Brief Overview

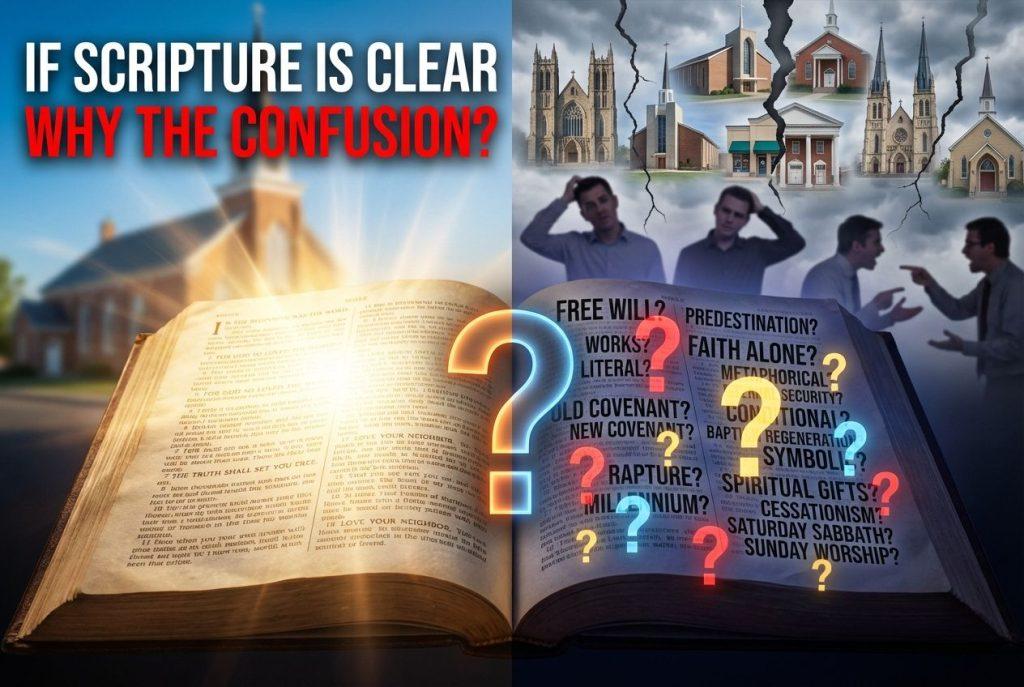

- Scripture contains divine truth that God intends for humanity to understand, yet the reality of widespread disagreement about its meaning challenges the notion of complete clarity.

- Human nature has been weakened by original sin, which affects our ability to comprehend spiritual truths without assistance from the Church and the Holy Spirit.

- The Bible was written in ancient languages and cultural contexts that require careful study and interpretation to avoid misunderstanding the sacred authors’ intentions.

- Catholic teaching holds that Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium work together as interconnected sources of divine revelation that cannot be separated.

- Many passages of Scripture admit multiple valid interpretations within the bounds of orthodoxy, while the Church has definitively interpreted relatively few specific verses.

- The existence of thousands of Protestant denominations with conflicting interpretations demonstrates the practical consequences of rejecting authoritative teaching authority in favor of private judgment.

The Nature of Biblical Clarity

The Catholic Church teaches that Sacred Scripture is indeed clear in communicating what is necessary for salvation. God speaks to humanity through the biblical text, and His message can be understood by those who approach it with faith and humility. However, this clarity does not mean that every passage is equally transparent or that readers will automatically grasp the full meaning without assistance. The Church recognizes a distinction between the essential truths of the faith, which are accessible to all believers, and the deeper theological meanings that require more extensive study and guidance. Scripture itself acknowledges its own complexity, as Peter notes in his second letter when he describes Paul’s writings as containing “some things hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction” in 2 Peter 3:16. This biblical admission that certain passages present interpretive challenges stands as a counter to claims that all of Scripture is self-evident. The very fact that Peter warns against misinterpretation indicates that understanding requires more than simply reading the words on the page.

The Catechism teaches that “in Sacred Scripture, God speaks to man in a human way” and that correct interpretation requires attentiveness to what the human authors truly wanted to affirm and what God wanted to reveal through their words (CCC 109). This dual authorship of Scripture means that readers must engage both with the literal sense intended by the human writer and the spiritual sense intended by the Divine Author. The literal sense involves understanding the historical, cultural, and linguistic context in which the text was produced. The spiritual sense encompasses the deeper meanings that point toward Christ, moral instruction, and eternal realities. These multiple layers of meaning demonstrate that biblical clarity operates at different levels, and full comprehension requires careful study guided by the Holy Spirit and the teaching authority of the Church. The Church has always maintained that while Scripture is sufficient for salvation, it is not always simple or straightforward in every detail.

The Effects of Original Sin on Human Understanding

Original sin has left permanent marks on human nature that directly impact our ability to understand spiritual truths. When Adam and Eve fell from grace, they did not lose their fundamental human faculties, but these faculties became weakened and disordered. The Catechism teaches that “as a result of original sin, human nature is weakened in its powers, subject to ignorance, suffering and the domination of death, and inclined to sin” (CCC 418). This inherited condition affects every person born into the world and has direct consequences for biblical interpretation. Our intellects have been darkened, which means our natural capacity to perceive truth has been diminished. Our wills have been weakened, making it more difficult to submit to truths that challenge our preferences or preconceptions. Our emotions and desires have become disordered, causing us to be attracted to interpretations that satisfy our fallen inclinations rather than conforming to divine revelation.

The darkening of the intellect means that human reason, while still functional and valuable, cannot reliably arrive at all spiritual truths without divine assistance. We see through a glass darkly, as Paul describes in 1 Corinthians 13:12, and our fallen condition predisposes us toward error. This is not to say that human beings are completely incapable of understanding anything, which would be an exaggeration. Rather, it acknowledges the real limitations that sin has imposed on our cognitive abilities when it comes to grasping divine mysteries. The weakening of the will compounds this problem because even when we do perceive the truth, we may lack the moral strength to accept it if it conflicts with our desires or requires difficult changes in belief or behavior. People often reject correct interpretations of Scripture not because the meaning is unclear but because accepting that meaning would require acknowledging sin, changing deeply held opinions, or accepting authority they resist.

The disorder in human passions creates another obstacle to correct interpretation. We are inclined toward pride, which makes us resistant to correction and overly confident in our own understanding. We are drawn toward what pleases us rather than what is true. We are influenced by our social environment, our upbringing, and our personal experiences in ways that can cloud our judgment. These factors operate below the level of conscious awareness, shaping how we approach the biblical text before we even begin reading. Catholic teaching recognizes these human weaknesses and provides remedies through grace, the sacraments, and the authoritative guidance of the Church. The Holy Spirit works through these means to heal our intellects, strengthen our wills, and order our desires toward truth. Without this supernatural assistance, the effects of original sin would leave us helplessly confused about even basic spiritual realities. The persistence of interpretive confusion in communities that reject Church authority demonstrates the practical effects of this fallen condition.

The Role of Language and Cultural Context

Scripture was written over the course of approximately 1,500 years by numerous authors in three ancient languages that differ significantly from modern tongues. The Old Testament was composed primarily in Hebrew, with some portions in Aramaic, while the New Testament was written in Greek. Each of these languages has unique grammatical structures, vocabulary ranges, and conceptual frameworks that do not translate perfectly into contemporary languages. Hebrew, for instance, is a concrete language that often uses physical imagery to express abstract concepts. Greek possesses philosophical precision and multiple words for concepts that English expresses with single terms. Aramaic bridges Semitic and other Near Eastern linguistic traditions. When Scripture is translated into modern languages, something is inevitably lost or transformed in the process. Translators must make countless decisions about which English word best captures the original meaning, and reasonable scholars can disagree about these choices. The result is that readers of English Bibles are already at least one step removed from the original text, viewing it through the lens of translation decisions made by others.

The cultural context in which Scripture was written presents similar challenges. The biblical world was radically different from our own in its social structures, economic systems, political arrangements, and daily practices. References that would have been immediately clear to original audiences often require extensive explanation for modern readers. When Jesus speaks of shepherds, vineyards, or fishing, He draws on concrete realities familiar to His listeners but foreign to contemporary urban dwellers. When Paul discusses social relationships between masters and slaves, husbands and wives, or Jews and Gentiles, he operates within a cultural framework that no longer exists in the same form. Understanding these passages requires knowledge of ancient social customs, legal systems, and cultural assumptions. Without this background knowledge, readers can easily misunderstand the text or apply it in ways the original author never intended.

The literary forms and conventions of ancient writing add another layer of complexity. Scripture contains multiple genres including historical narrative, poetry, wisdom literature, prophecy, apocalyptic writing, parables, and epistles. Each genre follows different rules and must be interpreted according to its own conventions. Taking poetry literally or treating parables as straightforward historical accounts leads to confusion and error. The Catechism emphasizes that readers must “take into account the conditions of their time and culture, the literary genres in use at that time, and the modes of feeling, speaking and narrating then current” (CCC 110). This requires specialized knowledge that ordinary readers often lack. Historical and archaeological research continues to shed new light on biblical passages by revealing details about ancient life, customs, and languages. What seemed obscure to previous generations sometimes becomes clearer as scholars deepen their understanding of the biblical world. This ongoing process of discovery demonstrates that biblical interpretation is not a simple matter of reading the text with no assistance, but rather requires engagement with the accumulated wisdom of scholarship and tradition.

Scripture, Tradition, and the Magisterium

Catholic teaching presents a three-fold foundation for understanding divine revelation that distinguishes its approach from Protestant models. Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium form an interconnected whole that cannot be properly separated. The Catechism states that these three “are so connected and associated that one of them cannot stand without the others” and that “working together, each in its own way, under the action of the one Holy Spirit, they all contribute effectively to the salvation of souls” (CCC 95). This integrated approach recognizes that the written text of Scripture emerged from the living faith of the Church and must be understood within that same living tradition. The apostles preached the Gospel before it was written down, and the early Christian communities existed and flourished before the New Testament was compiled. The written text represents a portion of the apostolic teaching, but not its entirety. Oral tradition preserved and transmitted teachings that complemented the written word.

The Magisterium serves as the authentic interpreter of both Scripture and Tradition. The task of giving an authoritative interpretation of the Word of God has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the Pope (CCC 85). This teaching authority is not positioned above Scripture but rather serves as its guardian and authentic interpreter. The Magisterium “teaches only what has been handed on to it” and listens devotedly to divine revelation, guards it with dedication, and expounds it faithfully (CCC 86). The bishops do not create new doctrine but rather preserve, explain, and apply the deposit of faith that was entrusted to the Church by Christ and the apostles. This authoritative teaching office provides the necessary guidance to resolve interpretive disputes and maintain doctrinal unity. Without it, Christians inevitably fragment into competing interpretations with no objective means of resolving their differences.

The relationship between these three elements can be understood through the analogy of a family. Scripture is like the written family history and instructions left by the parents. Tradition is like the living memory and ongoing life of the family, the practices and beliefs passed down from generation to generation. The Magisterium is like the parental authority that interprets the family rules, applies them to new situations, and settles disputes among the children. Just as children benefit from parental guidance in understanding family traditions and written instructions, so believers benefit from the Magisterium’s guidance in understanding Scripture and Tradition. This does not mean that individual believers cannot read and study Scripture for themselves. The Church encourages personal Bible study and meditation on God’s Word. However, it recognizes that individual interpretation must ultimately be tested against the Church’s teaching to ensure orthodoxy. The sensus fidei, or sense of the faith, possessed by all believers when properly formed, aligns with the authoritative teaching of the Church rather than contradicting it.

The Four Senses of Scripture

Catholic tradition has long recognized that Scripture can be understood on multiple levels simultaneously. The Catechism distinguishes between the literal sense and the spiritual sense, with the spiritual sense further divided into three subcategories. This framework provides a sophisticated approach to interpretation that honors both the historical meaning of the text and its deeper theological significance. The literal sense “is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation” (CCC 116). This involves careful attention to what the human author intended to communicate through his words. The literal sense is not simplistic or superficial but rather requires scholarly study of language, context, and literary form. All other senses of Scripture are based on the literal sense, which serves as the foundation for deeper interpretation.

The spiritual senses open up additional layers of meaning that God has embedded in the text beyond what the human author may have consciously intended. The allegorical sense recognizes the typological connections between Old and New Testament events, seeing how earlier realities point forward to Christ. For example, the crossing of the Red Sea in Exodus can be understood as a type or prefigurement of Christian baptism, both involving passage through water to liberation and new life. The moral sense draws practical lessons for Christian living from the events and teachings of Scripture. The stories and commands in the Bible instruct believers on how to act justly and grow in virtue. The anagogical sense points toward eternal realities and the heavenly fulfillment of God’s plan. Earthly realities described in Scripture become signs of heavenly truths, such as the Church militant on earth pointing toward the Church triumphant in heaven.

This multi-layered approach to interpretation explains how passages can have multiple valid meanings without contradiction. A historical event really happened as described in the literal sense, but that same event also carries deeper significance as a type of Christ, a moral lesson, and a sign of heavenly realities. Medieval scholars summarized this framework in a couplet: “The Letter speaks of deeds; Allegory to faith; The Moral how to act; Anagogy our destiny” (CCC 118). This interpretive method guards against both shallow literalism that misses the depth of Scripture and allegorical excess that ignores the historical foundation. It recognizes that God’s Word is inexhaustibly rich and can be meditated on at progressively deeper levels. A passage that seems simple on first reading reveals new dimensions when examined through these different lenses. The Church has employed this method throughout her history to draw out the full meaning of Scripture while maintaining fidelity to the text.

The Limits of Private Interpretation

The Protestant Reformation introduced a principle that has had enormous consequences for Christian unity and biblical interpretation. The idea that individual believers can interpret Scripture for themselves without reference to Church authority, sometimes called the doctrine of private judgment, was a radical departure from Christian tradition. While the Reformers did not initially intend for this principle to lead to endless division, the historical record demonstrates its practical effects. From the original split between Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin, Protestantism has continually fractured into smaller and smaller groups disagreeing about fundamental doctrines. Today there are thousands of Protestant denominations, each claiming to base its beliefs on Scripture alone, yet reaching contradictory conclusions about essential matters of faith. Some practice infant baptism while others reject it. Some believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist while others view it as purely symbolic. Some maintain hierarchical church government while others embrace congregationalism. These disagreements are not minor or peripheral but touch the core of Christian belief and practice.

The New Testament itself warns against relying solely on personal interpretation. Peter writes that “no prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation” in 2 Peter 1:20. While this verse primarily addresses how Scripture was produced rather than how it should be read, the principle applies to both. The prophets did not speak from their own understanding but from divine inspiration, and similarly, readers should not interpret according to their own private judgment apart from the Church’s guidance. The account of Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8:26-40 provides a practical illustration of the need for authoritative teaching. The eunuch was reading Isaiah but could not understand it without help. When Philip asked if he understood what he was reading, the eunuch replied, “How can I, unless someone guides me?” Philip then explained the passage to him, showing how it pointed to Jesus. This episode demonstrates that even sincere seekers reading Scripture need authoritative guidance to grasp its full meaning.

The Catholic approach does not forbid personal Bible reading or study. On the contrary, the Church encourages believers to immerse themselves in Scripture and meditate on God’s Word daily. However, personal reading must be done within the context of the Church’s teaching and tradition. Individual insights and applications are valuable but must be tested against the authoritative interpretation of the Magisterium. This balance preserves both personal engagement with Scripture and protection against error. When individuals rely solely on their own understanding, they inevitably read Scripture through the lens of their own preconceptions, biases, and cultural assumptions. They lack the broader perspective that comes from the accumulated wisdom of two thousand years of Christian reflection on these texts. They have no objective standard by which to judge whether their interpretation is correct or erroneous. The result is the chaos of competing interpretations that characterizes much of contemporary Protestantism, where each person becomes his own pope and Scripture means whatever the individual thinks it means.

The Complexity of Biblical Themes

Certain biblical themes and doctrines are genuinely complex and admit different levels of understanding. The relationship between divine sovereignty and human free will, for instance, has been debated by Christian theologians for centuries. Scripture affirms both that God is sovereign over all things and that human beings make real choices for which they bear moral responsibility. Harmonizing these truths requires careful theological reflection and acceptance of mystery. Different Catholic theologians have proposed various models for understanding how God’s grace and human freedom interact, and the Church allows legitimate theological diversity on this question within the bounds of orthodoxy. Similarly, the doctrine of the Trinity requires accepting that God is one being existing as three persons, a reality that transcends human categories and cannot be fully comprehended by finite minds. Scripture reveals this truth gradually through both testaments, and it took several centuries of theological development for the Church to formulate precise Trinitarian language.

The relationship between faith and works provides another example of biblical complexity. James writes that “faith without works is dead” in James 2:26, while Paul repeatedly emphasizes that salvation comes through faith apart from works of the law. Protestant interpreters have sometimes seen these as contradictory, leading to debates about whether James should even be included in the biblical canon. Catholic theology recognizes no contradiction because it understands that Paul addresses works of the Mosaic law while James addresses the works of charity that flow from living faith. Saving faith necessarily produces good works as its fruit, but those works do not earn salvation in the sense of placing God in our debt. Both emphases are necessary to capture the full biblical picture. Scripture presents these truths in dynamic tension rather than as a neat systematic theology, and believers must hold both poles without collapsing one into the other.

Eschatological passages present particular interpretive challenges because they use apocalyptic imagery that is highly symbolic and often deliberately obscure. The Book of Revelation has spawned countless interpretations throughout Church history, and the Church has definitively interpreted very few of its passages. Similarly, Jesus’s teachings about the end times in the Gospels combine warnings about the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD with prophecies about the final judgment, and distinguishing between these two events requires careful study. The Church teaches that Christ will return visibly at the end of history to judge the living and the dead, but she has not endorsed any particular timeline or detailed scenario for how events will unfold. Believers should focus on being spiritually prepared for Christ’s return rather than attempting to construct elaborate end-times charts. The existence of many competing eschatological schemes among Protestants demonstrates how easily people can go astray when they lack authoritative guidance in interpreting difficult passages.

The Historical Development of Doctrine

Understanding Scripture correctly requires recognizing that Christian doctrine has developed over time as the Church has reflected more deeply on the deposit of faith. This does not mean that the Church creates new doctrines that contradict earlier teaching, but rather that she comes to understand more fully and express more precisely what was implicit in divine revelation from the beginning. The doctrine of the Trinity provides a clear example. The New Testament contains the raw data for Trinitarian theology in passages like Matthew 28:19, where Jesus commands baptism in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and 2 Corinthians 13:14, which speaks of the grace of Christ, the love of God, and the fellowship of the Spirit. However, the precise formulation that God is one substance in three persons required several centuries of theological debate and conciliar decisions. Heresies like Arianism and Sabellianism pushed the Church to develop more exact language to express biblical truth against error.

The canon of Scripture itself represents a development requiring authoritative decision. The early Church possessed various writings that were read in Christian worship, but it took time to discern which books were truly inspired and apostolic. The Church evaluated these texts according to criteria including apostolic authorship or authorization, conformity to the rule of faith, and universal acceptance among Christian communities. The final shape of the biblical canon was not formally settled until the late fourth century, and even then, questions persisted about certain books. The Protestant Reformers removed seven books from the Old Testament that had been accepted by the Church for over a thousand years, creating a shorter canon than the one used by Catholics and Orthodox. This demonstrates that determining which books belong in Scripture is not a matter of self-evident clarity but requires authoritative judgment by the Church.

Christological definitions provide another example of doctrinal development. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD defined that Christ possesses two complete natures, divine and human, united in one person. This precise formulation resolved debates about how to understand the biblical testimony that Jesus is both fully God and fully man. Earlier heresies had either divided Christ into two persons or merged His natures into one mixed nature. The Chalcedonian definition guards the biblical truth against both extremes, affirming that Christ is “one person in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” This language goes beyond what Scripture states explicitly but faithfully expresses what Scripture implies and what the Church has always believed. The development of doctrine demonstrates that reading Scripture fruitfully requires engagement with the Church’s living tradition and authoritative teaching across the centuries.

The Role of the Holy Spirit

Catholic teaching emphasizes that the same Holy Spirit who inspired the writing of Scripture must also guide its interpretation. The Catechism states that “Sacred Scripture must be read and interpreted in the light of the same Spirit by whom it was written” (CCC 111). This principle recognizes that biblical interpretation is not merely an intellectual exercise but a spiritual activity requiring divine assistance. The Holy Spirit works through multiple channels to guide believers into truth. He illuminates the minds of individual readers, helping them grasp the meaning of the text and apply it to their lives. He speaks through the collective wisdom of the Church, guiding the development of doctrine and the discernment of truth. He protects the Magisterium from error when it teaches definitively on matters of faith and morals. These different modes of the Spirit’s action work together harmoniously rather than conflicting with each other.

The promise of the Holy Spirit guiding the Church into all truth, recorded in John 16:13, provides the foundation for confidence in the Church’s teaching authority. Jesus promised that the Spirit would lead His disciples into complete truth and would bring to their remembrance everything He had taught them. This promise was given not only to the original apostles but to their successors throughout Church history. The Spirit’s guidance explains how the Church can maintain doctrinal unity and continuity across two thousand years despite cultural changes, persecution, internal controversies, and the failings of individual members. Without the Spirit’s protection, the Church would have fragmented immediately or drifted into error long ago. The survival and growth of the Church testifies to the Spirit’s faithful guidance.

Personal illumination by the Holy Spirit is real and valuable, but it must be distinguished from private inspiration that contradicts Church teaching. Individuals do receive insights and applications from Scripture that the Spirit uses to guide their lives and deepen their faith. However, when someone believes the Spirit has revealed an interpretation that conflicts with the Church’s teaching, one of these claims must be incorrect. Catholic theology recognizes that individual believers can be mistaken about what they think the Spirit is telling them, either through self-deception, disordered desires, or the influence of evil spirits disguised as angels of light. The Church provides the objective standard by which to test spiritual experiences and interpretations. The genuine work of the Holy Spirit in individual hearts will always align with the Spirit’s guidance of the Church as a whole.

Practical Consequences of Interpretive Disagreement

The existence of widespread confusion about Scripture’s meaning has real consequences for Christian life and witness. When Christians disagree about fundamental doctrines, it undermines the credibility of Christianity in the eyes of non-believers. If Jesus established a church and left clear teaching, why do His followers disagree so profoundly about what that teaching means? This question troubles many sincere seekers who observe Christian disunity. The scandal of division weakens evangelistic efforts and causes some to conclude that objective religious truth does not exist. If Christians cannot agree even among themselves, why should outsiders take their claims seriously? The Catholic response points to the Church’s consistent teaching across centuries and the chaos that results when people reject her authority.

Interpretive disagreement also affects the spiritual lives of believers. When people embrace erroneous interpretations of Scripture, it can lead them away from sound doctrine and holy living. False teachings about salvation, morality, or church governance can damage souls and lead people astray. History records numerous examples of how misinterpreted Scripture has been used to justify evil practices. Southern slaveholders in America cited biblical passages to defend slavery. Prosperity gospel preachers twist Scripture to promise material wealth to the faithful. Cultish movements interpret prophecy to predict the end of the world on specific dates. All these errors involve sincere people reading Scripture but arriving at conclusions that contradict truth. These mistakes demonstrate the danger of private interpretation unguided by Church authority.

The fragmentation of Protestant Christianity into thousands of denominations illustrates the practical impossibility of maintaining unity without an authoritative teaching body. Each new generation of Protestants discovers disagreements with their predecessors and splits off to form new denominations claiming to be more faithful to Scripture. This process continues endlessly because there is no authoritative voice with the power to settle disputes definitively. Individual congregations become answerable only to themselves, and charismatic leaders can lead their followers into error with no external correction. The Catholic Church, by contrast, maintains substantial unity despite being present in every culture and containing over a billion members. This unity is not perfect, as history records periods of confusion and dissent, but the Church possesses the structural means to resolve disputes and maintain doctrinal continuity. The existence of the Magisterium makes unified interpretation possible in a way that pure private judgment cannot achieve.

The Church’s Definitive Interpretations

A common misconception holds that the Catholic Church has definitively interpreted every verse of Scripture, leaving no room for discussion or scholarly inquiry. In reality, the Church has infallibly defined the meaning of relatively few specific passages. What the Church has done is to define doctrines that are based on Scripture and that provide boundaries within which interpretation must remain. For example, the Church has not provided a detailed commentary on every verse of the Gospels, but she has defined that Jesus Christ is truly God and truly man, that He rose bodily from the dead, and that He established His Church on the foundation of Peter and the apostles. These defined doctrines exclude certain interpretations while allowing significant freedom within orthodox bounds.

The Church’s approach allows for legitimate theological diversity and ongoing scholarly study. Catholic biblical scholars engage in serious academic work examining manuscripts, studying ancient languages, and proposing new insights into biblical texts. They do not all agree with one another on every point, and the Church permits this diversity as long as conclusions remain within the bounds of defined doctrine. A Catholic Scripture scholar might propose a new understanding of a particular Gospel passage’s literary structure or historical context, and other scholars may disagree, and this scholarly debate enriches the Church’s understanding. What scholars may not do is propose interpretations that contradict defined doctrine. They cannot, for instance, argue that Jesus was only a human prophet or that the resurrection was merely symbolic rather than historical.

This balance between defined doctrine and scholarly freedom reflects the Church’s wisdom in recognizing different levels of certainty. Some truths are essential to the faith and have been clearly revealed and definitively taught. Others are matters of legitimate theological speculation where the Church allows different opinions. Still others await fuller understanding as the Church continues to reflect on divine revelation under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The existence of theological diversity within the bounds of orthodoxy demonstrates that Catholic interpretation is not rigid or stifling but rather provides a framework within which authentic intellectual inquiry can flourish. The Church protects essential truths while allowing freedom in non-essential matters, maintaining unity without imposing uniformity where God has not required it.

The Path Forward

Recognizing the sources of confusion about Scripture’s meaning points toward solutions for those seeking genuine understanding. First, believers must approach Scripture with humility, acknowledging the limitations imposed by fallen human nature and the complexity of the biblical text. The person who assumes that clear reading will automatically yield correct interpretation sets himself up for error. Pride in one’s own understanding is a significant obstacle to receiving truth. Second, serious study of Scripture must include attention to historical context, literary forms, and the original languages. While not every believer can become a professional biblical scholar, all can benefit from good study resources that explain these contextual factors. Reading Scripture with awareness of how the original audience would have understood it guards against anachronistic interpretations.

Third, and most importantly, Catholic believers should read Scripture within the living tradition of the Church, guided by the Magisterium’s teaching. This means consulting the Catechism when questions arise, reading the Church Fathers to see how early Christians understood passages, and being willing to submit personal interpretations to the judgment of Church authority. It means recognizing that the Church possesses a wisdom accumulated over two millennia of reflection on Scripture under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Individual insight is valuable but must be tested against this broader wisdom. When personal interpretation conflicts with Church teaching, the proper response is to re-examine one’s own understanding rather than assuming the Church is wrong.

The witness of Catholic converts from Protestantism often includes recognition that the interpretive chaos they experienced drove them to seek an authoritative guide. After years of uncertainty about which interpretation to follow, they discovered peace in submitting to the Church’s teaching. This submission is not intellectual suicide but rather a reasonable recognition that Christ established a Church with teaching authority for precisely this purpose. The confusion about Scripture that persists outside the Church testifies to the wisdom of Christ’s provision. He did not leave believers to figure everything out individually but rather established a Church that would faithfully preserve and teach His message to every generation. Those who accept this gift of authoritative teaching find that Scripture’s meaning becomes clearer, not because every question is answered, but because they possess reliable guidance through the difficult passages and confidence that they are understanding divine revelation correctly.

Conclusion

The question of why confusion persists despite Scripture’s clarity admits a complex answer that honors both divine revelation and human limitation. Scripture is clear in the sense that God truly communicates through it and intends for His message to be understood. The essential truths necessary for salvation are accessible to all believers who approach the text with faith and good will. However, this clarity does not eliminate the need for careful interpretation, scholarly study, and authoritative guidance. The effects of original sin, the cultural and linguistic distance from the biblical world, the multiple senses of Scripture, and the complexity of biblical themes all contribute to interpretive challenges. God provided solutions to these challenges through Sacred Tradition and the Magisterium, working together with Scripture to form a complete system of divine revelation.

The Catholic approach to Scripture interpretation balances confidence in God’s revelation with humility about human limitation. It encourages personal Bible reading and meditation while providing authoritative teaching to guard against error. It permits theological diversity within defined boundaries while maintaining essential doctrinal unity. This system has preserved Christian truth for two thousand years despite cultural changes, persecution, and internal challenges. The confusion that characterizes communities lacking this authoritative guidance demonstrates its necessity. Those who seek genuine understanding of Scripture will find it not through private judgment alone but through engagement with the Church’s living tradition under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The path to clarity runs through the Church that Christ established precisely to preserve and teach His revelation to all nations until the end of time.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.