Brief Overview

- The claim that the pope is the Antichrist arose during the Protestant Reformation as a means to justify separation from the Catholic Church.

- The term “antichrist” appears only four times in Scripture, exclusively in the letters of John, and refers to those who deny that Jesus Christ came in the flesh.

- Catholic teaching affirms that the pope is the successor of Saint Peter and serves as the visible head of the Church on earth.

- Early Church Fathers, including Irenaeus and Hippolytus, described the Antichrist as a future political ruler who would rebuild the Jewish temple and claim to be the Messiah himself.

- The papal office exists precisely to affirm that Christ has come in the flesh and now reigns in heaven, making the accusation contradictory to biblical descriptions of antichrist.

- A careful reading of Scripture reveals that the characteristics attributed to the Antichrist in biblical texts do not align with the papacy or its historical function in Christianity.

Understanding the Biblical Concept of Antichrist

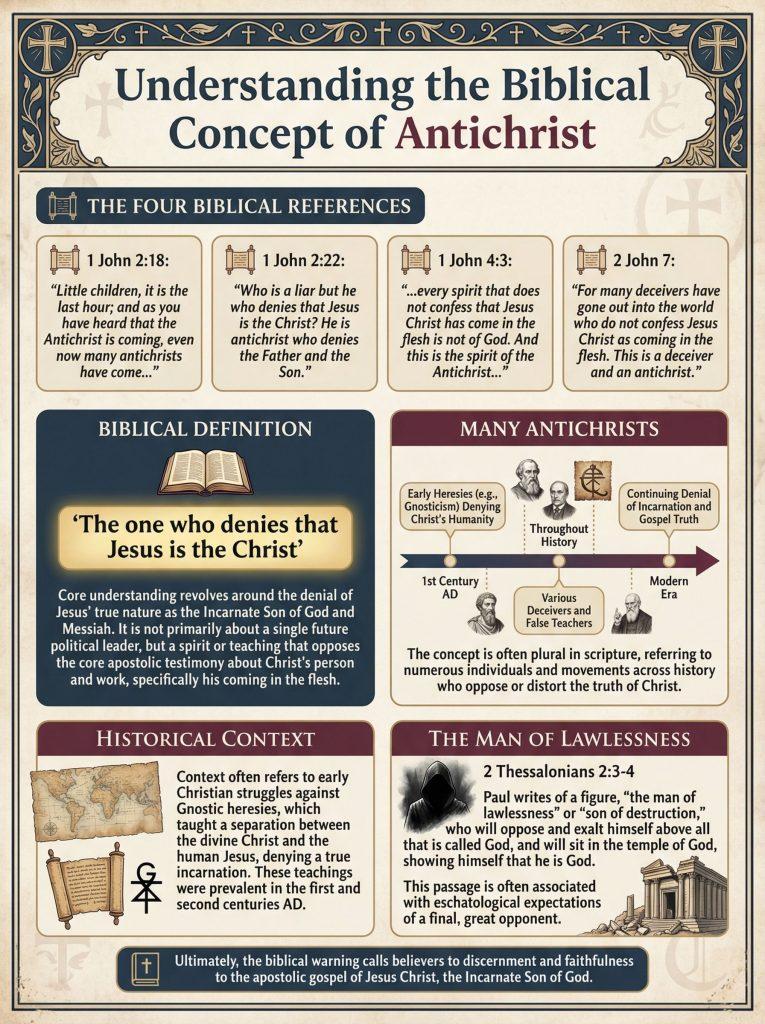

The word “antichrist” appears in only four verses of Sacred Scripture, and all of these verses are found in the epistles of Saint John. These passages include 1 John 2:18, 1 John 2:22, 1 John 4:3, and 2 John 7. This limited usage is significant because it provides a clear and focused biblical definition of what constitutes an antichrist. In 1 John 2:18, John writes to the early Christian community about both a coming antichrist and many antichrists who are already present in the world. This indicates that the concept of antichrist is not limited to a single individual but includes anyone who opposes Christ in specific ways. The apostle clarifies this definition in 1 John 2:22 by stating that the antichrist is the one who denies that Jesus is the Christ. This denial is not merely intellectual but represents a fundamental rejection of Christ’s identity and mission. Saint John further explains in 1 John 4:3 that every spirit that does not confess Jesus is not from God, and this is the spirit of the antichrist. Finally, in 2 John 7, he writes that many deceivers have gone out into the world who do not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, and such a person is the deceiver and the antichrist.

The biblical definition provided by Saint John is remarkably consistent across all four passages. The essential characteristic of an antichrist is the denial that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh. This denial takes on various forms, including rejecting Jesus as the Messiah, refusing to acknowledge his divine nature, or denying the reality of the Incarnation. The early Church understood this teaching to be directed primarily against Gnostic heresies that denied the physical reality of Christ’s human nature. These heretics claimed that Jesus only appeared to have a physical body but was actually a purely spiritual being. Such teaching undermined the entire foundation of Christian faith because it made the Crucifixion and Resurrection meaningless. If Christ did not truly take on human flesh, suffer, die, and rise again in a real body, then salvation itself becomes impossible. The apostle John wrote his letters specifically to combat these dangerous teachings and to preserve authentic Christian faith. His identification of antichrists with those who deny the Incarnation provides a clear standard by which to evaluate any claim that a particular person or institution fulfills this prophetic role.

The Catholic Church’s teaching about the papacy stands in direct opposition to the characteristics John attributes to antichrists. The entire basis for the papal office rests on the confession that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, lived among us, died for our sins, and rose from the dead in a glorified body. Every pope throughout history has been required to profess the Apostles’ Creed, which explicitly states that Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. This creed continues by affirming that he descended to the dead, rose again on the third day, and ascended into heaven. The pope’s primary function is to preserve and proclaim this apostolic faith, not to deny it. In fact, the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches extensively about the Incarnation and the necessity of confessing Christ’s coming in the flesh. The papal office exists precisely because Christ came in the flesh, established his Church on earth, and then ascended to heaven, leaving Peter and his successors as his vicars or representatives until his return in glory.

When examining the broader biblical context, additional passages shed light on the concept of the Antichrist, though they do not use that specific term. Saint Paul writes in 2 Thessalonians 2:3-4 about the man of lawlessness, the son of destruction, who opposes and exalts himself against every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God. This passage is often associated with the Antichrist figure and provides additional details about his character and actions. The man of lawlessness will claim to be God himself, not merely God’s representative on earth. He will sit in the temple of God, which the early Fathers understood to mean the Jewish temple in Jerusalem that would be rebuilt. This figure represents total rebellion against God and complete rejection of all divine authority. The pope, by contrast, never claims to be God but instead claims to be the servant of the servants of God, a title that emphasizes humility and service rather than self-deification. The papal office is fundamentally different from the self-exaltation Paul describes because the pope points people toward Christ rather than toward himself.

The Book of Revelation presents various images that have been interpreted in connection with the Antichrist, though again the term itself does not appear in this book. Revelation speaks of beasts, false prophets, and figures who deceive the nations and lead people away from worship of the true God. These symbolic images have been understood in multiple ways throughout Christian history, with different interpreters applying them to various historical figures and institutions. However, the consistent theme throughout Revelation is opposition to Christ and his Church through deception, persecution, and false worship. The Catholic understanding of these passages sees them as warnings about threats that can arise in any age, rather than specific predictions about the papacy. The early Church Fathers, who lived much closer to the time of the apostles and had a better understanding of their intended meaning, never interpreted these passages as referring to the bishop of Rome. Instead, they saw them as warnings about future persecutions and trials that the Church would face throughout history.

The concept of “many antichrists” mentioned by John in 1 John 2:18 suggests that the spirit of antichrist manifests in various ways throughout history rather than being limited to one final figure. John tells his readers that they can know it is the last hour because many antichrists have already come. This indicates that the presence of antichrists is a sign of the end times, which from the apostolic perspective began with Christ’s first coming. The Church has existed in the last days since Pentecost, and throughout this entire period, various individuals and movements have embodied the spirit of antichrist by denying essential Christian teachings about Jesus. These might include heretics who denied Christ’s divinity, false teachers who led people away from the faith, or persecutors who attempted to destroy the Church. The Catholic Church has consistently opposed all such manifestations of the antichrist spirit by preserving and defending orthodox Christian teaching. The popes throughout history have called councils, written encyclicals, and exercised their teaching authority specifically to combat heresies that deny fundamental truths about Christ.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church addresses the concept of the Antichrist in its discussion of Christ’s final coming in glory. In sections 675 and 676, the Catechism teaches that before Christ’s second coming, the Church must pass through a final trial that will shake the faith of many believers. This trial will involve the supreme religious deception of the Antichrist, which is described as a pseudo-messianism by which man glorifies himself in place of God and his Messiah who has come in the flesh. The Catechism makes clear that this deception already begins to take shape whenever claims are made to realize within history a messianic hope that can only be realized beyond history through final judgment. This teaching emphasizes that the Antichrist represents human pride and self-worship rather than any legitimate religious authority. The Church recognizes that the spirit of antichrist operates through various movements and ideologies that promise worldly salvation apart from Christ, not through the office instituted by Christ himself to preserve his teachings.

Understanding the biblical concept of antichrist requires careful attention to what Scripture actually says rather than imposing later interpretations onto the text. The consistent witness of the New Testament is that antichrists are those who deny Christ’s coming in the flesh and lead people away from authentic faith in him. This definition cannot be legitimately applied to the papacy, which exists precisely to maintain and proclaim faith in Christ’s Incarnation, death, and Resurrection. The pope’s role as visible head of the Church on earth serves to unify believers around the apostolic faith that has been handed down from the time of Christ and the apostles. Far from denying Christ, the papal office affirms him and points all people toward him as the only Savior and Lord. Any claim that the pope is the Antichrist must ignore or distort the clear biblical definition provided by Saint John and must overlook the actual function and teaching of the papacy throughout Christian history.

Historical Origins of the Anti-Papal Interpretation

The identification of the pope as the Antichrist did not originate in apostolic times or in the early Church but arose during the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. This claim served a specific purpose for the reformers who sought to justify their break from the Catholic Church and to delegitimize papal authority. Martin Luther, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, and John Knox all identified the pope as the Antichrist in their writings and confessional documents. The Lutheran Book of Concord explicitly states that the pope is the real Antichrist who has raised himself over and set himself against Christ. Similarly, the Westminster Confession, which was adopted by Presbyterian and Anglican communities, declares that there is no other head of the Church but Jesus Christ and that the pope is that Antichrist, that man of sin, and that son of perdition who exalts himself in the Church against Christ. These statements reveal the polemical nature of the accusation, which was designed to rally opposition to Rome and to provide theological justification for the establishment of separate Protestant churches.

The reformers needed to explain why they were leaving what had been considered the one, holy, catholic Church for more than a millennium. If the Catholic Church was simply mistaken on certain doctrinal points, reformation from within might have been sufficient. However, if the very head of that Church was the Antichrist himself, then separation became not merely justified but necessary for salvation. This rhetorical strategy helped to consolidate Protestant identity and to maintain separation from Rome even when political and social pressures might have favored reunion. The anti-papal interpretation of Antichrist texts served an important function in Protestant self-understanding and apologetics. By identifying the papacy with the ultimate enemy of Christ prophesied in Scripture, Protestant leaders could present themselves as faithful Christians fighting against apostasy rather than as schismatics dividing Christ’s Church. This interpretation also allowed them to portray their movement as fulfilling biblical prophecy rather than as a novel development in Christian history.

The specific arguments used by Protestant reformers to identify the pope as the Antichrist often involved creative reinterpretation of biblical texts. They claimed that the temple of God mentioned in 2 Thessalonians 2:4, where the man of lawlessness sits proclaiming himself to be God, referred to the Vatican or to St. Peter’s Basilica rather than to the Jewish temple in Jerusalem. This reinterpretation was necessary because the pope obviously does not sit in the Jewish temple. They also argued that papal claims to exercise authority over the Church constituted the self-exaltation Paul describes, even though such claims differ fundamentally from claiming to be God oneself. Protestant interpreters pointed to various papal teachings and practices they considered unbiblical as evidence of the Antichrist’s deception. However, these arguments required ignoring or dismissing the consistent testimony of the early Church Fathers about the nature and identity of the Antichrist.

The early Church Fathers, who lived much closer in time to the apostles and who had a better understanding of first-century context and language, never identified the bishop of Rome as the Antichrist. Instead, their writings present a remarkably different picture of this figure. Church Fathers such as Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Tertullian, Cyprian, Lactantius, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Augustine all wrote about the Antichrist, and their descriptions share common elements that distinguish this figure from the papacy. They consistently described the Antichrist as a future political ruler who would arise in the context of the Roman Empire or its successor states. This figure would be a king who would claim absolute power and would demand worship as God himself. Many Fathers believed he would be Jewish, possibly from the tribe of Dan, and would deceive the Jewish people by fulfilling their expectations for a political Messiah. The Antichrist would rebuild the temple in Jerusalem and present himself as the long-awaited Messiah of Israel, gaining the allegiance of many Jews before revealing his true nature.

Irenaeus, writing in the late second century, explained that the Antichrist would be endued with all the power of the devil and would come as an impious, unjust, and lawless ruler rather than as a legitimate king in subjection to God. He would set aside idols to persuade people that he himself is God, raising himself up as the only idol. Irenaeus specifically mentions that this figure would sit in the temple at Jerusalem, referring to the physical temple that would be rebuilt. He taught that the Antichrist would reign for three years and six months before being destroyed by Christ’s second coming. This description clearly refers to a political and military ruler rather than to a religious leader who claims to represent Christ. Hippolytus, writing in the early third century, provided even more specific details. He taught that the Antichrist would come from the tribe of Dan and would work signs and wonders to deceive people. Hippolytus emphasized that the Antichrist would especially love the nation of the Jews and would build the temple in Jerusalem for them. He would claim to be the Messiah promised to Israel rather than claiming to be the vicar of Jesus Christ.

These patristic descriptions of the Antichrist are irreconcilable with the Protestant claim that the pope fulfills this role. The pope does not come from the tribe of Dan but is typically of European origin. He does not rebuild the Jewish temple or present himself as the Jewish Messiah. He does not claim to be God himself but rather claims to be the servant and representative of Christ. He does not persecute the Church but rather leads it. He does not deny that Jesus is the Christ but instead makes this confession the very foundation of his ministry. The early Fathers understood the Antichrist to be a figure who would arise at the end of time to deceive the world through false miracles and to persecute Christians who refused to worship him. This eschatological figure represents the final and most severe trial the Church will face before Christ’s return. The papal office, by contrast, has existed for two thousand years and serves to preserve the Church’s faith and unity rather than to persecute it.

The Protestant interpretation of the Antichrist required not only reinterpreting Scripture but also dismissing or ignoring the entire patristic tradition. The reformers claimed that the early Church had gradually fallen into error and that papal authority represented the culmination of this apostasy. However, this claim faces significant historical problems. The bishop of Rome exercised a unique authority in the Church from the earliest centuries, as evidenced by letters from Clement of Rome in the first century, Irenaeus in the second century, and numerous other early sources. If the papacy itself represented the Antichrist, then Christ’s promise that the gates of hell would not prevail against his Church would have failed. The Church would have been completely overcome by evil within the first few centuries, and authentic Christianity would have ceased to exist until the Protestant Reformation. This scenario contradicts Jesus’s promises about the Church’s indefectibility and the Holy Spirit’s perpetual presence with it.

The anti-papal interpretation of Antichrist prophecies has significantly declined even within Protestant circles in recent centuries. Most modern Protestant scholars recognize that this interpretation was driven more by polemical concerns than by sound biblical exegesis. Many contemporary Protestant denominations have removed such language from their confessional statements or have de-emphasized it in their teaching. Ecumenical dialogues between Catholics and Protestants have fostered better understanding of historical conflicts and have revealed that many of the accusations made during the Reformation period were based on misunderstandings or mischaracterizations of Catholic teaching. While significant theological differences remain between Catholics and Protestants, the rhetoric of identifying the pope as the Antichrist has largely been recognized as unhelpful and unbiblical. This shift represents a return to more careful reading of Scripture and greater appreciation for the witness of the early Church.

The Biblical Foundation of Papal Authority

Understanding why the pope cannot be the Antichrist requires examining the biblical foundation for the papacy and recognizing how this office relates to Christ rather than opposing him. The Gospel of Matthew records a pivotal moment when Jesus asked his disciples who people said he was and then who the disciples themselves believed him to be. Simon Peter responded with the great confession of faith, declaring that Jesus was the Christ, the Son of the living God, as recorded in Matthew 16:16. Jesus’s response to this confession established the foundation for Peter’s unique role among the apostles. In Matthew 16:18-19, Jesus said that Peter was blessed because this truth had been revealed to him by the Father in heaven. Jesus then declared that Peter was the rock upon which he would build his Church and that the gates of hell would not prevail against it. Finally, Jesus promised to give Peter the keys of the kingdom of heaven, with the authority to bind and loose on earth in a way that would be recognized in heaven.

This passage establishes several crucial points about Peter’s role and, by extension, about the papal office. First, Jesus built his Church on Peter specifically in connection with Peter’s confession of faith. This means the Church is founded on both the person of Peter and the faith he professed. The pope’s authority derives from his responsibility to preserve and proclaim this apostolic faith, not from any personal merit or achievement. Second, Jesus promised that the gates of hell would not prevail against the Church built on Peter. This promise of indefectibility means that the Church will never be completely overcome by error or evil, even during times of severe trial or persecution. If the papacy itself were the Antichrist, this promise would be meaningless. Third, the gift of the keys represents real authority to govern the Church and to make decisions that have spiritual consequences. This authority exists to serve the Church’s mission rather than to dominate or destroy it.

The Aramaic wordplay in Jesus’s statement to Peter provides important insight into the meaning of this passage. Jesus said to Simon, “You are Kepha, and on this kepha I will build my Church.” The word “kepha” means rock in Aramaic, the language Jesus spoke. By giving Simon the name Peter, which means rock, and then saying he would build his Church on this rock, Jesus clearly identified Peter himself as the foundation. Some interpreters have tried to argue that Jesus was referring to Peter’s confession of faith rather than to Peter personally, or that Jesus was referring to himself as the rock. However, the grammar and context of the passage make such interpretations difficult to sustain. Jesus was speaking directly to Peter, gave him a new name meaning rock, and then said he would build his Church on “this rock” while continuing to address Peter. The most natural reading is that Jesus designated Peter as the rock foundation of the visible Church on earth.

Additional biblical passages support Peter’s unique role among the apostles. In Luke 22:31-32, Jesus told Peter that Satan had demanded to sift all the disciples like wheat, but that Jesus had prayed specifically for Peter that his faith might not fail. Jesus then commanded Peter to strengthen his brothers once he had turned back. This passage reveals that Peter was given a special responsibility to support and encourage the other apostles, particularly during times of trial. After the Resurrection, Jesus asked Peter three times if Peter loved him, and three times Jesus commanded Peter to feed his sheep, as recorded in John 21:15-17. This threefold commission restored Peter after his threefold denial and established him as the shepherd of Christ’s flock. The imagery of feeding sheep clearly indicates pastoral authority and responsibility for caring for other believers. These passages demonstrate that Peter’s primacy was not invented by later generations but was established by Christ himself during his earthly ministry.

The Acts of the Apostles shows Peter exercising his leadership role in the early Church in various ways. Peter took the initiative in replacing Judas among the Twelve, as described in Acts 1:15-26. On the day of Pentecost, Peter was the one who stood up and addressed the crowd, explaining the meaning of the Holy Spirit’s coming and calling people to repentance, as recorded in Acts 2:14-41. When questions arose about whether Gentiles could be admitted to the Church without first becoming Jews, Peter’s testimony about his vision and his visit to Cornelius played a decisive role in resolving the matter, as described in Acts 10-11 and Acts 15. Peter’s letters, 1 and 2 Peter, were written to strengthen believers and to warn against false teachers. Throughout the Acts of the Apostles, Peter functions as the spokesman and leader of the apostolic community, though this does not diminish the important roles played by other apostles like James and John, or by Paul who was called later.

The Catholic understanding of the papacy teaches that Peter’s role as rock and shepherd did not die with him but continues in his successors. This understanding is rooted in the nature of the Church as a permanent institution that will last until Christ’s return. If Jesus intended his Church to continue throughout history, and if he established Peter as the rock foundation and shepherd of that Church, then Peter’s foundational role must continue in some way. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches in sections 880-882 that Jesus gave the apostles a share in his own mission and authority, and that this apostolic mission was intended to continue until the end of time. The pope, as the bishop of Rome and Peter’s successor, is described in CCC 882 as the perpetual and visible source and foundation of unity for both the bishops and all the faithful. The Roman Pontiff has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, not as a tyrant but as pastor and shepherd serving under Christ who is the invisible head.

This Catholic teaching about papal authority stands in direct opposition to the characteristics of the Antichrist described in Scripture. The pope does not deny that Jesus is the Christ but makes this confession the foundation of his office. He does not claim to be God but claims to be God’s servant. He does not persecute the Church but rather serves it. He does not demand worship for himself but directs worship toward God. The pope’s authority derives entirely from Christ and exists to preserve what Christ taught rather than to replace Christ with himself. Every pope throughout history has professed the same apostolic faith that Peter professed, acknowledging Jesus as the Christ, the Son of the living God. Far from opposing Christ, the papal office exists to ensure that Christ’s teachings are faithfully preserved and transmitted to each new generation of believers. The accusation that the pope is the Antichrist requires ignoring this fundamental reality about the nature and purpose of the papacy.

Catholic Teaching on the True Nature of Antichrist

The Catholic Church’s official teaching about the Antichrist, as expressed in the Catechism and in Church documents, provides a very different understanding from the anti-papal interpretation promoted during the Reformation. The Church teaches that before Christ’s second coming, believers will face a final trial that will test their faith in unprecedented ways, as explained in CCC 675. This trial will involve what the Catechism calls the supreme religious deception, which is the deception of the Antichrist. This deception is described as a pseudo-messianism by which human beings glorify themselves in place of God and in place of God’s Messiah who has come in the flesh. The fundamental character of this deception is human self-worship and the attempt to achieve salvation through human means apart from God’s grace. The Antichrist represents the ultimate expression of human pride and rebellion against God.

The Catechism further explains in CCC 676 that the Antichrist’s deception already begins to take shape in the world whenever people claim to realize within history the messianic hope that can only be fulfilled beyond history through God’s final judgment. This means the spirit of antichrist is present in various ideologies and movements that promise worldly utopia or perfect human society without reference to God or to moral truth. Such movements might include totalitarian political systems that claim absolute authority over human life, secular philosophies that deny objective moral truth, or religious teachings that fundamentally distort the gospel message. The Church has faced various manifestations of this antichrist spirit throughout history, from Roman imperial persecution to modern totalitarian regimes that demand total allegiance. In each case, the Church has resisted by maintaining faith in Christ and refusing to compromise essential Christian teaching.

Catholic tradition distinguishes between the spirit of antichrist, which is active throughout history, and the Antichrist as a specific individual who will appear at the end of time. Saint John speaks of both many antichrists who are already present and the Antichrist who is coming. The Church has always recognized that various heresies, false teachers, and persecutors embody the spirit of antichrist by denying fundamental Christian truths or by opposing the Church’s mission. However, Catholic teaching also acknowledges that Scripture and Tradition point toward a final manifestation of evil in a particular individual who will arise before Christ’s return. This figure will deceive many people through signs and wonders, will claim divine authority for himself, and will lead a final persecution against those who remain faithful to Christ. The Church does not claim to know precisely when this will occur or exactly what form it will take, but maintains vigilance and prepares believers to remain faithful under trial.

The Catholic understanding of the Antichrist is deeply rooted in the patristic tradition. The early Church Fathers consistently taught that the Antichrist would be a political ruler rather than a religious leader. He would arise from the context of worldly kingdoms and would seek political and military power. Lactantius, writing in the early fourth century, described the Antichrist as a king who would arise out of Syria, born from an evil spirit, who would be both overthrower and destroyer of the human race. He taught that this king would constitute himself as God and would order himself to be worshipped as the Son of God. Cyril of Jerusalem, writing in the mid-fourth century, taught that the Antichrist would deceive the Jews through lying signs and wonders of magical deceit until they believed he was the expected Christ. He would then display wicked deeds against all people, especially Christians, before being destroyed by Christ’s second coming after three and a half years of reign.

These patristic descriptions emphasize several key characteristics of the Antichrist. First, he will claim to be the Messiah himself rather than claiming to represent or serve the Messiah. This is fundamentally different from the papal office, which exists to represent Christ who has already come, not to replace him or claim his identity. Second, the Antichrist will use deception and false miracles to gain followers rather than teaching authentic Christian doctrine. The popes throughout history have preserved orthodox teaching even when doing so was unpopular or dangerous. Third, the Antichrist will actively persecute Christians who refuse to worship him or accept his claims. The pope, by contrast, shepherds the Christian community and works to spread the faith rather than persecuting believers. Fourth, the Antichrist’s reign will be relatively brief, lasting three and a half years according to several Church Fathers. The papacy has existed for two millennia, serving the Church throughout that entire period.

Saint Augustine, perhaps the most influential of all the Church Fathers in the Western tradition, wrote extensively about the end times and the Antichrist. In his masterwork, The City of God, Augustine explained that Daniel’s prophecies about the final judgment indicate that the Antichrist will come first and carry on his destruction before the eternal reign of the saints begins. Augustine saw the Antichrist as a specific individual who would be conquered by Christ rather than as an institution or office within the Church. Like other Fathers, Augustine understood the Antichrist to be a political and military figure rather than a religious leader. This patristic consensus carries significant weight because these early writers lived much closer to apostolic times and had a better understanding of what the apostles meant by their prophecies about the Antichrist. Their unanimous witness against identifying any Church office, let alone the papacy, with the Antichrist demonstrates how foreign this interpretation was to early Christian understanding.

The Catholic Church’s teaching about the Antichrist serves practical purposes in the life of believers. By understanding the true nature of this deception, Catholics can recognize and resist various forms of false messianism that arise throughout history. Any ideology or movement that promises perfect human happiness apart from God, any teaching that denies essential Christian truths about Christ, or any power that demands total allegiance and suppresses religious freedom may embody the spirit of antichrist. The Church calls believers to remain faithful to Christ and to his gospel no matter what pressures or persecutions they may face. This vigilance requires knowing what the Church actually teaches and being able to distinguish authentic Christian faith from counterfeits. The pope’s role in this regard is to preserve and teach the apostolic faith so that believers will not be led astray by false teachings.

Catholic teaching also emphasizes hope and confidence in Christ’s ultimate victory over all forms of evil, including the Antichrist. The same passages that warn about coming deception and persecution also promise that Christ will return in glory to judge the living and the dead. The Antichrist, despite his power and deception, will ultimately be defeated by Christ. This victory is certain because it flows from Christ’s Resurrection, which has already broken the power of sin and death. The Church’s mission is to remain faithful until that final victory is fully manifested. The papal office serves this mission by maintaining the Church’s unity and orthodoxy, ensuring that successive generations of believers receive the same faith that was once delivered to the saints. Far from being the Antichrist, the pope serves as a sign of Christ’s continuing care for his Church and his determination to preserve it until his return.

Responding to Common Objections and Misunderstandings

Several specific objections are commonly raised by those who claim the pope is the Antichrist, and each of these objections deserves careful consideration and response. One frequent objection concerns papal titles such as “Vicar of Christ” or “Holy Father,” which critics argue represent blasphemous claims to divine authority. However, understanding the proper meaning of these titles reveals no contradiction with biblical teaching. The term “vicar” simply means representative or substitute, indicating that the pope acts in Christ’s place as the visible head of the Church while Christ is in heaven. This does not mean the pope claims to be Christ or to possess divine attributes, but rather that he has been given authority by Christ to govern the Church in Christ’s name. Jesus himself gave this authority to Peter and the apostles when he said in John 20:21, “As the Father has sent me, even so I send you.” The term “Holy Father” is used as a title of respect for the pope’s office rather than as a claim to be God the Father.

Another common objection involves the ornamentation and ceremonies associated with the papacy, which critics view as evidence of pride and self-exaltation rather than humble service. They point to the elaborate papal vestments, the respect shown to the pope by other Catholics, and the grandeur of Vatican ceremonies as proof that the pope embodies the spirit of the Antichrist. However, this objection confuses appropriate honor given to an office with worship given to God. Throughout Scripture, legitimate authorities are shown proper respect without this constituting idolatry. The ceremonial aspects of the papacy reflect the dignity of the office and the importance of the Church’s mission rather than personal pride. Moreover, many popes throughout history have lived simply despite the ceremonial requirements of their office, and the current emphasis in papal ministry has increasingly focused on simplicity and service to the poor. The external trappings of office do not determine whether someone is the Antichrist; rather, the content of their teaching and the nature of their claims determine this.

Some critics point to historical instances of papal corruption or moral failure as evidence that the papacy is the Antichrist. They cite examples of popes who lived immorally, who engaged in political intrigue, or who made poor decisions in governing the Church. While Catholics acknowledge that some popes throughout history failed to live up to the holiness their office demands, this does not prove the papacy itself is evil or that the pope is the Antichrist. The Church teaches that the pope’s authority to teach infallibly on matters of faith and morals does not depend on his personal holiness but on Christ’s promise to preserve the Church from error. Jesus chose Judas as one of the Twelve despite knowing he would betray him, and Jesus predicted that Peter himself would deny him three times. The presence of sinners within the Church, even in leadership positions, does not negate Christ’s promises or transform the Church into the kingdom of Antichrist. Rather, it demonstrates the Church’s need for ongoing conversion and reform.

The objection that papal teaching contradicts Scripture or adds to biblical revelation requires careful examination. Protestant critics often claim that doctrines such as papal infallibility, Marian dogmas, or the Catholic understanding of the sacraments represent additions to Scripture that fulfill Paul’s prophecy about those who distort the gospel. However, Catholics understand Church teaching as the authentic interpretation of Scripture and Tradition rather than as additions to divine revelation. The Church existed before the New Testament was written, and the apostles passed on their teaching both through written documents and through oral tradition. The Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 demonstrates that the apostles exercised teaching authority to resolve disputed questions, and this authority continues in their successors. When the pope defines a doctrine infallibly, he is not creating new revelation but clarifying what has always been believed and taught by the Church. The development of doctrine represents deeper understanding of revealed truth rather than contradiction of it.

Some critics argue that the Catholic Church’s exercise of temporal power throughout history proves it embodies the Antichrist’s political ambitions. They point to periods when popes governed the Papal States, involved themselves in European politics, or called for crusades against various enemies. While acknowledging that the Church’s involvement in temporal affairs has sometimes been excessive or misguided, Catholics distinguish between the essential spiritual mission of the papacy and the contingent historical circumstances in which popes have operated. The Church exists within history and must engage with political realities to carry out its mission, but this does not mean political power is essential to papal office. In recent centuries, the loss of the Papal States has actually clarified the essentially spiritual nature of papal authority. The pope today exercises moral authority rather than political power, speaking on behalf of justice and human dignity without commanding armies or governing territories.

The claim that Catholic liturgy and sacraments represent the “abomination of desolation” mentioned in Matthew 24:15 reflects fundamental misunderstanding of both biblical prophecy and Catholic worship. Jesus was referring to Daniel’s prophecy about pagan desecration of the Jerusalem temple, which was fulfilled when Roman armies destroyed the temple in 70 AD. Catholic liturgy, by contrast, worships the one true God through Jesus Christ in union with the Holy Spirit. The Mass is not an abomination but the re-presentation of Christ’s one sacrifice on Calvary, making that sacrifice present for believers today. The sacraments are means of grace instituted by Christ himself, not inventions of the Antichrist. This objection reveals the depth of misunderstanding that can result from reading Scripture through the lens of anti-Catholic prejudice rather than allowing Scripture to speak for itself.

Perhaps the most fundamental problem with identifying the pope as the Antichrist is that this claim requires believing that Christ’s Church was completely overcome by evil within the first few centuries of its existence. If the papacy, which has existed since apostolic times, is the Antichrist, then Christ’s promise that the gates of hell would not prevail against his Church has failed. The Church would have fallen into complete apostasy, leaving no authentic Christian community on earth for more than a millennium. This scenario contradicts Jesus’s promises about the Church’s indefectibility and the Holy Spirit’s perpetual presence with believers. It also raises the question of how the Protestant Reformers could have access to authentic Christian teaching if the Church had been completely corrupted. They relied on Scripture that had been preserved by this supposedly apostate Church and on theological concepts that had been developed within the Christian tradition. The very idea that they could reform Christianity presupposes that some authentic Christianity had survived to be reformed.

The Witness of Scripture Rightly Interpreted

When Scripture is read carefully and in context, it becomes clear that the papal office does not fulfill biblical descriptions of the Antichrist. The letters of John provide the clearest biblical definition of antichrist, and this definition centers on denial that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh. Every pope throughout history has confessed that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God, who came in the flesh, died for our sins, and rose from the dead. This confession is the very foundation of the papal office and the reason for its existence. The pope’s primary responsibility is to preserve and proclaim this apostolic faith, not to deny it. Any claim that the pope is the Antichrist must ignore or distort John’s explicit definition in favor of later, politically motivated interpretations that lack biblical support.

Paul’s description of the man of lawlessness in 2 Thessalonians 2 emphasizes self-deification and absolute lawlessness rather than religious leadership or teaching authority. The man of lawlessness will exalt himself above every so-called god and will sit in God’s temple proclaiming himself to be God. The pope does not claim to be God but claims to serve God as the vicar of Christ. He does not sit in the Jewish temple claiming divine honors but resides in Rome as bishop of that ancient Christian community. He does not oppose all worship and religious practice but rather promotes authentic worship of the true God. The characteristics Paul attributes to the man of lawlessness simply do not match the reality of the papal office. Paul also emphasizes that this figure will be revealed at the proper time and will be destroyed by Christ’s return; the papacy has existed for two thousand years and serves the Church’s mission rather than opposing it.

The Book of Revelation, while it does not use the term “antichrist,” presents various figures who oppose Christ and deceive the nations. These symbolic visions have been interpreted in many different ways throughout Christian history. However, the consistent theme is opposition to Christ and persecution of his followers. The early Church Fathers understood these visions primarily in terms of Roman imperial persecution, though they also saw them as having ongoing relevance for future trials the Church would face. The Catholic Church has experienced periods of fierce persecution throughout its history, but in none of these cases has the persecution come from the papal office itself. Rather, popes have often been martyred for their faith or have stood firm against persecuting powers. The witness of martyred popes like Peter, Clement, and many others throughout history demonstrates that the papacy has suffered persecution rather than inflicting it on faithful Christians.

Jesus’s teachings about false prophets and false messiahs provide additional criteria for recognizing deception. In Matthew 24:24, Jesus warned that false messiahs and false prophets would arise and perform great signs and wonders to lead people astray if possible, even the elect. The key characteristic of these deceivers is that they claim to be the Messiah or prophets of a new revelation. The pope makes no such claim. He does not present himself as the Messiah but as the servant of the Messiah who has already come. He does not claim new revelation but preserves and interprets the revelation given once for all to the apostles. The Catholic Church has consistently opposed those who claimed to be Christ or who claimed to have received new revelations that contradicted apostolic teaching. This opposition to false messiahs and false prophets demonstrates that the Church serves Christ rather than opposing him.

Jesus’s promise to be with his Church until the end of the age, recorded in Matthew 28:20, provides an important biblical foundation for understanding the papacy. If Jesus promised to remain with his Church always, then there must be some means by which his authority continues to be exercised in the Church. The Catholic understanding is that this continuing presence and authority operates through the apostolic succession, particularly through Peter’s successor who serves as the visible principle of unity. This understanding allows for a church that continues Christ’s mission authoritatively rather than a church that must constantly reinvent itself or that can fall into complete error. The alternative Protestant view faces the difficulty of explaining how Christ’s presence with the Church is manifested if there is no continuing apostolic authority and if each individual or congregation interprets Scripture independently.

The Acts of the Apostles demonstrates that the early Church had a definite structure of authority and that this authority was exercised to preserve authentic teaching and to resolve disputes. When questions arose about whether Gentiles needed to be circumcised, the apostles and elders met in council to decide the matter, as recorded in Acts 15. Their decision was communicated to the churches with the formula, “It has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us,” indicating that they understood their decision as guided by God and authoritative for believers. This exercise of teaching authority by the apostolic community provides the model for how the Church continues to teach authoritatively today. The pope, in union with the bishops who are successors of the apostles, continues to exercise this teaching authority to preserve the faith and to apply it to new situations and questions that arise.

Paul’s letters reveal his concern for preserving authentic apostolic teaching and his opposition to false teachers who were troubling the early Christian communities. In Galatians 1:8-9, Paul declares that even if an angel from heaven should preach a gospel contrary to what the Galatians had received, that messenger should be accursed. This strong language demonstrates the importance of maintaining the apostolic deposit of faith without addition or subtraction. The Catholic Church’s claim is that the papal office serves precisely this function of preserving apostolic teaching. When the pope defines a doctrine infallibly, he is not adding to revelation but clarifying what has always been believed and taught. This preservative function is the opposite of what the Antichrist does; rather than denying Christ or introducing false teaching, the pope maintains authentic Christian faith against all who would corrupt it.

Conclusion and Practical Application

The claim that the pope is the Antichrist cannot be sustained when Scripture is read carefully and honestly. This accusation arose from the specific historical circumstances of the Protestant Reformation and served polemical purposes rather than reflecting sound biblical interpretation. The biblical term “antichrist” refers specifically to those who deny that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, a definition that clearly does not apply to the papacy. The early Church Fathers, who had a much better understanding of apostolic teaching and biblical context, never identified the bishop of Rome as the Antichrist but rather described this figure as a future political ruler who would claim to be the Messiah himself. The consistent witness of Scripture and Tradition supports understanding the pope as the successor of Peter, charged with shepherding Christ’s flock and preserving apostolic teaching, rather than as the ultimate enemy of Christ.

For Catholics, understanding the true nature of the Antichrist and the proper role of the papacy helps to strengthen faith and to resist genuine manifestations of the antichrist spirit in the world today. This spirit appears in various forms including ideologies that deny objective truth, political systems that claim total authority over human life, and false religious teachings that distort the gospel message. By remaining united with the pope and the bishops in communion with him, Catholics maintain connection with the apostolic faith and resist being swept away by every new teaching or movement that arises. The pope serves as a visible principle of unity and a guardian of orthodoxy, helping believers to remain faithful to Christ even in times of confusion or persecution. This service to the truth is the opposite of what the Antichrist does; it preserves authentic faith rather than promoting deception.

Understanding the biblical foundation for the papacy also helps Catholics to appreciate this gift that Christ has given to his Church. The papal office exists not to dominate believers but to serve them by preserving the faith and maintaining unity. Throughout history, the popes have made mistakes in judgment and some have failed morally, but the office itself continues to serve its essential purpose of maintaining the Church’s unity and orthodoxy. Christ’s promise that the gates of hell would not prevail against his Church has been fulfilled through two millennia of history, despite external persecutions and internal challenges. The papacy has played a crucial role in this preservation of the Church, serving as a reference point for authentic teaching and a rallying point for unity when divisions threatened to tear the Church apart.

For non-Catholics who may have been taught that the pope is the Antichrist, reconsidering this claim in light of biblical evidence and historical context can open new possibilities for understanding the Catholic Church. Many sincere Christians have been led to reject Catholicism based on this false identification without ever examining what the Church actually teaches or what the pope actually claims. A fair hearing requires setting aside prejudice and being willing to consider whether this accusation reflects Scripture’s testimony or merely reflects polemical rhetoric from a particular historical period. The ecumenical movement has helped many Protestants and Catholics to recognize that they share fundamental beliefs about Christ and to work together for the gospel despite remaining differences. Abandoning the inflammatory rhetoric of identifying the pope as the Antichrist represents an important step toward Christian unity and mutual understanding.

The practical application of correctly understanding the Antichrist involves remaining vigilant against real spiritual dangers while not wasting energy fighting imaginary enemies. If Christians identify the wrong target as the Antichrist, they may overlook genuine threats to faith and morals. The spirit of antichrist is present in militant secularism that seeks to remove all reference to God from public life, in moral relativism that denies objective truth, in materialism that reduces human beings to purely physical organisms, and in various ideologies that promise salvation through human effort alone. These movements and ideas genuinely oppose Christ and seek to draw people away from him. By correctly identifying these threats rather than falsely accusing the papacy, Christians can more effectively resist the real work of the enemy and bear witness to the truth of the gospel.

The biblical teaching about the Antichrist should lead believers to deeper faith in Christ rather than to suspicion and division among Christians. John wrote his letters about antichrists not merely to warn about future dangers but to strengthen the faith of believers by clarifying what authentic Christianity entails. Those who confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh and who remain in the apostolic teaching have nothing to fear from the Antichrist, for Christ has already won the victory over all powers of evil through his death and Resurrection. The Church’s mission is to proclaim this victory and to call all people to faith in Christ. The pope serves this mission by maintaining the Church’s fidelity to its Lord and by ensuring that the gospel continues to be preached faithfully in every generation until Christ returns in glory to complete the salvation he began.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.