Brief Overview

- The sacramental seal means any priest who hears your confession is absolutely forbidden from revealing anything you confess, making your sins completely protected regardless of your personal relationship with him.

- When a priest hears confessions, he acts in persona Christi, meaning he represents Christ himself rather than functioning as his personal self during the sacrament.

- Catholics have the right to confess anonymously behind a screen rather than face-to-face, which can reduce feelings of awkwardness when confessing to a priest you know personally.

- Priests are trained to separate their sacramental role from their social relationships and typically do not remember specific sins confessed to them outside the confessional context.

- The discomfort you feel when confessing to a priest you know socially is a common experience that does not invalidate the sacrament or make your confession less worthy.

- Seeking confession from a priest at another parish or during times when multiple priests are available provides practical options for those who prefer greater anonymity in the sacrament.

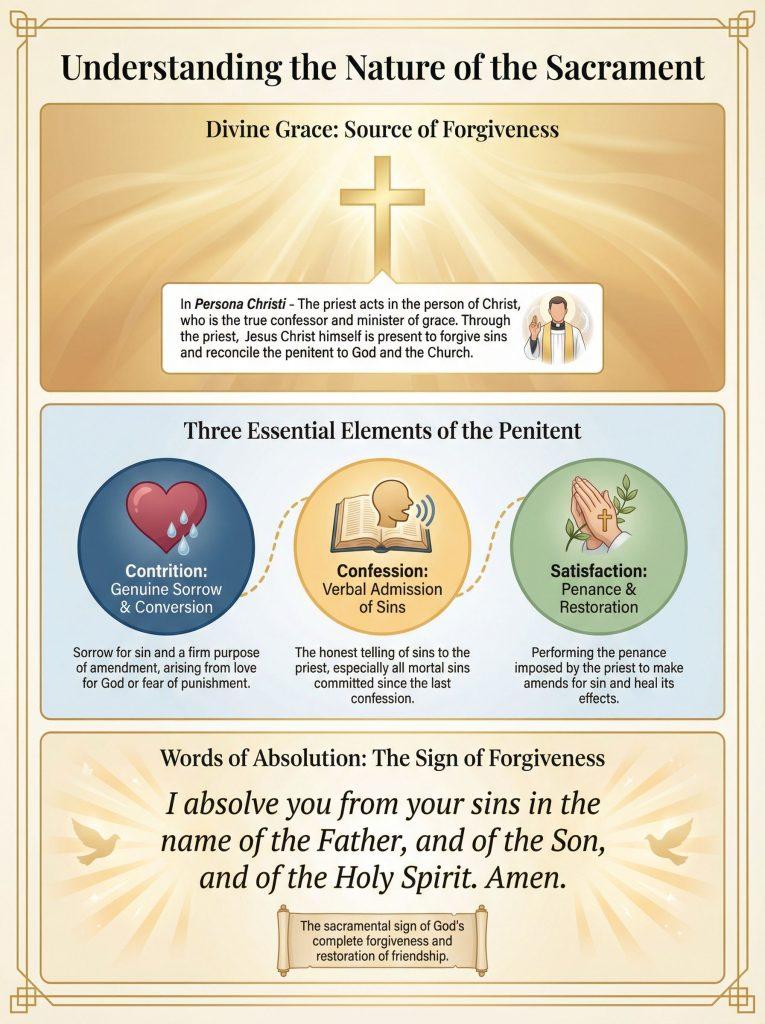

Understanding the Nature of the Sacrament

The Sacrament of Reconciliation stands as one of the seven sacraments established by Christ for the spiritual healing and restoration of his followers. When you approach this sacrament with a priest you know socially, you must first understand what actually happens during confession from a Catholic perspective. The priest does not hear your sins as himself but rather as an instrument of Christ, acting in persona Christi. This Latin phrase means “in the person of Christ” and indicates that the priest’s personal identity becomes secondary to his sacramental role. When he sits in the confessional or reconciliation room, he functions as Christ’s representative on earth, exercising the power that Jesus gave to his apostles in John 20:21-23. Christ appeared to his disciples after the resurrection and breathed on them, saying they had the power to forgive sins or retain them. This power passed through apostolic succession to the bishops and priests of today. The priest hearing your confession essentially disappears as an individual person, becoming instead a conduit for God’s mercy and forgiveness. Understanding this theological reality helps address the awkwardness because you are not truly confessing to Father John or Father Michael as your friend or acquaintance; you confess to Christ himself through the ministry of his Church.

The essential nature of the sacrament requires your participation through three actions that Catholic teaching identifies as contrition, confession and satisfaction. Contrition means genuine sorrow for your sins and a firm purpose of amendment, which involves resolving not to commit those sins again. Confession refers to the actual verbal admission of your sins to the priest, which the Church teaches as necessary for the forgiveness of mortal sins (CCC 1456). Satisfaction involves performing the penance assigned by the priest, which helps repair the damage caused by sin and restores your relationship with God and the Church. These three elements work together with the priest’s absolution to complete the sacrament. The absolution itself comes not from the priest’s personal power but from Christ working through him. When the priest says “I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” he speaks these words with Christ’s authority, not his own. The formula of absolution used in the Latin Church makes clear that God the Father remains the source of all forgiveness, accomplished through Christ’s death and resurrection and communicated through the Holy Spirit. The priest serves as the visible minister of this invisible grace, making concrete and tangible what would otherwise remain abstract and uncertain.

The Protection of the Sacramental Seal

The Catholic Church protects what you confess through the sacramental seal, which stands as one of the most absolute and inviolable laws in all of Church teaching. The Catechism states unequivocally that every priest who hears confessions remains bound under very severe penalties to keep absolute secrecy regarding the sins his penitents confess to him (CCC 1467). This seal admits of no exceptions whatsoever. A priest cannot break it to save his own life, to protect his reputation, to prevent a crime, to testify in court or for any other reason imaginable. Canon Law 983 reinforces this teaching by declaring the sacramental seal inviolable and absolutely forbidding a confessor from betraying a penitent in any way, whether through words or any other manner, for any reason. The penalties for violating this seal include automatic excommunication reserved to the Holy See, meaning only the Pope can lift it. This represents one of the most severe penalties the Church can impose, demonstrating how seriously the Church takes the confidentiality of confession. The seal covers not only what you explicitly confess but also anything the priest learns through your confession, including the fact that you went to confession at all.

Canon Law 984 extends this protection further by forbidding the confessor from using knowledge acquired in confession to the detriment of the penitent, even when all danger of disclosure has been excluded. This means a priest cannot act on information he learns in confession, even indirectly. If you confess to embezzling money from your employer and the priest happens to be friends with that employer, he cannot warn the employer or treat you differently based on that knowledge. If you confess to having committed a serious crime, the priest cannot report it to authorities or even suggest to others that they should investigate you. The knowledge remains sealed in the confessional, unable to be used in any context outside of it. This protection extends even to situations where revealing the information might prevent harm to others. The Church has consistently taught that the sacramental seal takes precedence over all other considerations, including civil law requirements to report certain crimes. Priests in various countries have gone to prison rather than violate the seal, and the Church supports them in this decision. When you confess to a priest you know socially, this same absolute protection applies without any diminishment or qualification.

The seal protects you so thoroughly that priests typically report they cannot remember most confessions they hear. This phenomenon occurs partly because priests hear many confessions and partly because they train themselves to forget what they hear as a protection of the seal. Many priests describe the experience of sitting in the confessional as entering a different mental and spiritual space where they focus entirely on being Christ’s instrument rather than storing memories as they would in normal conversation. After absolution, the sins you confessed essentially cease to exist for the priest in any meaningful way. He cannot gossip about them, think about them when he sees you at parish events, make judgments about you based on them or allow them to influence how he interacts with you socially. The seal creates a complete separation between what happens in confession and what happens in the rest of the priest’s ministry and social life. This separation means that when you see the priest at a parish picnic or run into him at the grocery store, he relates to you without any reference to what you confessed. Your sins remain known to God alone, erased from the priest’s functional memory and unable to affect your relationship with him in any other context.

The Right to Anonymous Confession

Catholic teaching and practice give you an absolute right to confess anonymously, which provides a practical solution to the awkwardness of confessing to a priest you know. Traditional confessionals include a screen or grill that prevents the priest from seeing who confesses on the other side. Modern reconciliation rooms typically contain two options for confession. One side has a chair where you can sit face-to-face with the priest if you choose. The other side includes a kneeler with a screen, allowing you to kneel and confess without the priest seeing your face. Church law requires that priests make the anonymous option available to all penitents who desire it. Canon Law gives penitents the right to choose how they confess, whether behind a screen or face-to-face, and priests must respect this choice. If a parish only offers face-to-face confession without providing a screen option, this violates Church law and the rights of the faithful. You can and should request anonymous confession if that makes you more comfortable, and the priest must accommodate this request.

When you use the screen option, you maintain complete anonymity if you choose. You need not identify yourself by name, and the priest cannot see your face through the screen. While some priests might recognize voices, particularly if they know you very well, the seal still binds them completely to secrecy and forgetfulness. Many Catholics who know their priest socially find that confessing behind a screen removes most of the awkwardness from the experience. The physical barrier creates psychological distance that makes the confession feel more private and less personal. You can speak your sins to Christ through his minister without the added emotional weight of making eye contact with someone you will see at the church fundraiser next week. The screen also helps the priest maintain his role as confessor rather than friend, reinforcing the sacramental nature of the encounter. Some people worry that using the screen seems unfriendly or suggests they have something to hide, but this concern misunderstands the purpose of the screen. The screen exists precisely to protect the sacramental encounter and allow penitents to confess freely without social pressure or embarrassment.

The choice between face-to-face and anonymous confession remains entirely yours to make based on your comfort level and spiritual needs. Neither option makes your confession more or less valid or pleasing to God. Some people prefer face-to-face confession because they find it more personal and relational, feeling that it better expresses the personal nature of sin and reconciliation. Others prefer the screen because it allows them to focus entirely on their sins and their relationship with God without the distraction of social dynamics. Both approaches have value, and neither represents a superior form of the sacrament. The Church wisely provides both options, recognizing that different people have different needs and that the same person might prefer different approaches at different times. When you feel awkward about confessing to a priest you know, choosing the anonymous option eliminates most of that awkwardness while preserving the full grace and validity of the sacrament. You lose nothing essential by choosing the screen, and you gain the peace of mind that comes from greater privacy in a vulnerable moment.

The Priest’s Perspective and Training

Priests receive extensive training in how to administer the Sacrament of Reconciliation, including specific instruction on maintaining appropriate boundaries between their sacramental role and their personal relationships. Seminary formation includes both theological education about the nature of the sacrament and practical training in hearing confessions. Priests learn to cultivate what might be called a “confessional mindset” that helps them separate what they hear in confession from their other interactions with penitents. They practice entering a prayerful, receptive state when they sit down to hear confessions, consciously setting aside their personal reactions and judgments. They learn to focus on providing sound spiritual advice, assigning appropriate penances and conveying God’s mercy rather than storing up information about the people who confess to them. This training helps them fulfill their responsibility under the seal while also maintaining healthy relationships with parishioners outside the confessional. Many priests report that this separation becomes second nature over time, making it genuinely difficult for them to remember specific confessions even if they wanted to, which they do not.

The spiritual and psychological discipline required to maintain this separation represents a significant aspect of priestly ministry that laypeople often underestimate. When a priest hears confessions week after week, sometimes for decades, he develops the capacity to hold what he hears lightly, allowing it to pass through his consciousness without leaving permanent traces. Some priests describe it as similar to water flowing through a pipe; the water moves through but does not become part of the pipe itself. Others compare it to being a channel or vessel for God’s grace, where they remain open but not retaining. These metaphors capture something important about how priests experience their role in confession. They must be present and attentive enough to provide good counsel and assign appropriate penance, but they must also maintain enough detachment to forget what they hear once the absolution has been given. This balance requires both natural aptitude and deliberate cultivation through prayer and practice. Priests who struggle with remembering confessions often develop specific techniques to help themselves forget, such as immediately praying for the penitent in a general way without rehearsing the specific sins confessed.

Understanding the priest’s perspective can help reduce your awkwardness about confessing to someone you know socially. From the priest’s side, hearing your confession does not change how he thinks about you or relates to you outside the confessional. He does not go home and reflect on what you told him or form judgments about your character based on your sins. He does not feel uncomfortable seeing you at parish events or worry about what you think he thinks about you. Most priests genuinely experience the separation between confession and other contexts as complete and automatic. When Father Smith chats with you after Mass about the upcoming parish festival, he relates to you as a fellow parishioner and friend without any consciousness of what you may have confessed to him. The seal operates not just as an external rule he follows but as an internal reality that shapes how he processes and stores information. This means your worry about whether he remembers your sins or judges you for them addresses a concern that simply does not match the priest’s actual experience. He almost certainly does not remember, and even if some fragment of memory remains, the seal prevents it from affecting his relationship with you in any way.

Practical Strategies for Managing Awkwardness

Several practical approaches can help you manage the awkwardness of confessing to a priest you know, allowing you to receive the sacrament without unnecessary emotional distress. The first and simplest strategy involves taking advantage of the anonymous confession option discussed earlier. If your parish offers traditional confessionals with screens or reconciliation rooms with privacy screens, use them without hesitation or embarrassment. Arrive a few minutes early for scheduled confession times to ensure you get to use the anonymous side of the reconciliation room if multiple penitents are waiting. Some parishes have two separate entrances to the reconciliation room, one for face-to-face and one for anonymous confession, making the choice easy and obvious. Other parishes have a single entrance with options inside, requiring you to choose once you enter. In either case, do not feel pressured to choose face-to-face simply because you know the priest or because you think it seems more mature or advanced. Choose what allows you to confess honestly and completely without the barrier of social awkwardness.

A second strategy involves seeking confession from priests at neighboring parishes or from visiting priests who hear confessions at your parish during special times. Canon law guarantees all Catholics the freedom to confess their sins to any legitimately approved confessor of their choice, not just their own parish pastor. You can attend confession times at a nearby parish where you do not know the priest personally, receiving the same sacramental grace without the social complication. Many Catholics adopt this practice regularly, particularly in areas with multiple parishes close together. Some people rotate between several different parishes for confession, while others establish a regular practice of going to one nearby parish specifically for this sacrament while remaining active members of their home parish for other activities. This approach does not represent disloyalty to your parish or suggest anything wrong with your pastor. It simply recognizes that different sacramental settings serve different spiritual needs. You might also take advantage of special confession times during Advent and Lent when dioceses often bring in extra priests to hear confessions. These visiting priests have no social connection to you and will not see you again after that particular confession, eliminating the awkwardness entirely.

Some Catholics find it helpful to establish a relationship with a regular confessor at another parish, someone they see only in the context of confession. This practice, common in Catholic tradition, involves choosing a priest who knows you spiritually through confession but not socially through other contexts. You might schedule confession by appointment with this priest monthly or quarterly, developing a confessional relationship without a social one. The priest comes to know your spiritual struggles and patterns over time, allowing him to give more targeted advice and accompaniment, but you never see him at social events or casual parish gatherings. This arrangement combines the benefits of regular confession to the same priest with the freedom from social awkwardness. When scheduling such appointments, you need not explain your reasons for coming to that particular parish instead of your own. Simply call the parish office, ask about scheduling confession and arrive at the appointed time. Most priests appreciate when people take confession seriously enough to schedule it rather than treating it as a quick obligation squeezed in between other activities.

The Spiritual Benefits of Overcoming Awkwardness

Working through the awkwardness of confession, rather than always avoiding it, can produce significant spiritual growth and deeper trust in God’s mercy. The discomfort you feel when confessing sins to another human being, even one bound by the seal and acting in Christ’s person, serves as a form of penance itself. This discomfort humbles you and makes concrete the reality that sin affects not just your private relationship with God but your relationship with the Church as the Body of Christ. Catholic teaching understands confession as having both a vertical dimension, reconciling you with God, and a horizontal dimension, reconciling you with the Church community (CCC 1440). When you confess to a priest you know socially, the horizontal dimension becomes more vivid and immediate. You experience in a tangible way the truth that your sins wound not just your soul but the entire Body of Christ, represented by this specific member of Christ’s body who sits before you. The awkwardness, uncomfortable as it feels, can deepen your understanding of sin’s communal nature and the importance of reconciliation within the Church.

Furthermore, continuing to confess to your parish priest despite the awkwardness can strengthen your faith by requiring you to trust more completely in the sacramental system Christ established. When confession feels easy and anonymous, you might rely partly on the privacy and distance to make you feel safe enough to confess. When confession feels awkward because you know the priest socially, you must rely more fully on your faith in the sacramental seal, the priest’s integrity and Christ’s presence in the sacrament. This deeper trust represents genuine spiritual maturity. You move beyond depending on your own comfort level and instead depend entirely on God’s promise that this sacrament accomplishes what it signifies. The vulnerability required to confess face-to-face to someone you know mirrors the vulnerability required in other aspects of spiritual life. You cannot grow spiritually while constantly protecting yourself from all discomfort and awkwardness. Sometimes God calls you to step into uncomfortable situations precisely because doing so strengthens your faith and trust.

Many Catholics who initially found it very awkward to confess to their parish priest report that the awkwardness diminished significantly over time as they experienced repeatedly that their fears did not materialize. The priest did not treat them differently after confession, did not make knowing remarks or give special looks, did not seem to remember what they had confessed at all. These repeated experiences of the seal’s protection and the priest’s professionalism gradually built trust and reduced anxiety. After confessing several times to the same priest, the initial awkwardness transformed into a comfortable familiarity with the process and confidence in the sacrament’s protective structure. This progression suggests that always avoiding the awkwardness by going elsewhere might prevent you from experiencing this growth in trust and confidence. Sometimes the spiritual benefit lies not in eliminating the awkwardness but in persisting through it until it loses its power over you. Of course, this does not mean you must always confess to your parish priest or that doing so represents a superior spiritual choice. Rather, it means you should not let awkwardness alone prevent you from confessing to him if that would otherwise be the most convenient or appropriate option.

Theological Foundations for Confidence

The theological foundation for confidence in confession rests on Christ’s institution of the sacrament and his promise that the Church’s power to forgive sins comes directly from him. After his resurrection, Jesus appeared to his disciples and gave them the Holy Spirit along with the authority to forgive sins, as recorded in John 20:21-23. This authority did not originate with the apostles themselves or with the Church they would build but came directly from Christ as part of his redemptive work. When you confess your sins to a priest, you participate in this two-thousand-year chain of sacramental grace extending back to that moment when the risen Christ breathed on his apostles. The priest’s authority to absolve your sins derives not from his personal holiness, his psychological insight or his social status but solely from his ordination and the authority Christ gave to his Church. This means that even if you feel awkward confessing to a priest you know, even if you question his personal judgment or have concerns about his character in other areas, his ability to validly absolve your sins remains unchanged. The sacrament works ex opere operato, meaning by the very fact of the action being performed, not depending on the minister’s personal worthiness.

The Catholic understanding of sacramental character helps explain how this works. When a man receives the Sacrament of Holy Orders, he receives an indelible spiritual mark that configures him to Christ and gives him the permanent power to act in Christ’s person in certain sacraments. This character remains regardless of the priest’s personal holiness or lack thereof, his social relationships or his state of grace. A priest in mortal sin can still validly celebrate Mass and hear confessions, though he sins by doing so without first confessing his own sins. This reality sometimes troubles people, but it actually provides tremendous pastoral comfort. You need not investigate a priest’s personal life or spiritual condition before confessing to him. You need not wonder whether his sins make your absolution invalid or less effective. The sacrament’s validity depends on Christ’s promise and the Church’s authority, not on the particular priest’s sanctity. This theological principle becomes especially important when confessing to a priest you know socially, because you might be aware of his flaws, weaknesses and sins in ways you would not be with a stranger. Knowing that his human limitations do not diminish the sacrament’s power frees you from worry about whether he measures up to some imagined standard of perfection.

Catholic teaching about the Church as the mystical Body of Christ further grounds your confidence in confession. When you confess to a priest, you confess not just to an individual minister but to the Church herself, which acts through her ordained ministers (CCC 1448). The Church serves as the sign and instrument of the forgiveness Christ won for us by his death and resurrection. She makes visible and concrete what might otherwise remain invisible and abstract. The priest represents not just Christ but the entire Church community, welcoming you back into full communion after sin has damaged your relationship with the body. This ecclesial dimension means that your confession involves more than just a transaction between you and the priest. It involves the entire Church praying for you, doing penance with you and celebrating your return to full communion. Keeping this larger reality in mind helps put the social awkwardness in proper perspective. Yes, you feel uncomfortable confessing to Father John because you see him at parish events and know his family. But Father John in that moment represents far more than himself; he represents Christ and the Church, and your confession accomplishes far more than just revealing embarrassing information to someone you know.

Addressing Common Concerns and Misconceptions

One common concern about confessing to a priest you know involves worrying that he will judge you or think less of you after hearing your sins. This concern misunderstands both the nature of the sacrament and the typical experience of priests who hear confessions. Priests hear such a wide variety of sins from so many different people that they develop a realistic understanding of human weakness and the universality of sin. Nothing you confess will shock them or lead them to single you out as particularly wicked. They have heard worse sins than yours from people who seem more pious than you. More importantly, priests understand that the sins confessed represent only one aspect of a person’s spiritual life. They know that the fact you came to confession demonstrates repentance, humility and desire for God, which matters far more than the specific sins you committed. The priest sees you in confession at what might be your most honest and vulnerable moment, which tends to inspire respect and compassion rather than judgment and contempt. Many priests report that hearing confessions actually increases their love and respect for their parishioners because they witness people’s courage in facing their sins and their trust in God’s mercy.

Another misconception involves thinking that priests remember specific confessions and feel awkward around you afterward because they know your sins. As explained earlier, priests generally do not remember specific confessions due to a combination of factors including the sheer volume of confessions they hear, their training to forget and the psychological protection of the seal. Even if a priest does retain some memory of your confession, the seal prevents him from allowing it to affect his behavior toward you. He cannot act on that knowledge in any way, meaning he must relate to you exactly as he would if he had never heard your confession. This creates a functional equivalence to genuinely forgetting, because the information cannot influence his actions. The awkwardness you fear feeling around the priest after confession almost always turns out to be one-sided. You might feel self-conscious wondering if he remembers, but he either genuinely does not remember or acts in ways indistinguishable from not remembering. After a few interactions where nothing seems different, most people realize their worry was unfounded and the awkwardness dissipates.

Some people worry about the possibility, however remote, that a priest might somehow violate the seal despite its absolute protection under Church law. While such violations have occurred in history, they remain extraordinarily rare because priests understand the severe consequences both canonical and spiritual. A priest who violates the seal incurs automatic excommunication and faces removal from ministry. Beyond these external penalties, priests who take their vocation seriously recognize that violating the seal would constitute a profound betrayal of Christ and the people entrusted to their care. The seal exists not primarily as a restriction imposed on priests but as a protection for penitents and a safeguard of the sacrament’s integrity. Priests learn to view the seal as a sacred trust rather than a burden. If you remain concerned about a particular priest’s trustworthiness, you have the right to confess to a different priest; Church law does not require you to confess to your pastor or any specific priest. However, centuries of Catholic practice demonstrate that the seal works effectively to protect penitents, and trusting in this protection forms part of trusting in the Church Christ established.

The Role of Regular Confession

Establishing a regular pattern of confession can significantly reduce the awkwardness factor over time by making confession a normal part of your spiritual routine rather than a rare and therefore more emotionally charged event. Many spiritual directors recommend monthly confession for Catholics seeking to grow in holiness, regardless of whether they have committed mortal sins requiring confession. Regular confession allows you to address patterns of venial sin before they become entrenched, receive regular spiritual counsel and remain close to the sacrament’s graces. When you confess regularly, each individual confession carries less emotional weight. You do not build up months or years of sins that make confession feel overwhelming. You do not attach as much anxiety to the experience because it happens frequently enough to become familiar and less frightening. Regular confession also helps normalize your relationship with the priest as confessor, making it easier to distinguish between his role in confession and his role in other contexts.

The practice of regular confession with the same priest over time can create a fruitful spiritual relationship even when that priest is someone you know socially. The priest comes to understand your spiritual struggles and patterns, allowing him to offer more specific and helpful counsel. He can notice when you make progress in overcoming particular sins and encourage you in that growth. He can also notice when you fall back into old patterns and challenge you to examine what circumstances or attitudes contribute to those falls. This kind of pastoral accompaniment represents one of confession’s underappreciated benefits, possible only when you confess regularly to the same priest rather than constantly seeking out strangers. While the sacrament remains valid regardless of whether the priest knows your spiritual history, the additional dimension of accompaniment can deepen the sacrament’s transformative power in your life. The social awkwardness you initially felt confessing to this priest you know gives way to spiritual fruitfulness as the confessional relationship develops.

Developing a regular confession schedule also demonstrates to yourself and to God your commitment to the spiritual life and your willingness to take responsibility for your sins. When you confess only when required or when guilt becomes unbearable, confession feels more like a crisis intervention than a path of growth. When you confess regularly according to a schedule, confession becomes part of your spiritual discipline like daily prayer or weekly Mass attendance. This shift in perspective changes how you approach the sacrament. You come not primarily out of crisis or compulsion but out of commitment to spiritual growth and desire for God’s grace. This more positive motivation often reduces anxiety and awkwardness because you are not in crisis mode, and you view the priest more as a spiritual companion than as someone before whom you must humiliate yourself. The regularity itself creates familiarity that reduces fear. Just as people who attend daily Mass often find it more peaceful and less intimidating than those who attend only on Sundays, people who confess regularly often find it less awkward than those who confess rarely.

Balancing Anonymity and Personal Accompaniment

The tension between desiring anonymity and benefiting from personal accompaniment represents one of the practical challenges Catholics face regarding confession. On one hand, the anonymous confession option provides relief from social awkwardness and allows complete freedom in confessing without worrying about social consequences. On the other hand, confessing regularly to the same priest who knows your spiritual history allows for deeper guidance and more personalized counsel. Some Catholics resolve this tension by having both a regular confessor for routine monthly confession and maintaining the option to seek anonymous confession elsewhere for particularly sensitive or embarrassing sins. This approach combines the benefits of spiritual accompaniment with the freedom to confess difficult matters without social complication. While some spiritual directors criticize this practice as avoiding necessary humility, others recognize it as a legitimate pastoral accommodation to human weakness.

Another approach involves choosing a regular confessor who lives far enough away that you never see him in social contexts but close enough that you can visit him regularly for confession by appointment. This arrangement provides spiritual accompaniment without social awkwardness, though it requires more effort and planning than simply going to confession at your parish during regular times. Some Catholics establish such relationships with priests at monasteries, shrines or retreat centers they visit periodically. The distance creates natural separation between the confessional relationship and daily life, while the regularity builds the trust and familiarity that enables deeper spiritual direction. This option works particularly well for people whose work or other circumstances take them regularly to a location where such a confessor can be found. For instance, someone who travels monthly to a nearby city for work might establish a regular confession time with a priest there, creating a confessional relationship entirely separate from parish life at home.

A third approach involves confessing regularly to your parish priest despite the initial awkwardness, trusting that time and repeated experience will reduce the discomfort to manageable levels. Many Catholics who chose this path report that within a few months the awkwardness largely disappeared as they experienced the seal’s protection and realized the priest truly did not treat them differently based on what he heard in confession. The initial vulnerability of this approach yields long-term benefits both in spiritual accompaniment and in the practical convenience of being able to confess at your own parish without traveling elsewhere. This choice requires courage and trust but can result in significant spiritual growth. The awkwardness itself becomes a form of asceticism, a small suffering offered to God in pursuit of holiness. Over time, the relationship with your confessor can become one of the most important spiritual relationships in your life, marked by mutual respect, deep trust and focused on the single goal of your sanctification and union with Christ.

The Importance of Moving Forward

Regardless of how you choose to address the awkwardness of confessing to a priest you know, the most important thing remains that you continue to make use of this sacrament regularly and honestly. The enemy of souls wants nothing more than to keep you away from confession through fear, shame or awkwardness. Do not allow social discomfort to prevent you from receiving the grace God offers through this sacrament. If confessing to your parish priest feels too awkward, find another priest. If face-to-face confession makes you too self-conscious, use the anonymous option. If monthly confession feels too frequent to sustain your courage, start with quarterly confession. Make whatever practical accommodations you need to ensure that you actually go to confession rather than perpetually planning to go but never quite making it happen. The perfect confession setup that you never use helps you far less than the imperfect setup that gets you into the confessional regularly.

Remember that the awkwardness, while real, represents a relatively minor consideration in light of what confession accomplishes in your soul. This sacrament removes the guilt of mortal sin, restores sanctifying grace, reconciles you with God and the Church, strengthens you against future temptation and provides spiritual counsel for your growth in holiness. These benefits far outweigh the temporary discomfort of confessing to someone you know. Your eternal salvation matters infinitely more than avoiding an awkward social situation. When you stand before God in judgment, you will not regret the awkwardness you endured to make use of this sacrament, but you might deeply regret times you stayed away from confession out of mere social anxiety. Keeping this eternal perspective helps put the awkwardness in its proper place as a real but ultimately minor obstacle to something of infinite importance.

The awkwardness of confessing to a priest you know socially represents a common human experience that the Church addresses through both theological principles and practical accommodations. The sacramental seal provides absolute protection, the priest acts in persona Christi rather than as himself, anonymous confession remains your right, and multiple options exist for managing the social dimension of the sacrament. None of these solutions requires you to pretend the awkwardness does not exist or to feel guilty for experiencing it. Rather, they acknowledge the legitimate difficulty while providing ways to move forward in receiving this tremendous gift of God’s mercy. Your sins, no matter how embarrassing or serious, can be forgiven in an instant through this sacrament. The price Christ paid for that forgiveness was his life on the cross; the price you pay includes at most a few minutes of social awkwardness. This perspective should give you courage to approach the confessional with confidence, trusting in God’s mercy and the Church’s wisdom in establishing this sacrament.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.