Brief Overview

- The Catholic Church professes her unity as one of her four essential marks, rooted in the Trinity and established by Christ himself.

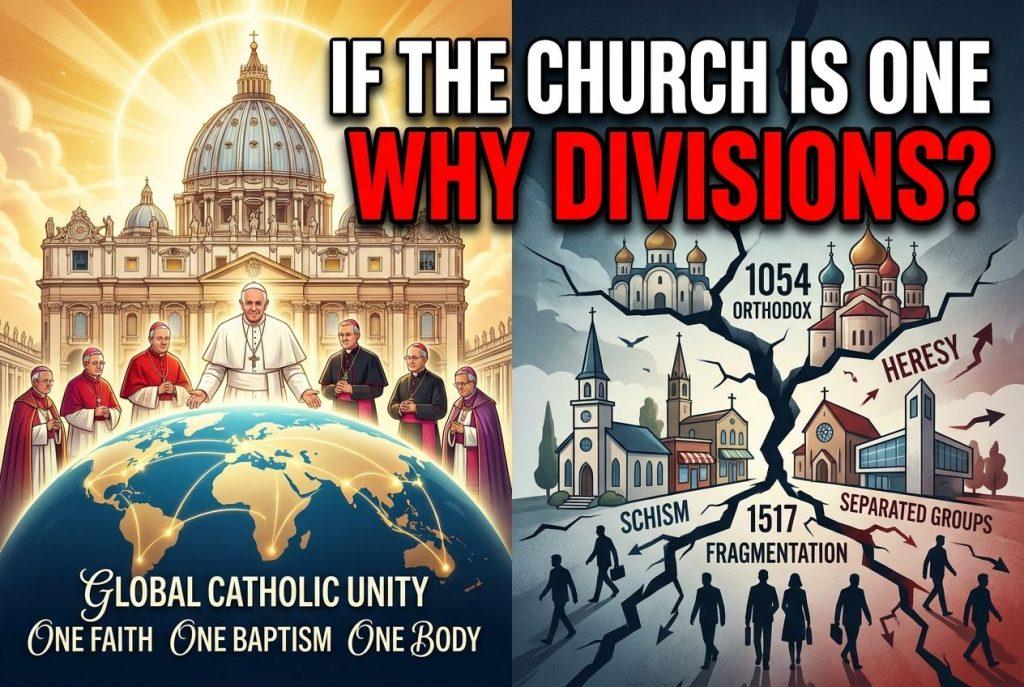

- Divisions among Christians resulted from human sin throughout history, including major separations like the East-West Schism of 1054 and the Protestant Reformation beginning in 1517.

- The Church teaches that visible unity exists fully in the Catholic Church while recognizing that elements of truth and sanctification exist in other Christian communities.

- Christ prayed for the unity of all his followers, making this a divine gift that the Church must constantly work to maintain and restore.

- The Catholic Church actively engages in ecumenism, seeking reconciliation with separated Christians while maintaining the fullness of truth entrusted to her.

- Understanding Church unity requires distinguishing between the Church’s essential oneness and the historical wounds caused by human failure and sin.

The Church’s Essential Unity

The Catholic Church teaches that unity belongs to her very nature and cannot be separated from her identity. This unity finds its source in the Trinity itself, where the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit exist in perfect communion. The Church reflects this divine unity because Christ established her as one body with himself as the head. Every baptized Christian becomes incorporated into this one body, sharing in the life of grace that flows from the sacraments. The Church received her unity as a gift from Christ at the moment of her founding, not as something she created or earned through human effort. This fundamental unity exists independently of human actions or failures. The Second Vatican Council reaffirmed that this unity subsists in the Catholic Church, which means it exists fully and permanently within her visible structure. Catholics believe that Christ willed one Church, not multiple churches, and that this one Church continues throughout history under the guidance of the successors of the apostles. The visible bonds of this unity include professing the same faith received from the apostles, celebrating the same sacraments, and maintaining apostolic succession through the bishops in communion with the Pope. Scripture repeatedly emphasizes this essential unity, as when Saint Paul wrote to the Ephesians about one Lord, one faith, and one baptism.

The unity of the Church goes deeper than mere organization or institutional structure. It represents a spiritual reality that binds all believers together in Christ through the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit acts as the soul of the Church, creating communion among all members and enabling them to share in the divine life. This spiritual unity manifests itself in the sharing of spiritual goods, including faith, sacraments, charisms, and charity. Members of the Church form one body where each part serves the whole and receives nourishment from the same source. The Eucharist stands at the center of this unity, making present the sacrifice of Christ and nourishing believers with his Body and Blood. Through the Eucharist, Christians are not merely united with Christ but also with one another in him. The Church’s unity also encompasses a diversity of gifts, cultures, and traditions that enrich rather than threaten the fundamental oneness. Different particular churches maintain their own legitimate customs and practices while remaining in full communion with the whole Church. This unity in diversity reflects the richness of God’s plan for humanity, where people from every nation and culture come together as one people. The Catholic understanding of unity thus balances the recognition of legitimate diversity with the non-negotiable requirement of communion in faith, sacraments, and hierarchical structure.

Biblical Foundation for Unity

Jesus Christ himself prayed explicitly for the unity of his followers during the Last Supper, as recorded in the Gospel of John. He prayed to the Father that all who would believe in him through the apostles’ word might be one, just as he and the Father are one. This prayer reveals that Christian unity directly reflects the unity of the Trinity and serves as a witness to the world of the Father’s love. Christ intended this unity to be visible and recognizable, not merely a spiritual ideal invisible to human eyes. The unity he prayed for would convince the world that the Father had sent him, making it an essential part of the Church’s mission. Throughout his earthly ministry, Jesus worked to gather the scattered children of God into one flock under one shepherd. He spoke of himself as the good shepherd who lays down his life for the sheep and calls them to follow his voice. The image of one flock under one shepherd emphasizes both the visible and spiritual dimensions of Church unity. Christ established Peter as the rock upon which he would build his Church, giving him the keys of the kingdom and the authority to strengthen his brothers. This appointment of Peter provided a visible foundation for unity that would continue through his successors. Jesus promised that the gates of hell would not prevail against his Church, guaranteeing that the unity he established would endure despite human failures.

The early Christian community understood and lived this unity from the beginning, as shown in the Acts of the Apostles. The first believers devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, fellowship, breaking of bread, and prayers. They held all things in common and distributed goods according to need, manifesting their spiritual unity in practical charity. This visible unity attracted others and led to the rapid growth of the Church despite persecution. Saint Paul addressed threats to unity throughout his letters, treating divisions as serious sins against the body of Christ. Writing to the Corinthians, he strongly condemned their divisions based on following different leaders and called them to be united in mind and judgment. Paul explained that divisions contradict the very nature of Christ, who cannot be divided among competing factions. He emphasized that all Christians, whether Jews or Greeks, slaves or free, were baptized into one body and made to drink of one Spirit. The image of the Church as the body of Christ, with many members but one body, became central to understanding unity. Paul taught that when one member suffers, all suffer together, and when one is honored, all rejoice. This organic unity means that divisions wound not just human relationships but the body of Christ itself. The apostle also stressed that maintaining unity requires humility, gentleness, patience, and bearing with one another in love. He urged believers to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace, recognizing that this unity came from God but required human cooperation to preserve.

Historical Wounds to Unity

The Catholic Church acknowledges that throughout history, serious divisions have damaged the visible unity that Christ willed for his followers. These divisions did not happen suddenly or without cause but developed through complex historical, cultural, theological, and political factors. The Catechism teaches that from the very beginning of the Church, certain rifts arose that the apostles strongly condemned. Even in the New Testament period, false teachers threatened the unity of faith by introducing erroneous doctrines. The early Church faced numerous heresies that denied essential Christian truths about Christ’s nature, the Trinity, or salvation. Church councils worked to maintain unity by defining orthodox teaching and excluding those who rejected core doctrines. However, these early controversies often led to lasting divisions when groups refused reconciliation with the Catholic Church. The theological precision developed through these controversies helped preserve the deposit of faith but sometimes failed to prevent communities from separating. Cultural differences between the Greek-speaking East and Latin-speaking West created tensions that grew over centuries. Different liturgical practices, disciplinary norms, and theological emphases developed in various regions of the Church. While diversity itself does not cause division, it became a source of conflict when combined with mutual misunderstanding and lack of charity. Political factors frequently complicated ecclesiastical disputes, as rulers sought to control churches within their territories.

The Great Schism between East and West, traditionally dated to 1054, resulted from centuries of growing alienation and mutual distrust. Theological disagreements over issues like the procession of the Holy Spirit and the use of leavened or unleavened bread in the Eucharist became symbols of deeper divisions. The question of papal authority proved particularly divisive, with Eastern churches rejecting claims that the Pope possessed immediate jurisdiction over all Christians. Cultural and linguistic barriers made communication difficult and fostered misunderstandings of each other’s positions. The sack of Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204 created lasting bitterness that hardened the division. Political conflicts between Eastern emperors and Western powers reinforced ecclesiastical separation. Both sides bore responsibility for the failure to maintain unity, as the Catechism acknowledges. The Protestant Reformation that began in the sixteenth century created even more extensive divisions within Western Christianity. Martin Luther’s initial concerns about indulgences and other abuses raised legitimate questions about Church practices. However, the controversy quickly expanded to challenge fundamental doctrines about salvation, the sacraments, and Church authority. The invention of the printing press allowed rapid spread of reformers’ ideas and made controlling theological debate much more difficult. Political rulers often supported reformation movements for their own purposes, using religious disputes to assert independence from Rome. The lack of effective reform within the Catholic Church before the Reformation contributed to the crisis’s severity.

The Role of Human Sin

Catholic teaching clearly identifies human sin as the fundamental cause of divisions within Christianity. The Catechism states explicitly that ruptures in Church unity do not occur without human sin on the part of those involved. Where sins exist, divisions, schisms, heresies, and disputes naturally follow as consequences. Conversely, where virtue flourishes, harmony and unity arise from the one heart and soul of believers. Sin damages charity, which binds the Church together in perfect harmony and makes unity visible. When Christians fail to love one another as Christ commanded, the unity he prayed for becomes obscured. Individual sins of hatred, suspicion, judgment, and unwillingness to forgive create division within communities. Collective sins of groups and institutions magnify these effects and can lead to formal separations. Both sides in historical divisions often contributed to the breakdown of unity through their failures in charity and humility. Leaders sometimes pursued power or prestige rather than serving the common good of the Church. Theological disputes escalated into bitter personal conflicts when participants lacked patience and gentleness. Cultural differences became sources of division when Christians failed to see past external customs to their common faith. Political ambitions corrupted ecclesiastical decisions and led to compromises of principle for worldly advantage.

The Catholic Church acknowledges that her own members, including leaders, have sinned in ways that contributed to divisions. Failures in holiness, abuses of authority, and neglect of needed reforms created scandals that pushed some toward separation. The Council of Trent and subsequent Catholic reforms addressed many abuses that had sparked Protestant objections. However, by the time these reforms took effect, the divisions had hardened and reconciliation proved impossible. The Church teaches that while human sin caused the divisions, those born into separated communities cannot be charged with the original sin of separation. Christians raised in Protestant or Orthodox traditions who sincerely follow Christ in their communities have no personal guilt for the historical separations. The Catholic Church accepts them with respect and affection as brothers, recognizing their baptism as valid and their faith as genuine. This distinction between the objective wrongness of division and the subjective innocence of individual Christians proves crucial for ecumenical relations. It allows Catholics to work toward unity without condemning or judging other Christians personally. The focus shifts from assigning blame for past failures to working together toward the unity Christ desires. Understanding sin’s role in creating divisions also suggests the path toward healing them. Conversion of heart, growth in holiness, and increased charity among Christians are essential for restoring unity. Prayer for unity, both individual and communal, asks God’s grace to overcome the human obstacles that maintain separation.

Elements of Truth in Other Communities

The Catholic Church recognizes that many elements of sanctification and truth exist outside her visible boundaries in other Christian communities. These elements include the written Word of God, which Protestant Christians particularly emphasize in their faith and practice. The life of grace operates in baptized Christians of other traditions through the Holy Spirit dwelling within them. Faith, hope, and charity, the theological virtues that unite souls to God, are found among separated Christians who sincerely follow Christ. Interior gifts of the Holy Spirit guide and inspire believers across denominational lines. Various visible elements also exist in other Christian communities, including liturgical practices that honor God and build up faith. Christ’s Spirit uses these churches and ecclesial communities as means of salvation for their members. The power these communities possess to sanctify derives from the fullness of grace and truth that Christ entrusted to the Catholic Church. All genuine blessings in Christian communities come from Christ and lead back to him as their source and goal. These blessings themselves constitute calls to Catholic unity, pointing toward the fullness of means of salvation. The Catholic Church views the existence of truth and grace in other communities not as competition but as signs of hope for reconciliation.

The relationship with Orthodox churches holds special significance because of their particularly close connection to Catholic faith and practice. Orthodox churches maintain apostolic succession through validly ordained bishops in continuity with the apostles. They celebrate valid sacraments, especially the Eucharist, which truly makes present Christ’s Body and Blood. Their theology and spirituality remain largely consistent with Catholic teaching on most fundamental doctrines. The communion between Catholics and Orthodox, though imperfect, lacks little to attain the fullness that would permit shared celebration of the Eucharist. Eastern Catholic churches in full communion with Rome demonstrate that Eastern traditions can flourish within Catholic unity. Protestant communities vary widely in how many elements of Catholic faith and practice they retain. Some maintain episcopal structure, liturgical worship, and high sacramental theology similar to Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Others reject hierarchy, minimize sacraments, and emphasize individual interpretation of Scripture. All validly baptized Christians, regardless of denomination, share real though imperfect communion with the Catholic Church. This existing communion, however incomplete, provides a foundation for ecumenical dialogue and cooperation. Catholics can recognize the genuine faith and devotion of other Christians without denying that full unity requires accepting the whole of Catholic teaching. The Second Vatican Council’s recognition of elements of truth in other communities represented a major development in Catholic ecumenical approach.

The Catholic Church’s Commitment to Ecumenism

The Second Vatican Council declared that restoring unity among all Christians constitutes one of the principal concerns of the Catholic Church. This commitment flows from Christ’s prayer for unity and the Church’s mission to be a sign of unity for all humanity. The Church believes that the unity Christ bestowed on his Church from the beginning subsists in the Catholic Church and can never be lost. However, this does not mean the Church passively accepts the current state of division among Christians. Catholics must always pray and work to maintain, reinforce, and perfect the unity Christ wills for his followers. The desire to recover full unity represents a gift of Christ and a call of the Holy Spirit that the Church must answer. Responding adequately to this call requires several essential elements working together. Permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation drives the ecumenical movement forward. This renewal means Catholics must constantly examine whether they are living up to the Gospel and reforming what falls short. Conversion of heart remains absolutely essential, as the faithful strive to live holier lives according to Gospel teaching. Divisions arose from failures in holiness, so growth in holiness provides the path toward reconciliation. Prayer in common between Catholics and other Christians builds spiritual bonds even before visible unity is achieved. Public and private prayer for Christian unity deserves the name spiritual ecumenism and forms the soul of the movement.

Fraternal knowledge of one another breaks down stereotypes and misunderstandings that perpetuate division. When Christians of different traditions actually meet and interact, they often discover more common ground than expected. Ecumenical formation helps Catholics and others understand both the legitimate diversity within Christianity and the genuine obstacles to full communion. Dialogue among theologians addresses doctrinal differences in a spirit of truth and charity. These scholarly conversations can identify where apparent disagreements rest on linguistic or cultural misunderstandings. They can also clarify where real doctrinal differences exist that require further work to resolve. Meetings among Christians of different churches and communities at all levels build relationships that support formal dialogues. Collaboration among Christians in service to humanity demonstrates the unity they already share in Christ. Working together for justice, peace, and human dignity shows the world that Christians can act as one despite remaining divisions. However, cooperation in good works cannot substitute for the theological work needed to achieve full doctrinal unity. The Catholic Church engages in ecumenism with hope but also with realism about the challenges involved. Some differences between Catholic teaching and Protestant positions involve fundamental questions about revelation, salvation, and Church structure. Resolving these disagreements requires not just good will but also the grace of the Holy Spirit working in hearts and minds. The Church places ultimate hope for Christian unity not in human effort alone but in Christ’s prayer and the Holy Spirit’s power.

Understanding Heresy, Apostasy, and Schism

The Catholic Church distinguishes among different types of separation from full communion, recognizing that they involve varying degrees of rejection of Catholic teaching and practice. Heresy occurs when a baptized Christian obstinately denies or doubts a truth that must be believed with divine and Catholic faith. This involves rejecting defined dogmas that the Church teaches as revealed by God and necessary for salvation. A heretic picks and chooses among Catholic doctrines, accepting some while rejecting others based on personal judgment. The word heresy comes from a Greek term meaning choice, reflecting this selective approach to revealed truth. Examples of heresies include denying the divinity of Christ, rejecting the Trinity, or claiming that faith alone without works leads to salvation. Heresy differs from mere error or ignorance because it involves willful rejection of known Church teaching. Someone who never learned Catholic doctrine or misunderstands it through no fault of their own does not commit heresy. Apostasy represents an even more complete break, being the total repudiation of the Christian faith by a baptized person. An apostate does not merely reject certain doctrines but abandons Christianity altogether. This might involve joining a non-Christian religion or adopting atheism after previously practicing Christian faith. Apostasy breaks all bonds of communion with the Church and represents the most serious form of separation.

Schism specifically refers to refusal of submission to the Pope or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him. A schismatic might accept all or most Catholic doctrines but rejects the Pope’s authority or breaks communion with other Catholics. The Greek word schism means split or tear, indicating a breaking of the visible bonds of Church unity. Schism wounds the body of Christ by dividing what should remain united under one head. The East-West division of 1054 represents a classic case of schism, as the primary issue was papal authority rather than fundamental doctrine. Some Protestant groups began as schism but developed heretical teachings over time as they departed from Catholic doctrine. Other Protestant communities started with heretical teaching that then led to schism from Rome. In practice, these categories often overlap in complex ways that make precise classification difficult. The Catholic Church uses these distinctions primarily for canonical and theological purposes, not to condemn individuals. Most Christians today were born into their religious communities and cannot be held personally responsible for historical separations. The Church recognizes that sincere Protestants and Orthodox who follow Christ within their traditions are not guilty of heresy, apostasy, or schism. These terms apply to the objective situation of separation, not to subjective guilt of individuals. Understanding these distinctions helps clarify what unity requires and what obstacles must be overcome. Full unity means not just mutual recognition or cooperation but also resolving doctrinal differences and restoring communion in faith and structure.

Unity and the Marks of the Church

Catholics profess in the Nicene Creed that the Church is one, holy, catholic, and apostolic, identifying her essential characteristics. These four marks or attributes necessarily belong to the Church because Christ makes her what she is. The Church does not possess these qualities of herself but receives them as gifts from Christ through the Holy Spirit. Unity stands first among the marks, indicating its fundamental importance to the Church’s identity. The Church’s unity reflects the unity of the Trinity, from which all creation and redemption flow. Understanding the Church as one requires seeing how this mark relates to her holiness, catholicity, and apostolicity. The Church is holy not because all her members are sinless but because Christ sanctifies her and gives her the means of holiness. Even while including sinners, the Church remains the holy people of God called to grow in sanctification. Apparent contradictions between the Church’s holiness and the sins of her members puzzle many observers. However, Catholic teaching distinguishes between the Church as Christ’s bride and body, which is holy, and individual members who struggle with sin. The Church is catholic, meaning universal, because Christ is present in her and sends her to all humanity. Her catholicity means she possesses the fullness of means of salvation and extends her mission to every people and culture.

The Church is apostolic because she is built on the foundation of the apostles and continues their mission and teaching. Apostolicity ensures continuity between the Church today and the Church Christ founded on Peter and the apostles. The bishops, as successors of the apostles, maintain this connection through apostolic succession. These four marks together constitute visible signs that point to the Church’s divine origin and mission. They provide criteria for identifying where the Church established by Christ continues to exist. Protestant communities claim to embody these marks in various ways, particularly emphasizing holiness and apostolicity of doctrine. Catholics respond that while elements of these marks exist outside the Catholic Church, their fullness subsists within her. The unity mark proves particularly significant for evaluating competing claims about which church is Christ’s true Church. A church divided into thousands of denominations with contradictory teachings lacks the visible unity Christ intended. Catholics argue that true unity requires not just spiritual connection but also visible bonds of faith, sacraments, and hierarchical communion. The fact that the Catholic Church maintains these visible bonds worldwide provides evidence of her unique claim to be the one Church of Christ. However, Catholics acknowledge that living up to these marks remains an ongoing challenge requiring constant renewal and reform.

The Church’s Mission for Unity in the Modern World

The Catholic Church continues to actively work toward Christian unity while maintaining her claim to possess the fullness of means of salvation. This involves a delicate balance between dialogue with other Christians and fidelity to Catholic teaching. The Church cannot compromise defined dogmas or abandon essential elements of faith in the name of unity. True unity must be unity in truth, not merely agreement to disagree about fundamental matters. At the same time, the Church recognizes that rigidity and lack of charity have contributed to maintaining divisions. Catholics must approach ecumenical dialogue with both confidence in their faith and humility about their own failures. The Church’s ecumenical efforts focus on different approaches depending on the particular Christian community involved. Dialogue with Orthodox churches addresses relatively narrow issues like papal authority and the filioque clause. Catholic and Orthodox churches share so much in common that full reconciliation seems genuinely possible. Conversations with Protestant communities require addressing more fundamental questions about Scripture, tradition, and Church authority. Some Protestant groups have moved closer to Catholic positions through ecumenical dialogue, while others have diverged further. The Church continues these efforts despite limited visible results because Christ’s prayer for unity demands persistent work.

Contemporary challenges to Christian unity include not just historical divisions but also new disagreements over moral teaching. Protestant churches increasingly divide over issues like marriage, human sexuality, and the sanctity of life. Some Protestant communities have adopted positions on these matters that contradict traditional Christian teaching. These developments complicate ecumenical relations and raise questions about what unity would mean in practice. The Catholic Church maintains that unity cannot ignore or minimize disagreements about fundamental moral truths. At the same time, Catholics find allies among orthodox Protestants who uphold traditional Christian sexual ethics and family values. This creates opportunities for cooperation in defending religious freedom and promoting human dignity. The Church’s ecumenical vision extends beyond Christianity to include respectful relations with Jews, Muslims, and others. While seeking full communion with other Christians, the Church also builds bridges with non-Christian religions. This broader dialogue recognizes that all humanity shares a common origin and destiny in God. However, the Church distinguishes between ecumenism among Christians and interreligious dialogue with non-Christians. Ecumenism properly refers only to seeking unity among those who confess Christ as Lord and Savior. The Church’s commitment to unity reflects her mission to be a sacrament of unity for all humanity, gathering scattered peoples into one family. Divisions among Christians undermine this mission by presenting a fractured witness to the world. When Christians compete and contradict one another, they make it harder for others to believe in Christ and his Church.

Practical Implications for Catholic Life

Individual Catholics share responsibility for promoting Christian unity through their personal attitudes, prayers, and actions. This begins with understanding and embracing the Church’s teaching about unity and ecumenism. Catholics should reject both indifferentism that treats all churches as equally valid and triumphalism that dismisses other Christians with contempt. Instead, they should hold together confidence in Catholic truth with respect and charity toward other Christians. Prayer for Christian unity should be a regular part of Catholic spiritual life, not just during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. Catholics can pray that the Holy Spirit will guide all Christians into full truth and communion. They should also pray for their own conversion and growth in holiness, recognizing that Catholic failures contribute to ongoing division. Personal relationships with Christians of other traditions provide opportunities to demonstrate Catholic faith and practice. These relationships should be characterized by honesty about differences combined with genuine friendship and mutual respect. Catholics should neither hide their beliefs nor aggressively argue about them in inappropriate contexts. When questions arise naturally in conversation, Catholics can explain Church teaching charitably and invite further dialogue. Participating in appropriate ecumenical events and services can build understanding while respecting boundaries. Catholics may join other Christians for prayer, Scripture study, and works of charity. However, they should not participate in activities that imply acceptance of Protestant theology or rejection of Catholic distinctives.

The question of receiving Communion in other churches or allowing non-Catholics to receive Catholic Communion requires careful attention to Church law and theology. Generally, Catholics should not receive Communion in Protestant services because these churches lack valid orders and do not share Catholic Eucharistic faith. Receiving Orthodox sacraments may be permitted in certain circumstances because Orthodox orders and sacraments are valid. Non-Catholic Christians generally may not receive Catholic Communion because doing so implies communion of faith that does not yet exist. Exceptions exist for Orthodox Christians and others in grave necessity who freely request the sacrament and demonstrate proper faith. These restrictions do not reflect lack of charity but rather honor the profound meaning of Eucharistic communion. Catholics should explain these policies to non-Catholic friends and family members in a way that communicates respect for their faith while maintaining Catholic principles. Working together with other Christians on shared social concerns demonstrates the unity that already exists and builds relationships. Catholics can collaborate with Protestants, Orthodox, and others in defending human life, serving the poor, and promoting justice. This cooperation shows that Christians can work as one even while doctrinal differences remain. It also provides a foretaste of the full communion Catholics hope to achieve eventually. Catholics should support and participate in formal ecumenical dialogues at local, national, and international levels. Bishops and theologians carry primary responsibility for these dialogues, but ordinary Catholics can encourage and pray for their success.

The Hope for Full Unity

The Catholic Church maintains hope that full visible unity among all Christians will eventually be restored, though she cannot predict when or how this will occur. This hope rests on trust in Christ’s promise that the Holy Spirit will guide the Church into all truth. It also flows from Christ’s prayer for unity, which must be effective because the Father always hears the Son. Catholics believe that unity is ultimately a gift from God, not an achievement of human diplomacy or compromise. Therefore, they continue working toward unity while acknowledging that only God can bring it to completion. The Church envisions restored unity not as absorption of other Christians into current Catholic structures but as reconciliation into full communion. This might involve Orthodox churches and some Protestant communities maintaining distinctive traditions and practices within Catholic unity. The Eastern Catholic churches provide a model of how different liturgical and theological traditions can exist in full communion with Rome. These churches retain Eastern practices while accepting papal authority and Catholic dogma. Similar arrangements might allow reconciled Protestant communities to preserve some of their distinctive emphases and customs. However, full unity necessarily requires accepting essential Catholic teachings about the Pope, the seven sacraments, and other defined dogmas. Catholics cannot compromise on matters of divine revelation in the name of unity. The Church teaches that Christ willed one Church with specific characteristics, not a federation of churches with contradictory beliefs.

Some Catholics express frustration with the slow pace of ecumenical progress and wonder whether full unity is realistic. The Second Vatican Council’s optimism about rapid reconciliation has not been fulfilled in the decades since. Some ecumenical dialogues seem to have reached impasses on fundamental issues with little prospect of resolution. However, the Church’s commitment to ecumenism does not depend on seeing immediate results or guaranteed success. Christians must pursue unity because Christ commanded it, regardless of whether human wisdom sees how it can be achieved. Unexpected developments throughout Church history show that God can open doors that seemed permanently closed. The fall of communism, which had divided Christians in Eastern Europe, came suddenly when few predicted it. Changes in Protestant attitudes toward Catholicism show that positions once thought fixed can evolve over time. Each generation of Christians must do what it can to promote unity and leave the results to God. Even if full visible unity is not achieved in our lifetime, the work of understanding, dialogue, and cooperation remains valuable. It reduces hostility, corrects misunderstandings, and builds relationships that witness to Christ’s love. Catholics should maintain realism about the difficulties without falling into cynicism or despair. The unity Christ prayed for will ultimately be achieved because his prayer cannot fail. Christians can trust that what God has begun, he will bring to completion in his time and way.

Living as One Church Despite Divisions

The Catholic Church teaches that she remains one Church despite the existence of divisions among Christians. The unity Christ gave to his Church subsists in the Catholic Church and cannot be destroyed by human sin. Catholics are already in the one Church and share bonds of communion with all validly baptized Christians. This does not mean Catholics can be complacent about division or cease working toward full visible unity. Rather, it means they can live and act as members of the one Church while acknowledging the reality of separation. The Church’s essential unity shows itself in the communion of Catholics worldwide who share one faith, one baptism, and one table. This visible unity across cultures, languages, and continents demonstrates what Christ intended for all his followers. Catholics should appreciate and strengthen the bonds of unity within the Church while working to extend them to separated Christians. Parish communities model unity by welcoming members from different backgrounds and helping them grow together in faith. The celebration of the Eucharist makes present the unity of the Church, as many grains of wheat become one bread and many grapes become one cup. Catholics are literally united to one another through communion in the Body and Blood of Christ. Families divided by different Christian affiliations face particular challenges in living out Church unity. Catholic family members should maintain both fidelity to their faith and loving respect for Protestant or Orthodox relatives.

These situations require wisdom to balance honoring religious differences with maintaining family harmony. Major life events like weddings and funerals often bring these tensions to the surface and require sensitivity. Catholics should not judge or condemn family members who belong to other Christian traditions. At the same time, they should not compromise their own faith or avoid sharing it when appropriate. Prayer for family members’ conversion may be appropriate but should not replace treating them with genuine love and respect. Mixed marriages between Catholics and other Christians require special attention to maintain both Church unity and marital unity. These couples should discuss religious differences honestly before marriage and reach clear agreements about raising children. The Church encourages the non-Catholic partner to respect the Catholic partner’s obligations and supports raising children as Catholics. However, the Church also recognizes that mixed marriages can promote ecumenical understanding when couples approach their differences with maturity. Catholic education at all levels should include teaching about Church unity, ecumenism, and respectful relations with other Christians. Children and young people should learn both what makes the Catholic Church unique and what Catholics share with other Christians. They need formation that equips them to explain their faith charitably and dialogue with non-Catholic peers. Catholic institutions can provide opportunities for ecumenical learning and cooperation while maintaining clear Catholic identity. The goal is forming Catholics who are both confident in their faith and genuinely open to others.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.