuble from Other Vestments

The chasuble differs from the dalmatic, the outer vestment worn by deacons at Mass and other solemn liturgies. The dalmatic features sleeves and a more tunic-like construction compared to the chasuble’s enveloping design. This distinction in form reflects the different roles of priests and deacons in the liturgical celebration. Deacons assist the priest but do not themselves confect the Eucharist or pronounce the words of consecration. Their dalmatic marks this auxiliary role while still clothing them in a dignified outer vestment. The dalmatic and chasuble coordinate in color, creating visual harmony between priest and deacon at the altar. When a bishop celebrates Mass, he may wear a dalmatic under his chasuble, symbolizing the fullness of orders. This layering shows that bishops possess both the priesthood and the diaconate in their episcopal consecration. The combined vestments create a rich visual expression of sacramental theology and ecclesial structure.

The cope is another liturgical outer garment that sometimes causes confusion with the chasuble among those unfamiliar with Catholic practice. The cope resembles a elaborate cloak or cape, fastened at the chest with a clasp or morse. Priests wear copes for solemn celebrations outside of Mass, such as processions, Benediction, and the Liturgy of the Hours. The cope is never worn for Mass itself, where the chasuble alone serves as the proper outer vestment. This distinction maintains clarity about the different types of liturgical actions and their appropriate vesture. A priest might wear a cope for a wedding ceremony outside Mass but would wear a chasuble if celebrating the nuptial Mass. The cope’s openness in front contrasts with the chasuble’s closed, enveloping character. This difference reflects the distinct nature of the ceremonies for which each vestment is appropriate. Understanding these distinctions helps Catholics read the visual language of liturgical celebrations more fluently.

Materials, Craftsmanship, and Decoration

Traditional chasubles were made from silk, wool, or linen, with silk preferred for its beauty and luxurious drape. The finest chasubles featured silk damask or brocade woven in elaborate patterns that caught and reflected light beautifully. These precious fabrics honored God through beauty while creating garments worthy of the sacred mysteries celebrated. Skilled embroiderers decorated chasubles with religious symbols, scenes from Christ’s life, or abstract ornamental patterns. Gold and silver threads added brilliance and expressed the glory of divine worship through material splendor. The vestment’s back typically received more elaborate decoration since this side remained visible to the congregation throughout most of Mass. Front decoration varied, with some chasubles featuring matching designs and others leaving the front relatively plain. The orphreys or decorative bands often incorporated images of saints, biblical scenes, or symbolic motifs. These artistic elements made each chasuble unique while communicating theological truths through visual beauty.

Modern chasubles employ diverse materials including synthetic fabrics that offer practical advantages over natural fibers. Polyester and other synthetics resist wrinkling, clean easily, and maintain their appearance with minimal care. These practical benefits make them attractive for parishes with limited resources for vestment maintenance. However, natural fabrics continue to have advocates who argue they better serve the chasuble’s dignity and symbolic purposes. Silk breathes better, drapes more beautifully, and feels more appropriate for sacred use than artificial materials. The debate between tradition and practicality continues in discussions about proper vestment materials and construction. Many churches maintain both types, using fine traditional chasubles for solemn occasions and synthetic ones for ordinary Sundays. The essential requirement remains that chasubles be clean, well-made, and appropriate for divine worship. Shabby, poorly maintained chasubles dishonor the liturgy regardless of their material composition or historical pedigree.

The Chasuble and Priestly Identity

The chasuble serves as a powerful external sign of the priest’s sacred identity and mission in the Church. When a man is ordained to the priesthood, he receives the authority and responsibility to celebrate Mass. The chasuble becomes the visible expression of this priestly power to offer sacrifice on behalf of God’s people. Newly ordained priests often receive their first chasuble as an ordination gift from family, friends, or their seminary. This personal chasuble accompanies them throughout their priestly ministry, becoming a treasured possession and companion. The act of putting on the chasuble each day for Mass reminds the priest of his ordination and calling. The garment becomes familiar through repeated use yet retains its significance as a sacred vestment. Priests develop personal relationships with their chasubles, which witness and enable their daily offering of the Eucharistic sacrifice. Some priests maintain their first chasuble throughout their entire ministry, while others acquire new ones over the years.

The chasuble also shapes how others perceive and relate to the priest during liturgical celebrations. When Catholics see a priest vested in a chasuble, they recognize him as acting in persona Christi, in the person of Christ. The vestments signal that the priest serves in an official capacity rather than as a private individual. This distinction helps maintain appropriate boundaries and proper understanding of sacramental ministry. The priest’s personality becomes secondary to his function as mediator and instrument of Christ’s saving action. The chasuble covers the priest’s ordinary clothing and individual characteristics, directing attention toward the sacred mysteries. This veiling of personal identity serves the liturgy’s goal of making Christ present rather than showcasing human performers. Yet the priest remains himself, not becoming an actor playing a role. The chasuble enhances rather than replaces his genuine human participation in the divine mysteries. This balance between personal and sacramental identity defines healthy priestly ministry and self-understanding.

Regional and Cultural Variations

Different Catholic cultures developed distinctive chasuble styles that reflect local artistic traditions and aesthetic sensibilities. Spanish chasubles often featured bold colors, dramatic contrasts, and elaborate gold embroidery influenced by Moorish artistic traditions. French vestments tended toward refined elegance with subtle coloring and restrained decoration characteristic of French taste. Italian chasubles showed Renaissance and Baroque influences, with classical proportions and rich ornamentation. German and Central European vestments often displayed solid craftsmanship with Gothic architectural motifs and heraldic designs. English chasubles before and after the Reformation developed their own character, though many were destroyed during periods of religious upheaval. These regional styles enriched the universal Church with particular cultural expressions of common liturgical practices. Modern vestment makers sometimes revive historical regional styles, creating contemporary chasubles inspired by traditional designs. This recovery of traditional forms serves both aesthetic and spiritual purposes, connecting present practice to historical roots.

Eastern Catholic churches have their own liturgical vestments that serve functions similar to the Latin chasuble while differing in form. The phelonion worn by Byzantine priests resembles the chasuble in being the outer Eucharistic vestment. However, its construction and symbolic associations reflect Eastern theological emphases and liturgical customs. Other Eastern traditions use vestments with different names, forms, and decorative conventions. These variations demonstrate how the same liturgical needs find expression through different cultural lenses and historical developments. Western Catholics attending Eastern liturgies can recognize familiar patterns despite unfamiliar forms and terms. The phelonion and chasuble both clothe priests for offering the Eucharistic sacrifice, though their appearances differ. This unity in diversity characterizes Catholic worship, where essential elements remain constant across legitimate variations. Understanding these differences prevents confusion and promotes appreciation for the Church’s rich liturgical heritage.

Care, Maintenance, and Stewardship

Proper care of chasubles reflects respect for sacred objects and good stewardship of parish resources. Chasubles should be cleaned regularly according to the specific requirements of their fabric and construction. Professional dry cleaning services familiar with liturgical vestments can provide expert care for valuable or delicate chasubles. Some modern synthetic chasubles can be machine washed, though care must still be taken to prevent damage. Priests should avoid eating or drinking while wearing chasubles to prevent stains and spills. After use, chasubles should be hung on proper hangers that support their weight without stretching or distorting the fabric. Storage areas must protect chasubles from dust, moisture, excessive light, and insect damage. Cedar closets or sachets can deter moths that might damage natural fiber vestments. Regular inspection allows early detection of needed repairs before minor problems become major damage. Small tears, loose seams, or missing decorative elements should be repaired promptly by skilled hands.

Parish vestment committees or sacristans typically assume responsibility for maintaining chasuble collections and ensuring proper care. Clear inventory systems track which chasubles exist, their condition, and when they need cleaning or repair. Rotation schedules ensure even wear across multiple chasubles rather than overusing favorites while others languish unused. Budget planning includes funds for periodic professional cleaning, repairs, and eventual replacement of worn-out vestments. Some parishes establish vestment endowments or memorial funds that accept donations for purchasing or maintaining liturgical garments. Donors appreciate opportunities to contribute beautiful vestments in memory of loved ones or thanksgiving for blessings. Plaques or registry books may record these donations, honoring benefactors while maintaining proper focus on worship. When chasubles become too damaged for repair or use, proper disposal respects their sacred character. Some parishes ceremonially burn unusable vestments rather than discarding them as ordinary trash. These practices express the reverence due to objects blessed and set apart for divine service.

The Chasuble in Contemporary Practice

Modern priests face questions about when to wear chasubles and what styles best serve contemporary liturgical needs. The chasuble remains mandatory for celebrating Mass, though some priests in the immediate post-Vatican II period experimented with alternatives. Current Church law clearly requires the chasuble for the Eucharistic celebration, ending debates about optional use. However, legitimate diversity exists regarding style, decoration, and aesthetic approach to vestment design. Some priests favor traditional full Gothic chasubles that create dramatic visual impact during liturgical ceremonies. Others prefer modern simplified designs with clean lines and minimal decoration. Both approaches can serve reverent worship when properly executed and motivated by appropriate principles. The choice often reflects broader liturgical sensibilities about the relationship between beauty, simplicity, and transcendence. Traditional aesthetics emphasize continuity with the past and the timeless nature of Catholic worship. Contemporary designs seek to express eternal truths through current artistic vocabularies and materials.

Debates about vestment styles sometimes reveal deeper disagreements about the nature of liturgy and priesthood itself. Those favoring elaborate traditional vestments often emphasize the sacred, set-apart character of ordained ministry. They value visual beauty as appropriate for divine worship and reject excessive austerity as false humility. Advocates of simpler styles argue for noble simplicity that focuses attention on the Eucharist rather than on vestments. They worry that excessive decoration becomes distraction or suggests clericalism and privilege. These tensions require patience, charity, and recognition that legitimate differences can exist within Catholic unity. What matters most is not settling every aesthetic question but maintaining reverence and proper intention. A simple modern chasuble worn with devotion serves better than an elaborate historical one worn with vanity. Conversely, traditional beauty honors God when appreciated as gift rather than possessed with pride. The Church allows diversity in these matters while insisting on fundamental reverence and appropriate dignity.

Teaching Opportunities About the Chasuble

The chasuble provides catechists and clergy with concrete opportunities to teach about priesthood, liturgy, and sacramental theology. Children preparing for First Communion can learn that the priest’s special clothes have special meanings. Simple explanations about the chasuble representing charity and Christ’s yoke make abstract concepts accessible. Showing different colored chasubles helps children understand the Church year’s rhythm and the meaning of various seasons. Purple for Advent and Lent, white for Christmas and Easter, red for Pentecost become familiar patterns. This visual learning reinforces verbal catechesis and helps children participate more consciously in Mass. School groups visiting churches can see vestments up close and ask questions about their use and meaning. Priests explaining why they wear different colors on different Sundays plant seeds of liturgical understanding.

Adult faith formation likewise benefits from exploring vestment symbolism and its theological foundations. Many adult Catholics have observed chasubles for years without understanding their significance or history. RCIA programs should include teaching about liturgical symbols, practices, and their meanings for Christian life. Candidates and catechumens can learn how physical objects like the chasuble express invisible spiritual realities. Parish lectures or study groups examining liturgical vestments can deepen appreciation for Catholic worship’s richness. Explaining the chasuble’s evolution from Roman cloak to sacred vestment illustrates how the Church sanctifies culture. The connection between the seamless garment of Christ and the chasuble opens reflection on unity and sacrifice. Teaching about proper care of vestments can inspire volunteers to assist with this important ministry. These various educational approaches help Catholics move from passive attendance to active, intelligent participation in the liturgy (CCC 1141).

The Chasuble and Eucharistic Theology

The chasuble bears intimate connection to Catholic teaching about the Eucharist as true sacrifice offered to God. The priest wearing the chasuble offers the sacrifice of the Mass in persona Christi capitis, in the person of Christ the head. This sacrificial character distinguishes the Mass from all other forms of prayer or worship. The chasuble visually marks this distinction, worn only when the priest confects the Eucharist and offers it to the Father. Other liturgical vestments serve other purposes, but the chasuble specifically clothes the priest for Eucharistic sacrifice. The garment’s enveloping nature symbolizes the priest’s complete participation in Christ’s self-offering on the cross. Just as the chasuble covers the priest entirely, Christ’s sacrifice covers all sin and reconciles humanity to God. The priest does not offer a new sacrifice but makes present the one eternal offering of Calvary. The chasuble worn across centuries connects contemporary celebrations to that historical event and its perpetual efficacy.

The chasuble also relates to Catholic teaching about the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The priest’s vestments create appropriate context for the awesome mystery that unfolds at the altar. When bread and wine become Christ’s Body and Blood, the celebrant should be clothed in garments worthy of this encounter. The chasuble serves this purpose, elevating the visual and symbolic register of the celebration. Its beauty and distinctiveness help create sacred space where heaven and earth meet sacramentally. The care taken in vestment design, maintenance, and use reflects faith in what actually happens during Mass. Churches that invest in beautiful chasubles express belief that something genuinely supernatural occurs at the altar. Conversely, shabby or careless treatment of vestments can suggest doubt about the Mass’s true nature and importance. The external symbols should match the internal reality they serve and express to the community.

Challenges and Questions in Modern Context

Contemporary priests sometimes struggle with wearing elaborate vestments in contexts of poverty or social inequality. A priest celebrating Mass in a wealthy suburban parish faces different questions than one serving an impoverished community. Wearing expensive silk chasubles while parishioners lack basic necessities can seem inconsistent with the Gospel’s call to solidarity. Some priests deliberately choose simpler vestments to avoid appearing separated from ordinary people’s lives and struggles. Others argue that beautiful vestments honor God and give poor communities dignity through worthy worship. The debate touches fundamental questions about how Christians should relate to beauty, material goods, and social justice. Jesus accepted expensive perfume poured on His feet, defending this lavish gesture against practical objections (John 12:3-8). Yet He also insisted that His followers serve the poor and share their resources with those in need. The tension between these imperatives requires wisdom and cannot be resolved through simple rules.

Environmental concerns add another dimension to contemporary vestment questions and practices regarding materials and production. Synthetic fabrics, while practical, come from petroleum products and contribute to pollution and resource depletion. Natural fibers like silk involve complex supply chains with potential ethical problems regarding labor and environmental impact. Fair trade and sustainably produced vestments remain difficult to source and often cost significantly more. Parishes trying to be good stewards of creation face genuine dilemmas about vestment choices. Some seek vintage or used chasubles, recycling existing vestments rather than purchasing new ones. Others commission new vestments from local artisans using ethical materials and production methods. These practical decisions reflect broader questions about how Catholics live their faith in a complex modern world. The chasuble becomes a focal point for thinking through these issues precisely because it matters and carries meaning.

The Future of the Chasuble

The chasuble will certainly continue as the distinctive vestment for Mass throughout the foreseeable future of Catholic worship. This garment’s long history and deep theological significance ensure its persistence despite changing fashions and sensibilities. Future generations of priests will don chasubles just as countless generations have done before them. However, specific styles, materials, and decorative approaches will likely continue evolving as they have throughout Church history. Contemporary movements favoring traditional forms may preserve or revive historical styles currently less common. Alternatively, new artistic expressions may emerge that honor the chasuble’s essential nature while embracing modern aesthetics. The tension between preservation and innovation will continue shaping how chasubles look and feel in practice. What remains constant is the garment’s fundamental purpose and meaning in Catholic worship and priestly identity.

The chasuble also will continue serving as a teaching tool and symbol that communicates truths about priesthood and Eucharist. Visual symbols matter in a world increasingly shaped by images and immediate visual communication. The chasuble’s distinctive appearance makes it memorable and recognizable even to those unfamiliar with Catholicism. This visibility creates opportunities for explanation and evangelization when curious observers ask questions. The colored chasubles marking different seasons create patterns that even children can recognize and remember. These simple visual cues build liturgical literacy across generations and cultural contexts. As long as Catholics gather for Mass, the priest will vest in the chasuble that marks him as celebrant. This continuity across time connects contemporary believers to their ancestors in faith and to future generations yet unborn.

Conclusion

The chasuble endures as a meaningful and necessary element of Catholic liturgical tradition and practice. This distinctive vestment developed from common Roman clothing into a sacred garment with profound theological significance. The chasuble symbolizes charity, Christ’s yoke, and the priest’s participation in the Eucharistic sacrifice. Its various colors mark the liturgical seasons and help the faithful enter into different aspects of salvation history. The evolution of chasuble styles reflects changing aesthetic sensibilities while maintaining essential symbolic meanings. Proper care and use of chasubles express reverence for sacred objects and the mysteries they serve. Regional variations demonstrate how universal truths find expression through particular cultural forms and artistic traditions. Teaching about the chasuble provides opportunities for catechesis that deepens liturgical understanding and appreciation. Contemporary debates about vestment styles touch deeper questions about beauty, simplicity, and authentic worship. The chasuble’s future remains secure as an essential component of Catholic Eucharistic celebration.

The chasuble ultimately points beyond itself to the priesthood of Christ and His eternal sacrifice for humanity’s salvation. Every priest who wears the chasuble shares in that one priesthood and offers that one sacrifice. The garment makes visible the invisible grace and authority conferred through Holy Orders (CCC 1536-1600). As Catholics understand the chasuble’s rich symbolism and history, they participate more fully in the Mass with both mind and heart. The white, red, green, and purple chasubles throughout the year tell the story of God’s love revealed in Christ. May this ancient vestment continue to serve the Church faithfully, clothing priests who offer the Eucharistic sacrifice and leading believers deeper into the mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection, now and forever.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.