Brief Overview

- Catholics and Protestants read the same Bible but often arrive at different understandings of Mary’s role in salvation history.

- The angel Gabriel addressed Mary as “full of grace” in Luke’s Gospel, a phrase that reveals her unique spiritual state before God.

- Elizabeth proclaimed Mary “blessed among women” and recognized her as “the mother of my Lord,” acknowledging her special dignity.

- Mary herself prophesied that all generations would call her blessed, a statement that continues to shape Catholic devotion today.

- The early Church Fathers identified Mary as the New Eve, seeing a parallel between Eve’s disobedience and Mary’s obedient yes to God.

- Catholic teaching about Mary draws from Scripture, apostolic tradition, and two thousand years of theological reflection guided by the Holy Spirit.

Understanding the Different Perspectives on Mary

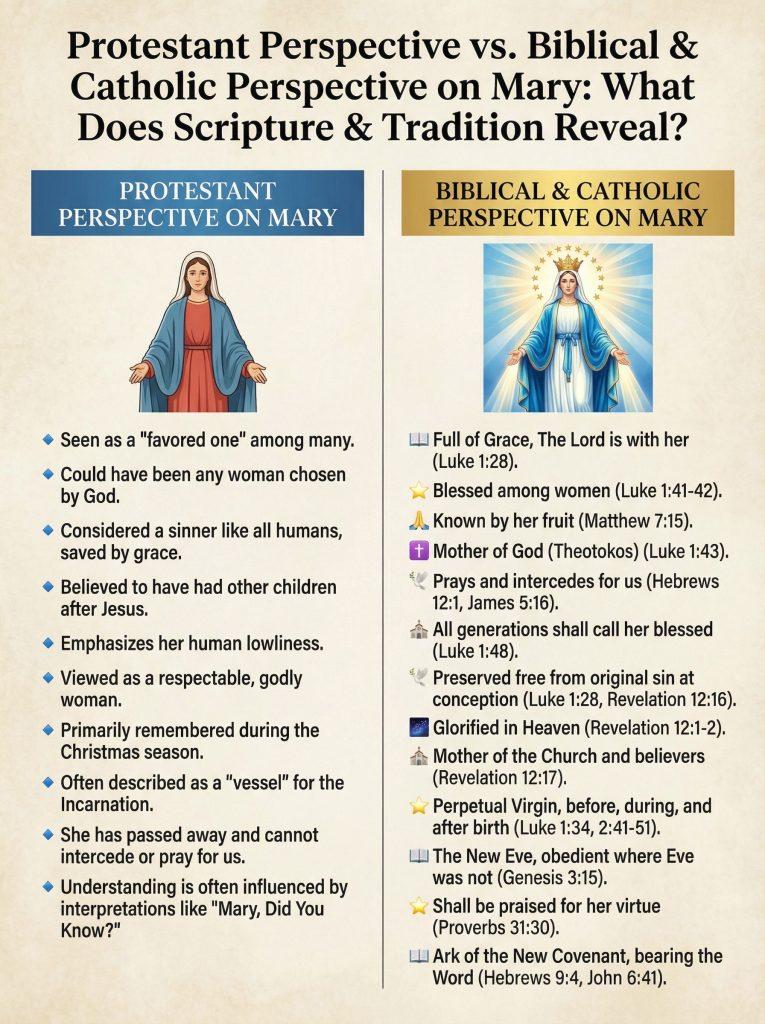

The debate between Protestant and Catholic views of Mary often centers on whether Catholic teaching adds to Scripture or faithfully interprets it. Many Protestants see Catholic Marian doctrine as extrabiblical tradition that goes beyond what the Bible actually says about Jesus’s mother. They argue that the simple biblical portrait shows Mary as a godly woman chosen for a special task but not deserving the titles and honors Catholics give her. From this perspective, Catholic practices like praying to Mary, calling her the Mother of God, and believing in her Immaculate Conception and Assumption represent human traditions rather than biblical truth. Some worry that Catholic devotion to Mary borders on worship or at least takes attention away from Christ. These concerns stem from sincere desire to remain faithful to Scripture and give Christ alone the glory he deserves. The Protestant approach generally emphasizes Mary’s humanity and ordinariness, seeing her as a humble servant who should not be elevated above other believers. This perspective values Mary’s example of faith while rejecting what it sees as excessive Catholic elaboration. The question becomes whether Catholic teaching represents legitimate development of biblical themes or departure from scriptural foundations. Examining what Scripture actually says about Mary provides the starting point for understanding this disagreement.

The Catholic perspective argues that Protestant views often minimize what Scripture reveals about Mary’s unique role and dignity. Catholics contend that their teaching develops organically from biblical foundations rather than adding foreign elements to the faith. The titles and doctrines surrounding Mary arose from the Church’s reflection on scriptural texts under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Catholic interpretation reads individual biblical passages about Mary within the broader context of salvation history and Christian tradition. This approach sees connections and implications in the biblical text that might not be immediately obvious from a surface reading. Catholics argue that the early Christian community, which produced and preserved the New Testament, also passed on authentic understanding of Mary’s role. The Protestant principle of sola scriptura, Scripture alone, developed in the sixteenth century, while Christian teaching about Mary dates to the earliest centuries. Catholic scholars point out that nowhere does the Bible teach that Scripture alone is the sole rule of faith. The New Testament writings emerged from and presuppose the living tradition of the apostolic Church. Understanding Mary requires attention to this fuller context rather than isolating biblical texts from the tradition that produced them. The Catholic approach sees Protestant views as reading Scripture through modern lenses that remove it from its historical and ecclesial context.

Both perspectives claim fidelity to the biblical witness, yet they arrive at significantly different conclusions about Mary’s identity and role. Part of the disagreement stems from different hermeneutical principles and assumptions about authority. Protestants generally emphasize the clarity and sufficiency of Scripture, believing that essential truths should be plainly evident from the biblical text. Catholics emphasize the role of the Church in interpreting Scripture authentically under the Holy Spirit’s guidance. These different starting points lead to different readings of the same biblical passages. The debate also reflects broader theological differences about the nature of the Church, the authority of tradition, and the development of doctrine. Neither side denies that Mary was a historical person chosen by God for a unique mission. The disagreement concerns what that mission implies about her character, her continuing role, and the appropriate response of believers. Examining specific biblical texts about Mary helps clarify what Scripture actually reveals. The question is not whether Scripture speaks about Mary but how to understand and apply what it says. Both Catholics and Protestants can benefit from careful attention to the biblical data and honest engagement with how Christians have understood these texts throughout history.

The pastoral implications of this debate affect how Christians relate to Mary in their spiritual lives. For many Protestants, mentioning Mary only at Christmas or as an example of obedience seems sufficient and appropriate. Catholics experience Mary as a living presence who continues to care for believers as their spiritual mother. These different approaches shape prayer, liturgy, and personal devotion in significant ways. Some Christians worry that any increased attention to Mary will inevitably lead to the perceived Catholic excesses. Others feel that Protestant neglect of Mary impoverishes Christian faith and ignores biblical teaching. The emotional dimensions of this debate often complicate rational discussion, as people’s relationship to Mary connects to deep-seated religious identity. Finding common ground requires willingness to examine Scripture carefully and charitably consider alternative interpretations. The goal should be understanding what God reveals through the biblical witness rather than defending predetermined positions. Mary herself points beyond herself to Jesus, as her words at Cana indicate: “Do whatever he tells you.” Both Catholic and Protestant Christians can agree that Mary’s example calls believers to faith, obedience, and complete dedication to God’s will. Building on this foundation allows honest exploration of where the two traditions differ and why.

The Biblical Foundation for Catholic Marian Doctrine

The Catholic Church’s understanding of Mary stems directly from careful reading of Sacred Scripture and the lived tradition of the early Christian community. When we examine the biblical texts closely, we find a portrait of Mary that goes far beyond a simple supporting character in the Christmas story. The Gospel accounts, particularly Luke’s narrative, present Mary as a woman uniquely prepared by God for her mission as the Mother of the Savior. Her role in salvation history carries theological significance that the early Christians recognized and celebrated from the beginning. The apostolic Church understood Mary’s cooperation with God’s plan as essential to the Incarnation itself. This understanding developed organically as believers reflected on what Scripture revealed about her character and calling. The titles and honors given to Mary in Catholic teaching flow naturally from the biblical data when read through the lens of tradition. Modern Catholics continue this same practice of reading Scripture in communion with the Church that produced it. The biblical witness to Mary remains clear and compelling when examined without preconceived limitations. Understanding what Scripture says about Mary requires attention to both explicit statements and implicit theological themes.

The Greek text of Luke’s Gospel provides crucial insights into how the early Church understood Mary’s identity and mission. When the angel Gabriel appears to Mary in Luke 1:28, he greets her with a word that English translations often render simply as “favored one” or “highly favored.” However, the Greek word used is kecharitomene, a perfect passive participle of the verb charitoo, which means to fill with grace or to make full of grace. This grammatical form indicates a completed action with ongoing results, meaning Mary had already been filled with grace before the angel’s arrival. The choice of this particular word form suggests something about Mary’s state that goes beyond a momentary divine favor. Gabriel addresses her by this title as if it were her name, identifying her by her grace-filled status. This greeting stands out as unique in all of Scripture, used for no other person in the biblical text. The angel’s words point to God’s prevenient work in Mary’s life, preparing her for the role she would accept. Catholic theology sees in this greeting the biblical foundation for the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. The phrase indicates that Mary possessed a fullness of grace that distinguished her among all women. This understanding connects directly to her calling as the Mother of God made flesh.

Elizabeth’s response to Mary’s visit provides additional biblical evidence for Mary’s unique status in God’s plan. When Mary enters Elizabeth’s home in Luke 1:39-45, Elizabeth greets her with inspired words that reveal deep theological truths. Elizabeth calls Mary “blessed among women,” using a phrase that sets Mary apart from all other women in history. She then asks a remarkable question, wondering why “the mother of my Lord” should come to visit her. This title, “mother of my Lord,” carries enormous theological weight when we recognize that Elizabeth refers to Jesus as Lord, the same title used for God throughout the Old Testament. Elizabeth recognizes Mary’s divine maternity and responds with appropriate honor and humility. The Holy Spirit inspires Elizabeth’s greeting, making it more than personal admiration or family courtesy. Elizabeth also blesses Mary for her faith, saying that she is blessed because she believed what the Lord had spoken to her. This blessing connects Mary’s unique status to her faithful response to God’s word. The infant John leaps in Elizabeth’s womb at Mary’s greeting, a sign of the sanctifying presence she brings. Elizabeth’s inspired words testify to the early Church’s understanding of Mary’s role and dignity. The scene demonstrates that honoring Mary appropriately has biblical precedent from the very beginning of Jesus’s life.

Mary’s own words in the Magnificat reveal her prophetic understanding of her role in salvation history. In Luke 1:46-55, Mary breaks into a canticle of praise that echoes the song of Hannah in 1 Samuel 2:1-10. She begins by magnifying the Lord and rejoicing in God her Savior, acknowledging her complete dependence on divine grace. Mary then makes a striking prophetic statement in Luke 1:48, declaring that “all generations will call me blessed.” This prophecy has been fulfilled throughout Christian history as believers in every age have honored Mary as blessed. The phrase “all generations” indicates a universal and perpetual recognition that transcends cultural and temporal boundaries. Mary understood that her role as Mother of the Messiah would have lasting significance for all who come to faith. Her prophecy provides biblical warrant for the Catholic practice of calling Mary blessed and honoring her memory. The Magnificat also reveals Mary’s deep knowledge of Scripture and her identification with God’s saving work among the poor and humble. She sees herself as part of God’s ongoing plan to fulfill the promises made to Abraham and his descendants. Mary’s canticle demonstrates her prophetic voice and theological insight. The early Church treasured these words and incorporated them into Christian prayer and liturgy.

The question of Mary’s perpetual virginity finds support in careful reading of the biblical texts. When Gabriel announces that Mary will conceive and bear a son in Luke 1:31, Mary responds with a puzzling question in Luke 1:34, asking, “How can this be, since I know not man?” This response seems strange if Mary were simply a young woman about to be married who expected normal marital relations with Joseph. The natural understanding of pregnancy would have been obvious to any engaged woman in first-century Judea. Mary’s question makes more sense if she had made a commitment to virginity, a practice known among some Jewish women of her time. Her inquiry suggests that she needs to understand how pregnancy can occur without marital relations. Gabriel then explains that the Holy Spirit will accomplish this miraculous conception. Joseph’s role as Mary’s husband involves protecting and providing for her and Jesus, but Matthew’s account notes that he “knew her not” until after Jesus was born. The Greek word translated “until” does not necessarily imply a change after the specified time, just as we might say someone was faithful “until death” without implying infidelity afterward. References to Jesus’s “brothers” in the Gospels can be understood as cousins or close relatives, as both Hebrew and Aramaic lacked separate words for these relationships. The early Church universally taught Mary’s perpetual virginity from the second century onward. This belief reflects the understanding that Mary’s entire being was consecrated to her unique vocation as Mother of God.

The Title Mother of God and Its Biblical Basis

The Catholic practice of calling Mary “Mother of God” or Theotokos often confuses or troubles those unfamiliar with the theological reasoning behind this title. Some people mistakenly think Catholics are suggesting that Mary existed before God or that she somehow created the divine nature. The title actually expresses a crucial truth about Jesus Christ himself rather than claiming anything impossible about Mary. When we say Mary is the Mother of God, we affirm that the person to whom she gave birth is truly God. The doctrine addresses the question of who Jesus is rather than making claims about Mary’s power or nature. Mary conceived and bore not just a human person who would later become divine, but the eternal Son of God taking on human flesh. The Council of Ephesus in 431 AD formally defined this teaching in response to the Nestorian heresy, which tried to separate Christ’s human and divine natures so radically that he became two persons. The title Theotokos preserves the biblical truth that Jesus is one divine person with two natures, human and divine. Mary is mother of the person of Christ, who is God the Son incarnate. This understanding flows directly from Scripture’s testimony about Jesus’s identity.

The Gospel of John provides clear biblical basis for understanding Jesus as the eternal Word of God who became flesh. John’s prologue declares in John 1:1 that “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” This Word, who is identified as the second person of the Trinity, “became flesh and dwelt among us” according to John 1:14. The Incarnation means that the eternal God entered into human existence through the womb of Mary. When Mary conceived Jesus, she conceived a divine person who was taking on human nature. She carried in her womb the one through whom all things were made, the eternal Son of the Father. Thomas’s confession in John 20:28, “My Lord and my God,” identifies the risen Jesus as divine. Paul writes in Philippians 2:6-7 that Christ Jesus, though being in the form of God, emptied himself and took the form of a servant, being born in human likeness. The Letter to the Hebrews emphasizes that Jesus is the exact imprint of God’s nature who made purification for sins. These texts establish that Jesus is truly God, the second person of the Trinity. If Jesus is God, and Mary is the mother of Jesus, then Mary is the mother of God incarnate. The logic is straightforward once we understand what the Incarnation means.

The alternative to calling Mary the Mother of God leads to problematic understandings of Christ himself. If we say Mary is only the mother of Jesus’s human nature but not the mother of his person, we risk dividing Christ into two separate persons. This was precisely the error of Nestorius, who wanted to call Mary Christotokos, “Christ-bearer,” instead of Theotokos, “God-bearer.” The Church rejected this terminology because it failed to express the unity of Christ’s person. We do not say that Mary is merely the mother of Jesus’s body while someone or something else is the mother of his soul or divinity. Mothers give birth to persons, not to natures or body parts. Mary gave birth to the person of Jesus Christ, who is the eternal Son of God in human flesh. The hypostatic union, the union of divine and human natures in the one person of Christ, means we cannot separate what we say about Jesus into divine and human categories. When Mary nursed Jesus, God was being nursed. When Jesus grew in wisdom and stature, God was growing in his human nature. The title Mother of God protects these essential truths about the Incarnation. Refusing this title often indicates an inadequate understanding of who Jesus is.

The scriptural witness to Jesus’s identity makes the title Mother of God not only appropriate but necessary for orthodox faith. Gabriel tells Mary in Luke 1:32 that her son “will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High.” The angel goes on to say that “the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David” and that “of his kingdom there will be no end.” These statements identify Jesus with the eternal divine kingship. Elizabeth’s question, “Why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me,” uses the term “Lord” in a way that suggests divinity. Throughout the Old Testament, “Lord” translates the divine name revealed to Moses. When Elizabeth calls Jesus her Lord, she recognizes something more than ordinary human authority. The shepherds in Luke 2:11 are told that “there is born to you this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord.” The titles pile up to indicate Jesus’s divine identity from his birth. Matthew’s Gospel identifies Jesus as Emmanuel, meaning “God with us,” in Matthew 1:23. These biblical titles and descriptions point to the same reality that the title Mother of God expresses. Mary bore the one who is truly divine as well as truly human. The Council of Ephesus simply gave dogmatic form to what Scripture teaches about Jesus and therefore about Mary’s relationship to him.

Mary as the New Eve in Biblical Typology

The early Church Fathers recognized a profound typological relationship between Eve and Mary that illuminates salvation history. Biblical typology involves seeing patterns and connections between Old Testament figures or events and their New Testament fulfillment. Just as Adam prefigures Christ, with Paul calling Christ the “last Adam” in 1 Corinthians 15:45, so Eve prefigures Mary. The parallel works through contrast and reversal rather than simple repetition. Eve, the mother of all the living according to Genesis 3:20, brought death into the world through her disobedience. Mary, by her obedient yes to God’s plan, brought the source of eternal life into the world. The disobedience of the first woman finds its remedy in the obedience of the second. This typological reading appears in Christian writings as early as the second century with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. The pattern reveals how God works through human cooperation in both fall and redemption. Eve listened to the serpent and brought about the fall; Mary listened to the angel and made possible the Incarnation. The contrast helps us understand how God’s saving plan involved undoing the damage of original sin.

The biblical texts themselves suggest this typological connection even if they do not make it explicit. The announcement to Mary takes place in the context of God’s promise in Genesis 3:15 to put enmity between the serpent and the woman. This proto-evangelium, the first gospel promise, speaks of the woman’s offspring crushing the serpent’s head. Christian tradition has long seen Mary as the woman whose son would defeat Satan. The Gospel of John’s account of the wedding at Cana and the crucifixion both have Jesus addressing Mary as “woman,” a formal and somewhat unusual form of address. At the cross, Jesus says to his mother in John 19:26-27, “Woman, behold your son,” and to the beloved disciple, “Behold your mother.” This address recalls the “woman” of Genesis and suggests Mary’s representative role. The Book of Revelation describes in Revelation 12:1-6 a great sign in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun who gives birth to a male child destined to rule all nations. This woman is pursued by the dragon but protected by God. While the primary reference is probably to Israel or the Church, the Fathers saw Mary represented in this image as well. The woman of Revelation connects to the woman of Genesis through the imagery of the serpent or dragon. These biblical echoes support the typological reading that sees Mary as the New Eve.

Understanding Mary as the New Eve helps explain her unique role in God’s plan of salvation. Just as Eve was created without sin and then fell through disobedience, Mary was preserved from sin and remained obedient throughout her life. The Immaculate Conception, Mary’s preservation from original sin from the moment of her conception, fits within this typological framework. God prepared Mary to be a fitting mother for his Son by preserving her from the stain of original sin that affects all other descendants of Adam and Eve. This preparation does not mean Mary did not need redemption; rather, she was redeemed in anticipation of Christ’s saving work. The grace that fills Mary comes from Christ’s merits applied to her in a special way. Her sinlessness throughout life parallels Eve’s original state before the fall. Where Eve failed, Mary succeeded, remaining faithful to God even through the terrible suffering of watching her son die on the cross. The parallel between Eve and Mary shows how God involves human persons in both the problem of sin and its solution. Mary’s cooperation with grace reversed the damage of Eve’s cooperation with temptation.

The New Eve typology also illuminates Mary’s spiritual motherhood of all believers. Eve received the name “mother of all the living” even after the fall, anticipating the life that would continue through her descendants. Mary becomes mother of all who live through Christ by her unique participation in his redeeming work. At the foot of the cross, Jesus gave Mary to the beloved disciple as mother and gave the disciple to Mary as son. This scene represents more than Jesus providing for his mother’s physical care after his death. The beloved disciple represents all disciples, all who love Jesus and follow him. Jesus establishes a relationship between Mary and all believers that mirrors the relationship between Eve and all humanity. Where Eve passed on the inheritance of sin and death, Mary gives us Christ who is life itself. Her spiritual motherhood flows from her physical motherhood of Jesus, extending her maternal care to all members of his Body. The Church has understood Mary as mother of all the redeemed since the earliest centuries. This understanding connects directly to the Eve-Mary typology that Scripture suggests and tradition develops. Mary’s role in salvation history affects all who receive salvation through her son.

The Communion of Saints and Mary’s Intercession

Catholic belief in Mary’s intercession for believers on earth rests on the biblical teaching about the communion of saints. Death does not separate members of Christ’s Body from one another or from Christ himself. Paul writes in Romans 8:38-39 that neither death nor life can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus. This means that those who have died in Christ remain united to the Church on earth through the bond of charity. The Letter to the Hebrews describes in Hebrews 12:1 how believers are “surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses,” referring to the faithful who have gone before. These witnesses remain interested in and connected to the ongoing life of the Church. The Book of Revelation shows the prayers of the saints being offered before God’s throne in Revelation 5:8, where the twenty-four elders hold golden bowls full of incense which are the prayers of the saints. This image demonstrates the intercessory role of the redeemed in heaven. They present prayers to God on behalf of those still on the earthly pilgrimage. The communion of saints means that the Church in heaven and the Church on earth form one family in Christ.

The practice of asking Mary to pray for us follows naturally from asking fellow Christians on earth to pray for us. James writes in James 5:16 that “the prayer of a righteous person has great power as it is working.” If the prayers of righteous people on earth are powerful, how much more the prayers of the perfectly righteous in heaven who see God face to face. Mary, full of grace and blessed among women, prays with perfect love and perfect alignment with God’s will. Asking her to pray for us simply means requesting the prayers of the holiest human person God has created. Catholics do not believe Mary has power independent of God or that she grants prayers by her own authority. All prayer, whether from those on earth or those in heaven, goes to God as the source of all grace. Mary’s intercession consists in bringing our needs before her son, as she did at the wedding in Cana. In John 2:1-11, Mary notices that the wine has run out and brings this need to Jesus’s attention. Jesus responds to his mother’s request by performing his first miracle. This scene provides a biblical model for Mary’s continuing intercessory role. She brings our needs to Jesus, and he responds to his mother’s requests.

Some people object that we can go directly to Jesus and therefore do not need Mary’s intercession. This objection misunderstands the nature of intercessory prayer and the communion of saints. We can indeed go directly to Jesus, and Catholics do so regularly in personal prayer and in the liturgy. Asking Mary or other saints to pray for us does not replace direct prayer to God. It supplements and enriches our prayer by joining it to the prayers of the whole Church, living and deceased. When we ask a friend on earth to pray for us, we do not think this bypasses Jesus or shows lack of faith in his saving power. We recognize that the Body of Christ prays together and members can ask one another for prayer support. The same principle applies to asking the saints in heaven to pray for us. Paul frequently asks for prayers from other believers in his letters, as in Romans 15:30 where he urges them “to strive together with me in your prayers to God on my behalf.” If Paul needed the prayers of other Christians, we certainly need the prayers of our brothers and sisters in faith. The objection that we need only Jesus often reflects an individualistic approach to faith that Scripture does not support.

Mary’s intercessory role has special power because of her unique relationship to Jesus. No human person stands closer to Jesus than his mother, who carried him in her womb, nursed him, raised him, and stood by him even at the cross. The bond between mother and son continues in the heavenly realm where both Mary and Jesus now dwell. Jesus, who perfectly kept the commandment to honor father and mother, continues to honor his mother in heaven. The wedding at Cana shows Jesus responding to Mary’s intercession even before his hour had officially come. Mary’s request moved Jesus to reveal his glory through his first sign. This pattern of Jesus responding to his mother’s requests provides confidence that he continues to hear her prayers for us. Mary’s intercession is powerful not because she constrains Jesus or forces his hand, but because her will is perfectly aligned with his. She prays only for what accords with God’s plan and purpose. Her prayers are effective because they express perfect love and perfect faith. Asking Mary to pray for us means entrusting our needs to the one who knows Jesus most intimately in his humanity and who loves us with a mother’s heart. The Church has experienced the power of Mary’s intercession throughout its history, giving testimony to what Scripture suggests about her continuing role.

Mary’s Assumption and Glorification

The Catholic dogma of the Assumption teaches that Mary was taken up body and soul into heavenly glory at the end of her earthly life. While this doctrine was not formally defined until 1950, belief in Mary’s assumption dates back to the early centuries of Christianity. The dogma states that Mary, “having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory,” as Pope Pius XII declared. This belief flows logically from the doctrines of Mary’s Immaculate Conception and perpetual virginity. If Mary was preserved from original sin and remained sinless throughout her life, she would not be subject to the corruption of the tomb that results from sin. Paul writes in Romans 6:23 that “the wages of sin is death,” connecting bodily death and corruption to sin. Mary’s freedom from sin suggests freedom from its consequences. The Assumption represents God’s vindication of Mary’s faithfulness and the fulfillment of the promise that all believers will be raised and glorified. Mary’s assumption anticipates the resurrection of all the faithful, making her the first fruits of redemption after Christ himself.

Scripture does not explicitly describe Mary’s assumption, but it provides theological foundations for understanding this mystery. The Book of Revelation presents in Revelation 12:1 the vision of a woman “clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars.” While this image has multiple layers of meaning, the Church has traditionally seen Mary represented here in her glorified state. The woman gives birth to the male child who will rule all nations, clearly referring to Christ. Her glorification with heavenly garments and crown suggests her exalted state in heaven. The Psalms speak of the queen standing at the king’s right hand in gold of Ophir in Psalm 45:9, an image applied to Mary as the Queen Mother of the messianic King. The pattern of assumption appears elsewhere in Scripture with Enoch, who was taken up so that he did not see death according to Genesis 5:24 and Hebrews 11:5. Elijah was taken up to heaven in a whirlwind as described in 2 Kings 2:11. These biblical precedents show that God can and does take faithful servants into heavenly glory without leaving their bodies to decay in the grave. Mary’s assumption follows this pattern while exceeding these Old Testament types.

Mary’s assumption body and soul into heaven completes her participation in Christ’s victory over sin and death. The resurrection of the body is a central Christian hope expressed throughout the New Testament. Paul writes extensively about the resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15, explaining that Christ’s resurrection is the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep. Just as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ. Jesus promises in John 6:40 that “everyone who looks on the Son and believes in him should have eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day.” The general resurrection will occur at Christ’s second coming, but Mary’s assumption represents a special anticipation of this universal hope. Her assumption does not make Mary divine or equal to Christ, whose resurrection occurred by his own divine power. Mary was assumed into heaven by God’s power, taken up as a pure gift of grace. Her glorification testifies to the destiny that awaits all the faithful. Catholic theology sees Mary as the image of what the Church will become when Christ returns in glory. She is the icon of the end times, showing in herself what redemption accomplishes.

The silence of Scripture about Mary’s death and what happened to her body provides space for the tradition of the assumption to develop. The New Testament focuses on the apostolic ministry and the early spread of the Gospel rather than providing biographies of all the key figures. We have no biblical account of the deaths of most apostles, but this does not mean their deaths did not occur or were unimportant. Mary’s death, or dormition as the Eastern Church calls it, presumably occurred in the presence of some apostles or disciples who would have cared for her body. The fact that no church claimed to possess Mary’s bodily remains from the earliest times, unlike the veneration of apostolic relics, suggests that the early Christians understood something different had happened with Mary. The tradition of the assumption filled this silence with an understanding that fit the overall biblical teaching about Mary’s role and dignity. Belief in the assumption became universal in Christian tradition long before it was formally defined as dogma. The doctrine represents the Church’s reflection on what Scripture implies about Mary’s final destiny. Her assumption body and soul into heaven crowns her earthly life and confirms her unique participation in Christ’s redemptive work.

Mary’s Queenship and Her Role in Salvation History

The Catholic tradition honors Mary as Queen of Heaven and Earth, a title that reflects her unique relationship to Christ the King. This queenship flows from her divine maternity and her participation in Christ’s saving work. In the ancient kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the queen mother held a position of honor and influence at the king’s court. The king’s mother, rather than his wife or wives, served as the great lady of the kingdom. We see this pattern in 1 Kings 2:19 when Bathsheba approaches King Solomon, who has a throne brought for his mother and seats her at his right hand. The queen mother could bring petitions to the king and intercede on behalf of the people. This Old Testament institution provides the background for understanding Mary’s queenship. She is the mother of the King of Kings, seated in honor in the heavenly kingdom. Her queenship does not mean she rules over Christ or independently of him. She reigns as queen mother in the kingdom of her son. Her royal dignity comes entirely from her relationship to Christ and her role in salvation history.

The biblical basis for Mary’s queenship includes both explicit texts and typological connections. The vision in Revelation 12:1 of the woman clothed with the sun and crowned with twelve stars presents Mary in royal imagery. The crown suggests her queenly status in heaven. Gabriel’s announcement to Mary in Luke 1:32-33 that her son would receive “the throne of his father David” and reign over the house of Jacob forever establishes Jesus’s royal identity. Mary’s position as mother of this eternal King makes her the queen mother of his kingdom. The Magnificat reveals Mary’s awareness of her role in God’s royal plan, as she declares that the Mighty One has done great things for her. Elizabeth greets Mary as “the mother of my Lord,” using royal language. These texts, read together with the Old Testament background of the queen mother’s role, support the understanding of Mary as queen. Her queenship represents not worldly power but spiritual dignity and intercessory authority. She reigns by serving and interceding, bringing the needs of God’s people to her son the King.

Mary’s cooperation with God’s plan of salvation gives her a unique role that justifies calling her queen. God chose to accomplish the Incarnation through Mary’s free consent rather than apart from human cooperation. Her yes to Gabriel’s announcement made possible the coming of the Savior into the world. This cooperation continued throughout her life as she raised Jesus, stood by him in his public ministry, and remained faithful even at the cross. Mary united her will perfectly with God’s will, accepting the sword of sorrow that Simeon predicted would pierce her heart. Her suffering at the foot of the cross united her to Christ’s redemptive sacrifice in a unique way. While Mary did not merit salvation for us, which Christ alone accomplished, she participated in the application of redemption as the spiritual mother of all believers. Her ongoing intercessory role in heaven continues her cooperation with God’s saving work. The title of queen expresses the honor due to one who played such a role in salvation history. Mary’s queenship reminds us that God works through human persons and honors those who faithfully cooperate with divine grace.

Honoring Mary as queen does not diminish Christ’s unique kingship or divinity. Jesus Christ is Lord of lords and King of kings, the eternal Son who rules with the Father and the Spirit. His kingship comes from his divine nature and his victory over sin and death. Mary’s queenship is always derivative, coming from her relationship to Christ and her participation in his mission. Catholic teaching maintains a clear distinction between the worship due to God alone and the honor given to Mary and the saints. The Greek terms latria for worship and dulia for honor express this distinction. Mary receives hyperdulia, a higher form of honor than other saints, but never the worship reserved for God. Her queenship means that she holds the highest place among created beings, not that she somehow shares divinity. The honor given to Mary ultimately glorifies God, who accomplished such great things in her and through her. When we recognize Mary as queen, we praise God’s wisdom in choosing her and God’s grace in sanctifying her. Her exaltation demonstrates what God’s transforming love can accomplish in a human person who fully cooperates with grace. Mary’s queenship points beyond herself to the King she serves and to the kingdom she helps build through her intercession.

Responding to Common Protestant Objections About Marian Doctrine

Many sincere Christians struggle with Catholic teaching about Mary, concerned that it goes beyond or even contradicts Scripture. The objection that Catholics worship Mary represents perhaps the most serious misunderstanding of actual Catholic teaching and practice. The Catholic Church has always taught clearly that worship belongs to God alone, as affirmed in the First Commandment. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states explicitly that the Church’s devotion to Mary “differs essentially from the adoration which is given to the incarnate Word and equally to the Father and the Holy Spirit” and that this devotion “finds expression in liturgical feasts dedicated to the Mother of God and in Marian prayer” (CCC 971). Catholics do not pray to Mary in the sense of offering her worship or believing she has power to answer prayers by her own authority. Prayer in Catholic usage can mean simply speaking to or addressing someone, as when we might say we pray someone will have a safe journey. When Catholics pray to Mary, they ask her to intercede with God on their behalf. The Ave Maria or Hail Mary prayer ends with the words “pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death,” clearly asking for her prayers rather than offering her worship. This distinction between worship of God and honor of the saints remains fundamental to Catholic teaching and practice.

The objection that Marian devotion takes away from Christ’s unique role as mediator deserves careful consideration. Paul writes in 1 Timothy 2:5 that “there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” This text affirms the unique mediation of Christ, who alone reconciled humanity to God through his death and resurrection. Mary’s role as mediatrix, to use traditional Catholic terminology, does not contradict or diminish Christ’s unique mediation. Rather, Mary’s mediation is subordinate to and dependent on Christ’s. She does not mediate between humanity and God independently of her son. Instead, she participates in Christ’s mediation through her intercession, just as all Christians participate in some way when they pray for one another. The Catechism carefully explains that Mary’s mediation flows from Christ’s and “in no way obscures or diminishes this unique mediation of Christ, but rather shows its power” (CCC 970). Her role as mediatrix means that she brings our prayers to Christ and obtains graces from him for us. This understanding preserves Christ’s unique role while acknowledging Mary’s continuing care for believers. The objection often assumes that honoring Mary somehow competes with honoring Christ, but Catholic teaching sees these as complementary rather than contradictory.

Some Protestants object that calling Mary ever-virgin contradicts the biblical references to Jesus’s brothers and sisters. The Gospels mention Jesus’s brothers in passages like Matthew 13:55, which names James, Joseph, Simon, and Judas as his brothers. These texts seem to indicate that Mary had other children after Jesus. However, careful examination of the biblical and historical evidence supports the Catholic understanding of Mary’s perpetual virginity. The Greek word adelphoi translated as “brothers” can refer to various close relatives, not just siblings from the same mother. Neither Hebrew nor Aramaic, the languages Jesus and his family would have spoken, had separate words for cousin, nephew, or other male relatives, using the word for brother in these cases as well. The Septuagint translation of the Old Testament uses adelphos for close relatives who were not literal brothers, as when Lot is called Abraham’s brother in Genesis 14:14 even though Lot was actually Abraham’s nephew. The Gospels never identify Mary as the mother of James, Joseph, Simon, or Judas, which would be natural if they were Jesus’s brothers from the same mother. James and Joseph are identified elsewhere as sons of a different Mary. The New Testament distinguishes between the brothers of Jesus and the apostles, suggesting they were relatives but not part of the immediate family.

The strongest biblical argument for Mary’s perpetual virginity comes from Jesus’s words from the cross entrusting Mary to the beloved disciple. In John 19:26-27, Jesus says to Mary, “Woman, behold your son,” and to the disciple, “Behold your mother.” From that hour, the beloved disciple took Mary into his home. This action makes little sense if Mary had other sons who would have the natural responsibility to care for her. The eldest son remaining would have the duty to care for his widowed mother. That Jesus entrusts Mary to John suggests she had no other children to care for her. This detail, combined with the linguistic evidence about the term “brothers,” supports the traditional understanding of Mary’s perpetual virginity. The early Church universally taught this doctrine from at least the second century, indicating it was part of apostolic tradition. The question of Mary’s virginity after Jesus’s birth matters because it reflects her complete consecration to her unique vocation as Mother of God. Her perpetual virginity signifies the total dedication of her life to Christ. This teaching does not denigrate marriage or sexuality, which are good gifts from God, but rather recognizes that Mary’s calling was singular and required complete dedication.

Protestant concerns about adding to Scripture deserve respectful consideration and honest response. The Catholic Church does not claim to add new revelations to the deposit of faith that closed with the apostolic age. Rather, Catholic doctrine represents the Church’s growing understanding of truths already present in Scripture and apostolic tradition. The development of doctrine involves making explicit what was implicit, drawing out implications of revealed truth under the Spirit’s guidance. The canon of Scripture itself was determined by the Church through a process that took several centuries and involved tradition alongside the biblical texts. The New Testament nowhere provides a table of contents listing which books belong in the Bible. Christians relied on the Church’s authority to determine the canon, demonstrating that Scripture and tradition work together rather than in opposition. The Protestant principle of sola scriptura creates practical difficulties since Christians must interpret Scripture, and different interpretations lead to contradictory conclusions. The Catholic approach sees the Church as the authentic interpreter of Scripture, guided by the Holy Spirit according to Christ’s promise in John 16:13. This interpretive authority prevents Scripture from becoming a source of endless division. Catholics believe that reading Scripture within the living tradition of the Church honors the way God has actually worked in history.

Mary in the Life of the Church and Individual Believers

Devotion to Mary has characterized Catholic life throughout the Church’s history, from the ancient liturgies to modern popular piety. The earliest Christian prayer to Mary that survives, the Sub Tuum Praesidium, dates to the third century and calls upon Mary’s protection. The Church has celebrated feasts honoring Mary from the early centuries, including the Annunciation, the Nativity of Mary, and later the Assumption and Immaculate Conception. The rosary developed in the Middle Ages as a way for ordinary people to meditate on the mysteries of Christ’s life while praying the Hail Mary. This devotion combines vocal prayer with contemplative meditation on Scripture. The Angelus prayer, traditionally prayed three times daily, recalls the Incarnation and Mary’s role in God’s saving plan. Shrines dedicated to Mary draw millions of pilgrims annually, from Guadalupe in Mexico to Lourdes in France to Fatima in Portugal. These devotions express the Church’s love for Mary and confidence in her intercession. They also serve to keep believers focused on Christ by meditating on his life through Mary’s eyes. Marian devotion at its best leads to deeper love for Jesus and more faithful living of the Gospel.

The Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, devoted an entire chapter to Mary, presenting her as the model and mother of the Church. The Council taught that Mary “is endowed with the high office and dignity of being the Mother of the Son of God, by which account she is also the beloved daughter of the Father and the temple of the Holy Spirit” (CCC 966). This teaching locates Mary’s role within the broader context of the Church’s life and mission. Mary is not separate from the Church but the preeminent member of the Church, the one who most fully responded to God’s grace. She models for all believers what it means to hear God’s word and keep it. Her faith, hope, and charity set the pattern for Christian discipleship. The Council also emphasized that Mary’s role continues in heaven, where she watches over the Church with maternal care. Her example and intercession guide the Church through history toward its final goal of union with Christ. Understanding Mary’s relationship to the Church helps believers appreciate how she relates to each individual member as well.

Personal devotion to Mary enriches individual spiritual life by providing a model of holiness and a source of maternal comfort. Many saints throughout Church history have credited their devotion to Mary as central to their spiritual development. Mary’s example of faith shows believers how to trust God even when his plans seem impossible or frightening. Her humility teaches the importance of seeing ourselves accurately before God, neither exaggerating our merits nor despairing of God’s grace. Her obedience demonstrates the freedom that comes from aligning our will with God’s will. Her suffering at the cross shows how to remain faithful through trials and sorrows. Her joy in the Magnificat reveals the proper response to God’s blessings. Meditating on Mary’s life and virtues through the rosary or other devotions helps believers grow in these same virtues. Many people also experience Mary’s maternal care in times of difficulty, finding comfort in prayers to the Mother of God. Her intercession has been credited with countless graces, conversions, healings, and rescues throughout history. These experiences of Mary’s maternal love help believers understand God’s providential care expressed through the communion of saints.

Balanced Marian devotion maintains proper perspective by always relating Mary to Christ and the Trinity. Devotion becomes unbalanced when it treats Mary as an end in herself rather than as one who always points to her son. The true purpose of honoring Mary is to glorify God for the great things accomplished in her and through her. Genuine Marian devotion increases love for Jesus rather than competing with it. The test of authentic devotion is whether it leads to more faithful Christian living, greater participation in the sacramental life of the Church, and deeper charity toward others. Excessive sentimentality or superstitious practices sometimes creep into popular devotion, but these represent distortions rather than the essence of Catholic Marian teaching. The Church guides believers toward devotions rooted in Scripture and tradition, integrated with the liturgical life of the Church. The Catechism teaches that all devotions “should be so drawn up that they harmonize with the liturgical seasons, accord with the sacred liturgy, are in some fashion derived from it, and lead the people to it” (CCC 1675). This principle ensures that Marian devotion supports rather than replaces the central elements of Catholic worship. When practiced properly, devotion to Mary enriches the whole Christian life and strengthens the bonds of communion within the Body of Christ.

Finding Common Ground While Respecting Differences

The differences between Protestant and Catholic understandings of Mary reflect deeper theological disagreements about authority, tradition, and the nature of the Church. These differences developed over centuries and will not disappear quickly or easily. However, both Catholics and Protestants can find common ground in what Scripture clearly teaches about Mary. All Christians can agree that Mary was chosen by God for a unique and essential role in salvation history. Her yes to Gabriel’s announcement made the Incarnation possible in the way God chose to accomplish it. Mary’s faith and obedience provide an example for all believers to follow. Her words at Cana, “Do whatever he tells you,” express the heart of Christian discipleship. Both Catholic and Protestant Christians honor Mary as blessed among women and as the Mother of Jesus. These shared convictions provide a foundation for respectful dialogue about areas of disagreement. Understanding the biblical texts carefully and charitably considering how others interpret them can reduce unnecessary conflict. The goal should be seeking truth together rather than simply defending established positions.

Catholics can understand Protestant concerns about Marian devotion by recognizing how it might appear to outsiders. When Protestants see Catholics praying before statues of Mary, they may genuinely worry about idolatry. Catholics can explain that images serve as reminders and aids to devotion rather than as objects of worship themselves. The practice of asking Mary to pray for believers can seem strange to those unfamiliar with the communion of saints. Catholics can clarify that they ask Mary’s prayers just as they might ask a friend on earth to pray for them. The titles given to Mary may sound excessive or unbiblical to Protestant ears. Catholics can explain the theological reasoning behind terms like Mother of God and show how they protect essential truths about Christ. Building understanding requires patience and willingness to see how Catholic practices might be misunderstood. Catholics should also acknowledge when popular devotions sometimes become unbalanced or when believers might not fully understand the theology behind the practices. Humble dialogue serves truth better than defensive arguments.

Protestants can benefit from examining the biblical and historical evidence for Catholic Marian teaching with fresh eyes. The fact that the earliest Christians honored Mary and developed devotions to her provides important context for understanding the biblical texts. The liturgies and writings of the early Church show how Christians read Scripture in community rather than as isolated individuals. Protestant scholars increasingly recognize the value of tradition and the problems with a strictly individualistic approach to biblical interpretation. The five solas of the Reformation expressed important theological principles, but they do not exhaust Christian truth. Exploring what the Church Fathers taught about Mary can help Protestants see that Catholic doctrine did not arise from nowhere centuries after Christ. The development of Marian doctrine follows patterns consistent with how other Christian doctrines developed. Protestants might also consider whether their reaction against Catholic practices has led to neglecting biblical teaching about Mary. Finding balance requires avoiding both excessive elaboration and inadequate attention to what Scripture reveals.

The unity that Christ desires for his followers requires mutual respect and honest engagement with differences. Jesus prayed in John 17:21 that all his disciples would be one so that the world would believe. The divisions among Christians weaken the Church’s witness and hinder the spread of the Gospel. While unity does not mean pretending that differences do not exist, it does require treating one another with charity. Catholics and Protestants can work together on many areas of Christian life and witness while honestly discussing areas of disagreement. The question of Mary’s role remains significant, but it need not prevent cooperation in serving the poor, defending life, and proclaiming Christ. Both traditions can learn from each other’s strengths while gently addressing weaknesses. Catholics can appreciate Protestant emphasis on Scripture and personal relationship with Jesus. Protestants can appreciate Catholic sacramental life and connection to historical tradition. The conversation about Mary can become an opportunity for deeper understanding rather than a source of division. Reading Scripture together and praying together builds relationships that make honest dialogue possible. The Holy Spirit continues to work in all Christians, leading toward the unity Christ desires.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.