Brief Overview

- The Reddit post raises challenges about God’s omnipotence, omniscience, and perfect love that Catholic theology has addressed in detail for centuries through careful philosophical and theological reasoning.

- The Catholic Church teaches that God’s omnipotence does not mean God can perform acts that are logically self-contradictory, such as simultaneously granting genuine free will and forcing creatures to choose rightly (CCC 268).

- The existence of evil and suffering in the world does not logically disprove a good and powerful God; rather, the Catholic tradition argues that free will and the ordering of creation toward a greater good explain why suffering exists.

- The doctrine of the Holy Trinity, far from being a logical impossibility, rests on a careful distinction between one divine nature and three distinct Persons, which the Church has articulated through centuries of theological reflection (CCC 253).

- The Catholic teaching on hell presents it not as a punishment arbitrarily inflicted by a vengeful God but as the permanent consequence of a person’s own free and final rejection of God’s love (CCC 1033, 1037).

- The Reddit post’s use of Psalm 115:4-8 against God is actually a passage directed against lifeless material idols, and Catholic theology makes a clear distinction between the living, transcendent God and the kind of silent, handmade objects this psalm describes.

Original Reddit Post from r/exChristian:

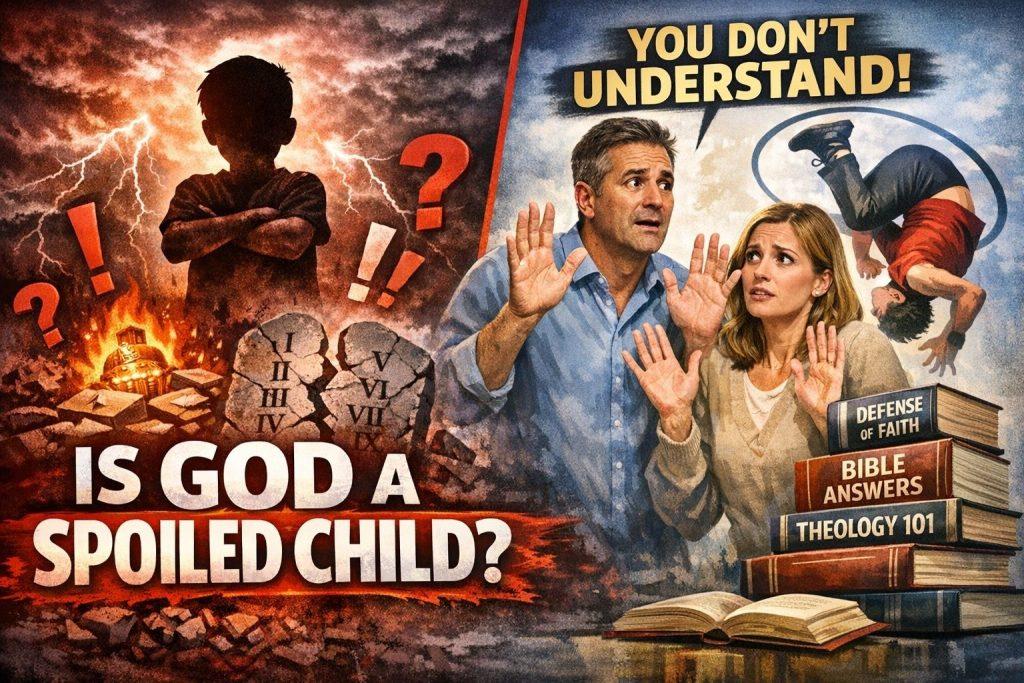

God is like a spoiled child, while Christians are like god’s helicopter parents

God is like a spoiled child who can only be praised and can never be blamed. Meanwhile Christians are like god’s helicopter parents who boast about their “precious and flawless” child. They claim god is all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-loving, yet when someone points out that their god fails to do what they claim him to be, they simply make up excuse for him:

“You simply don’t understand him.”

“How dare you ever question god’s performance?”

“You shouldn’t expect god to meet your expectation.”

“You must believe what god can do.”If you change the word “god” to “my child,” they sound exactly like what helicopter parents would say. So rather than protecting god from all the criticisms, why don’t Christians let their precious god proof himself instead? Tell him to stop hiding from now on, tell him to show up during apologetic debates, tell him to do something to prevent disasters, tell him to hold a press conference to answer all the questions like “Why don’t god destroy the devil in the first place if he can foresee the future?” Or “How can a god be “three persons” while remain as one god?” Or “Why would a all-loving god send people to be tortured for eternity for simply not believing him?”

I’ll end this with Psalm 115:4-8.

But their idols are silver and gold, made by human hands. They have mouths, but cannot speak, eyes, but cannot see. They have ears, but cannot hear, noses, but cannot smell. They have hands, but cannot feel, feet, but cannot walk, nor can they utter a sound with their throats. Those who make them will be like them, and so will all who trust in them.

Understanding What the Post Is Really Arguing

The Reddit post makes a comparison between God and a spoiled child, and between Christians and overprotective parents who refuse to hold their child accountable. It is worth taking this analogy seriously before responding, because it contains a genuine emotional frustration that many people feel when faith seems to offer no verifiable results. The author is essentially arguing that Catholic defenses of God amount to nothing more than excuse-making and that a truly powerful, truly loving, and truly knowing God would make himself obvious in ways the world could plainly see. This kind of challenge is not new, and Catholic theologians from Augustine of Hippo to Thomas Aquinas to contemporary figures like Peter Kreeft have engaged it directly and rigorously. The post is not simply an emotional complaint; it raises four distinct philosophical questions that deserve careful attention. Those questions are whether God’s omnipotence is real, whether the existence of evil disproves God, whether the Trinity is logically coherent, and whether eternal consequences for rejecting God are just. Each of these questions has well-developed Catholic answers rooted in Scripture, reason, and the Church’s living tradition. The post also ends with a quotation from Psalm 115:4-8, which the author turns against Christianity itself, suggesting that the God Christians worship is no different from the speechless, sightless idols that the psalm mocks. Addressing all of these points requires some patience and precision, because several of the post’s assumptions rest on misunderstandings of what the Catholic faith actually claims about God. The goal here is not to dismiss the frustration behind the post but to show that the Catholic answers to these questions are not mere evasions; they are grounded in centuries of careful, honest thinking.

What Catholics Actually Mean When They Say God Is All-Powerful

The most common misreading of Catholic teaching on divine omnipotence is the assumption that “all-powerful” must mean “able to do literally anything that can be imagined.” The Catholic Church does not teach this, and has never taught this. The Catechism of the Catholic Church makes this clear when it states that God’s power is universal but also notes that God’s almighty power is in no way arbitrary, because in God, power, essence, will, intellect, wisdom, and justice are all identical (CCC 271). This means that God cannot act against his own nature, which includes his perfect reason and his perfect goodness. Thomas Aquinas, whose thought the Church regards as a reliable guide in philosophy and theology, argued that when people say God cannot do something logically self-contradictory, this is not a limitation of his power but simply the recognition that the thing described is not actually a real possibility at all. For example, it would not be a show of power but a logical absurdity to say God could create a circle that is also a square, or to grant creatures authentic free will and simultaneously remove that free will at the moment of choice. The Catechism directly addresses the relationship between God’s power and his fatherly care by describing how God reveals his omnipotence precisely through mercy and forgiveness (CCC 270, 277). The reason this matters for the Reddit post is that the post assumes God’s failure to intervene in every disaster, or to appear visibly at every debate, proves he lacks power or love. But Catholic theology explains that a God who constantly overrides natural causes and human choices to prevent every bad outcome would not be acting powerfully in any meaningful sense; he would simply be running a controlled simulation without real creatures. God’s power, as the Church understands it, is shown most fully not in constant supernatural intervention but in creating a world of genuine creatures with genuine freedom and genuine consequences, and in his ability to bring good out of even the worst events. The Catechism even acknowledges that God can seem absent or incapable of stopping evil, but it insists that this apparent powerlessness is itself part of the mystery revealed through Christ crucified (CCC 272). Christians are not making excuses when they say God’s ways are not always visible; they are pointing to a consistent and coherent theological understanding of what divine power actually means. This is a substantive philosophical position, not a deflection.

The Problem of Evil: Why It Does Not Logically Disprove God

The intellectual version of the post’s complaint about God allowing disasters is called the problem of evil, and it is one of the most discussed questions in the history of philosophy. The argument, in its simplest form, says that if God is truly all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-loving, then no evil should exist, and since evil clearly does exist, God as described cannot exist. Catholic theology has engaged this argument thoroughly and honestly. The first response is what philosophers call the free will defense, which points out that authentic love and genuine goodness require a creature who can genuinely choose. A God who created beings capable only of pre-programmed obedience would not have created anything truly good or truly loving, because goodness and love require the real possibility of their opposites. The great Catholic convert and writer C.S. Lewis captured this well by noting that if you choose to say God can give a creature free will and at the same time withhold free will from it, you have not succeeded in saying anything sensible about God. Catholic teaching reflects this same insight (CCC 268). The second response involves what theologians call a wider perspective on suffering, the recognition that a being with infinite knowledge may allow short-term suffering because of long-term goods that humans, with their limited vantage point, cannot fully see. The Catechism describes God as master of history, governing hearts and events in keeping with his will (CCC 269), which implies a purpose behind events that is not always visible to people in the middle of them. The third response is that the existence of evil, far from disproving God, actually points toward him, because the very concept of evil as “bad” or “wrong” requires a moral standard, and a moral standard requires a moral lawgiver. The person who says God is wrong to allow suffering is implicitly appealing to a standard of goodness that only makes sense within a framework that includes God. Without God, there is no basis for calling anything objectively evil; events simply happen, and no framework exists for calling any of them a failure. Catholic teaching therefore does not hide from the problem of evil but engages it openly and argues that a world with real freedom, real consequences, and real meaning is more coherent with a loving God than a sanitized world of forced harmony would be.

Why God Does Not Simply Appear at Press Conferences or Debates

The post’s suggestion that God should “show up during apologetic debates” or “hold a press conference” reflects a genuine desire for certainty, and that desire is understandable. However, the Catholic faith offers a clear and reasoned account of why God does not operate this way, and it goes beyond simply saying “that’s not how God works.” The Catholic tradition teaches that faith is a gift that involves genuine human choice, and that a God who made his existence coercively obvious would effectively eliminate the possibility of genuine faith. Faith, as the Catechism explains, is a free human act responding to God’s free gift of self-revelation (CCC 143, 150). If God appeared visibly at every debate and made his existence impossible to deny, the resulting “belief” would not be the freely chosen trust that characterizes genuine faith; it would simply be an involuntary recognition of an overwhelming force. This is not an arbitrary design choice; it reflects the Catholic understanding that God desires a relationship with his creatures that is freely entered into, not a system of coercion that produces compliance. The Church also teaches that God has, in fact, revealed himself clearly through Creation, through the history of Israel, through the person of Jesus Christ, and through the living community of the Church (CCC 50-53). The Catechism states that the natural world itself is a kind of first revelation of God, accessible to human reason (CCC 32). St. Paul makes this point in Romans 1:20, writing that God’s eternal power and divine nature have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. Catholic teaching also points to the interior life, the experience of conscience and moral awareness, as a form of God’s ongoing communication with human beings (CCC 1776). None of this means God’s existence is obvious or that doubt is unreasonable; Catholic theology fully acknowledges that God’s presence is not always felt and that the experience of his silence is real and sometimes painful. But the Church maintains that this silence is not the silence of an absent or indifferent being; it is the silence that respects human freedom and invites a freely chosen response.

Why God Did Not Simply Destroy the Devil

The post asks why God did not simply destroy the devil at the outset, given that he could foresee all the harm the devil would cause. This is a genuine theological question, and Catholic teaching addresses it in a way that goes beyond a simple “God has his reasons.” The Catechism teaches that the devil is a fallen angel, a creature who was created good by God but who through his own free will turned definitively against God (CCC 391). The key word here is “free will.” Just as God does not force human beings to choose good, God did not prevent the angel who became the devil from making his free choice. To have done so would have been to create a being incapable of genuine freedom, which would mean creating something less than a fully real rational being. The Catechism is also clear that God did not create evil and is not the author of it; evil enters the world through the misuse of freedom by created beings (CCC 311). The question of why God permits the devil to continue operating rather than simply annihilating him is related to the broader question of why God permits evil at all. Catholic theology answers that God, whose wisdom and power are infinite, is able to draw good out of even the worst evils, as Romans 8:28 states. The continued existence of the devil, while clearly a source of harm, does not place God in a position of helplessness; it places God in a position of patient governance over a creation in which real freedom is taken seriously. It is also worth noting that the Catholic faith teaches that the devil’s ultimate defeat is already accomplished in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, as the Catechism affirms (CCC 550). The devil continues to operate not because God cannot stop him but because God, in his wisdom, has chosen to allow created freedom to play out within the limits he has set. This is not an excuse; it is a coherent theological position with a long history of careful development.

The Holy Trinity: Not a Logical Contradiction

One of the most commonly raised objections in the Reddit post is the question of how one God can exist as three Persons. The author clearly sees this as a logical impossibility, essentially a case of saying one equals three. Catholic theology has never claimed that one equals three, and the objection rests on a misreading of what the doctrine of the Trinity actually says. The Catechism states that the Trinity is one: we do not confess three Gods, but one God in three Persons, the consubstantial Trinity (CCC 253). The crucial distinction is between nature and Person. The three Persons of the Trinity, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, do not divide the one divine substance among themselves; each of them is wholly and entirely God, not one-third of God. Catholic theology draws on the philosophical distinction between what something is (its nature or substance) and who something is (its personal identity). Saying there are three Persons in one God is not saying three equals one; it is saying that the one divine nature subsists in three distinct personal relations. The Catechism further explains that the divine Persons are distinct from one another in their relations of origin, meaning that the Father is unbegotten, the Son is eternally begotten of the Father, and the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, while all three share the identical divine substance (CCC 254, 255). This is admittedly a mystery, meaning it goes beyond what human reason could arrive at on its own. But mystery and logical contradiction are not the same thing. A logical contradiction is a statement that is internally inconsistent. A mystery is a reality so deep that it exceeds human comprehension while remaining internally coherent. The Catechism explicitly calls the Trinity “the central mystery of Christian faith and life” and the “mystery of God himself” (CCC 234). Catholic theology does not pretend this is easy to understand; it simply maintains that the doctrine does not require one to believe that one equals three but rather that one divine nature is perfectly expressed in three distinct personal relationships.

Hell: Not an Arbitrary Punishment for Disbelief

Perhaps the most emotionally charged question in the post is why a loving God would send people to be tortured forever simply for not believing in him. Catholic teaching offers a very precise answer to this, and that answer differs in important ways from some popular presentations of hell. The Catechism does not describe hell as a punishment God imposes on people for intellectual disbelief. Instead, it describes hell as the permanent state of a person who, through their own free and final choice, has refused God’s love (CCC 1033). The Catechism is explicit: “God predestines no one to go to hell; for this, a willful turning away from God (a mortal sin) is necessary, and persistence in it until the end” (CCC 1037). This means hell is not a trap God sets for people who failed a knowledge test; it is the natural and permanent consequence of a free choice to close oneself off from the only source of true life and happiness. The Catechism also describes the chief punishment of hell not as fire or physical torment but as eternal separation from God, in whom alone man can possess the life and happiness for which he was created (CCC 1035). To put it simply, hell is what it looks like when a person gets exactly what they freely and finally chose: existence without God, forever. It is not God who is absent from the person in hell; it is the person who has made themselves permanently absent from God. Catholic theology is also careful to note that God “does not want any to perish, but all to come to repentance,” as 2 Peter 3:9 states. God actively wills the salvation of every person, and the Church’s teaching on hell is meant not as a threat but as a serious reminder of the weight of human freedom. The description of hell as simply “not believing” is a significant oversimplification of what Catholic theology actually teaches about mortal sin and final perseverance in evil.

The Role of Human Reason in Understanding God

One of the most important elements of Catholic teaching that the Reddit post overlooks is the Church’s deep commitment to reason as a valid tool for knowing God. Catholic theology does not ask people simply to switch off their intellect and accept things blindly. The First Vatican Council, a formal gathering of the Church’s leadership in the nineteenth century, explicitly taught that human reason can know God through the created world. The Catechism affirms this by listing several starting points for the natural knowledge of God, including the physical world, the human person, and the experience of truth and goodness (CCC 31-36). St. Thomas Aquinas developed his famous Five Ways, which are five philosophical arguments for God’s existence based on observation and reason alone, without appealing to Scripture. These arguments have been discussed, challenged, and defended by professional philosophers for over seven centuries, and they remain live topics in academic philosophy today. The Church therefore does not ask people to abandon reason; it asks people to apply reason carefully and to recognize that some realities, while not contrary to reason, go beyond what reason alone can fully grasp. The objections raised in the Reddit post, including the problem of evil, the nature of divine power, and the logic of the Trinity, have all been engaged by Catholic thinkers using philosophical tools as well as Scripture and tradition. The post treats these objections as if they have never been addressed or as if Catholic answers are merely emotional deflections. In fact, the history of Catholic intellectual life includes a vast body of serious philosophical and theological work on exactly these questions, from Augustine’s “Confessions” and “City of God” to Aquinas’ “Summa Theologica” to contemporary works in analytic philosophy of religion. Dismissing Catholic responses as equivalent to helicopter parents defending a spoiled child does not engage with the actual content of those responses.

What the Analogy of the Spoiled Child Gets Wrong

The Reddit post’s central analogy is both creative and worth examining closely, because it reveals the precise point where a misunderstanding of God leads to a misrepresentation of faith. The analogy of a spoiled child assumes that God is a being within the world who has been assigned tasks and who keeps failing to perform them, and that Christians are simply making excuses for those failures. This misses a fundamental point of Catholic theology, which is that God is not a being within the world in the way that a child, a president, or a mechanic is a being within the world. The Catechism describes God as the creator of heaven and earth, the one from whom all existence derives, the one who is not dependent on anything outside himself (CCC 295-301). God does not exist as one item among many in the universe who can be evaluated for performance against a set of externally defined criteria. To ask “why didn’t God stop that disaster?” in the same tone that one would ask “why didn’t the fire department respond in time?” is to assume that God occupies the same kind of position in reality as the fire department, which the Church firmly denies. The Catholic understanding of God’s relationship to the world is more analogous to the relationship between an author and a story than to the relationship between an employee and a job description. An author is not simply absent from their story when the characters suffer; the author is present to every moment of the story in a way no character within the story can fully comprehend. God’s manner of being present to his creation and governing it is not the same as a cosmic repairman who is expected to appear on demand. This does not mean God is indifferent; Catholic theology insists that God’s care is constant, personal, and complete (CCC 301-305). But it does mean that measuring God by human expectations of visible, on-demand performance reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of who God is.

Why Catholic Responses Are Not Excuses

The post specifically characterizes responses like “you simply don’t understand him” or “you shouldn’t expect God to meet your expectations” as hollow excuses. It is fair to acknowledge that these phrases, when stated without supporting reasoning, can feel dismissive and unhelpful. However, when they are backed by the full body of Catholic theological argument, they carry genuine intellectual content. The statement “you don’t fully understand him” is not a shut-down of conversation; it is a reference to a well-developed Catholic teaching about the limits of human knowledge when it comes to an infinite being. The Catechism teaches that God’s inner life infinitely exceeds all that we can imagine, and that the words we use to describe God, such as “almighty,” “knowing,” or “loving,” always fall short of the full reality (CCC 42-43). This theological principle, called negative theology or the via negativa, has been developed by major Catholic thinkers including Dionysius the Areopagite, Gregory of Nyssa, and Thomas Aquinas. It holds that all human language about God is analogical, meaning it applies to God truly but not in exactly the same way it applies to creatures. When Catholics say that God’s love is beyond our understanding, they are not saying that God gets a free pass to behave badly; they are saying that a being who is love itself cannot be adequately evaluated using the same categories we use for human behavior. The statement “you shouldn’t expect God to meet your expectations” is similarly not an excuse; it is a reflection of the consistent Catholic teaching that God’s purposes are ordered toward an eternal good that includes but goes beyond what happens in this life. This is why Catholic responses to suffering consistently point toward the resurrection, which is the definitive statement that God does not abandon his creatures to meaningless pain but transforms even death into something new.

God’s Silence and the Meaning of Faith

The post’s demand that God “stop hiding” reflects an experience that the Catholic tradition takes seriously and does not dismiss. Many of the greatest figures in Catholic history, including St. John of the Cross and Mother Teresa of Calcutta, wrote about periods of intense spiritual darkness in which God seemed entirely absent. St. John of the Cross described this experience as the “dark night of the soul,” a period in which all sensible consolation in faith disappears and the person feels utterly alone. Mother Teresa’s private correspondence revealed that she experienced decades of this kind of silence, even while continuing her remarkable work for the poor. The Church does not present God’s silence as evidence of his absence or indifference; it presents it as a feature of the spiritual life that many believers will experience, and as something that can itself be a form of growth and deeper trust. The Catechism acknowledges this when it speaks of God’s apparent powerlessness in the face of evil as itself a form of revelation (CCC 272). This is not a comfortable answer, and the Church does not present it as one. But it is an honest engagement with the reality that God does not always feel close or obvious, even to those who love him most. The post treats the silence of God as a knock-down argument against his existence or care. Catholic theology treats it as a genuine and difficult aspect of faith that believers must honestly confront, not a problem that can be resolved by simply demanding that God make himself more visible. The nature of love, both human and divine, includes a willingness to be with someone in their absence and uncertainty, not just in their presence and certainty. A faith that required constant visible proof would not be faith at all; it would simply be sight, which is a different thing entirely.

What Psalm 115 Actually Says and Why the Post Misuses It

The decision to close the Reddit post with Psalm 115:4-8 is interesting, because the author clearly intends it as a charge against the God of Christianity, suggesting that this God is as silent and lifeless as the idols the psalm describes. But this reading requires a fundamental misunderstanding of what the psalm is actually doing. The psalm draws a sharp and explicit contrast between the living God of Israel, who does whatever he pleases in heaven and on earth (Psalm 115:3), and the lifeless idols made of silver and gold by human hands. The psalmist’s point is precisely that the God of Israel is not like these objects; he is the God who acts, who speaks, who delivers, who blesses (Psalm 115:12-18). The idol critique in the psalm is a critique of gods who truly cannot see, hear, or act, because they are manufactured objects without consciousness or power. The God of Catholic faith is not described as silent, helpless, or made of human hands. He is described as a personal, acting, self-revealing God who spoke to Abraham, who led Israel out of Egypt, who became incarnate in Jesus Christ, and who sent the Holy Spirit to the Church. To use a psalm that was written to exalt the living God over dead idols as a weapon against that same living God is to use the text against its own explicit purpose. St. Augustine, one of the greatest Catholic thinkers, wrote an extensive commentary on Psalm 115 in which he read it as a call to reject all forms of false trust and to place confidence entirely in the living God who acts in history. Catholic teaching on idolatry, furthermore, explicitly forbids the worship of any object as if it were God (CCC 2112-2114), so the Church would fully agree with the psalm’s condemnation of lifeless idol worship; what it denies is that the God revealed in Jesus Christ is in any way comparable to those idols.

The Consistency of Catholic Doctrine Over Time

One of the implicit suggestions in the Reddit post is that Catholic defenses of God are improvised and post-hoc, made up on the spot whenever a challenge arises. This is historically and factually inaccurate. The questions the post raises, about evil, about divine power, about the Trinity, and about eternal consequences, have been central topics in Catholic theology from the earliest centuries of the Church. Justin Martyr, writing in the second century, engaged with pagan criticisms of Christian belief. Origen of Alexandria, in the third century, wrote systematic responses to the Greek philosopher Celsus who argued that Christianity was intellectually incoherent. Augustine, in the fifth century, devoted major works to exactly the questions the post raises, including the problem of evil in “The City of God” and the nature of the Trinity in “De Trinitate.” Thomas Aquinas, in the thirteenth century, organized the entire body of Catholic theology into a systematic form in his “Summa Theologica,” specifically including careful arguments about divine power, the nature of evil, and the logic of eternal life. The Second Vatican Council, in the twentieth century, addressed the relationship between faith and reason, affirming that the two are not opposed but complementary (a teaching reflected in Pope John Paul II’s encyclical “Fides et Ratio” from 1998). The consistency of this tradition over nearly two thousand years is itself an argument against the idea that Catholic responses are mere evasions. A tradition of honest intellectual engagement with hard questions, maintained across diverse cultures, centuries, and intellectual climates, does not look like the behavior of helicopter parents covering for a spoiled child; it looks like a community that takes both God and human reason seriously.

The Question of God’s Justice and Loving Nature Together

One of the tensions the post highlights, though not always explicitly, is the apparent conflict between God’s love and his justice. If God is truly loving, how can he allow anyone to face eternal consequences? If God is truly just, how can he forgive sins at all? Catholic theology addresses this tension not by choosing one attribute over the other but by showing how they are united in God’s nature. The Catechism teaches that God’s mercy and his justice are not in competition; rather, God’s mercy is itself a form of justice that goes beyond what strict legal accounting would require (CCC 270, 277). The entire Catholic understanding of the Incarnation, that God himself became human in the person of Jesus Christ, is precisely the answer to this tension. God did not simply wave away human sin as if it had no real weight; he entered into human suffering himself, took the consequences of sin upon himself in the crucifixion, and overcame those consequences in the resurrection. This is described in Catholic teaching as the most complete act of both justice and mercy: justice, because the real weight of sin was acknowledged and dealt with, and mercy, because it was God himself who bore that weight on behalf of his creatures. The offer of salvation, which the Church teaches is extended to all people through means that may go beyond formal membership in the Church (CCC 847), means that no one arrives at a final state of separation from God without having been offered the possibility of turning back. The Catholic teaching on salvation and on hell is therefore not a picture of a God who arbitrarily punishes people for failing a theological exam; it is a picture of a God who offers himself completely and who respects the final freedom of creatures to accept or refuse that offer.

Addressing the Tone of Debates About God

The Catholic faith does not ask its members to be offended by hard questions about God. The tradition of apologetics, which means the reasoned defense of faith, has always included Catholics who welcome intellectual challenge and engage it honestly. The post’s frustration is real and should be respected; many people have left Christianity after experiences of unanswered prayer, witnessed suffering, or encounters with Christians who responded to honest questions with defensiveness rather than reason. The Church itself acknowledges that the way Christians communicate their faith matters enormously, and that arrogance, dismissiveness, or intellectual laziness in responding to challenges does real harm. Pope Francis, in his apostolic exhortation “Evangelii Gaudium,” wrote that the Church must go out to meet people where they are and engage their real questions with honesty and humility. The comparison between Christian apologetics and helicopter parenting is colorful, but it fails to account for the vast body of serious, honest, self-critical Catholic theological work that engages these exact questions without defensiveness. The real question the post raises is not whether God can be questioned; Catholic theology invites that. The real question is whether the objections raised in the post, valid and heartfelt as they are, actually succeed as arguments against the coherent Catholic understanding of God. On careful examination, the answers given above show that they do not, not because God gets a special pass, but because the objections rest on a version of God that Catholic theology does not hold.

Why Free Will Is Central to Everything

Almost every question raised in the Reddit post, whether about disaster prevention, the devil’s existence, or eternal consequences, connects back to one central reality in Catholic theology: the dignity and reality of human and angelic free will. The Catechism states that freedom is the power, rooted in reason and will, to act or not to act, and that by free will one shapes one’s own life (CCC 1731). God created free beings not because it was the easiest option but because genuine love and genuine goodness can only exist where genuine freedom is real. A God who prevented every bad outcome by controlling every choice would not be the creator of free beings; he would be the creator of sophisticated machines. The Catholic tradition insists that the world God made, including its risks and its suffering, is better than a world of beings incapable of genuine love, genuine choice, and genuine relationship with God. This does not mean suffering is good in itself; it means that the conditions that make suffering possible are the same conditions that make love, courage, compassion, and self-sacrifice possible. The Catechism quotes the ancient liturgy in a phrase that has puzzled many: “O happy fault, O necessary sin of Adam, which gained for us so great a Redeemer.” This is not a celebration of evil but a recognition that God’s response to human freedom, even when that freedom is used catastrophically, reveals a depth of love and creative power that would not have been visible otherwise. Free will, in Catholic thought, is not a problem to be solved; it is a gift to be honored, and honoring it means allowing its consequences to be real.

The Living God Versus the God of Caricature

Throughout its engagement with questions like those in the Reddit post, Catholic theology consistently draws a distinction between the God it actually believes in and the God that critics are often attacking. The God the post describes, one who hides, who fails to stop disasters, who needs to be defended by his followers, and who threatens people with eternal fire for minor infractions of belief, is a caricature rather than an accurate presentation of Catholic faith. The God of Catholic teaching is described as one who is closer to each person than that person is to themselves, a phrase from Augustine that the Catechism echoes in its treatment of divine providence (CCC 300). The God of Catholic faith is one who entered human history in the flesh, who wept at a grave (John 11:35), who healed the sick, who ate with people the religious establishment rejected, and who died a violent death out of love for the very people who rejected him. This God is not hiding in any trivial sense; he has made himself known through the most striking possible means, the Incarnation, and continues to make himself present through the Eucharist, through Scripture, and through the community of believers. The challenge is not that God is absent; the challenge is that his presence does not take the form of constant visible intervention that removes all difficulty and uncertainty. Catholic faith holds that a God who acted that way would, paradoxically, be less present to his creatures than the God who respects their freedom and walks with them through suffering rather than simply eliminating it.

How Catholics Respond to Doubt Honestly

It is worth closing by acknowledging that the Catholic tradition makes real room for doubt, questioning, and honest uncertainty. The faith does not require that believers pretend to have all the answers or that they suppress legitimate intellectual questions. The Catechism speaks of faith as including a genuine engagement of the whole person, intellect, will, and affection, in a free response to God’s self-revelation (CCC 143-144). This means that a person who genuinely wrestles with the questions raised in the Reddit post is, from a Catholic perspective, engaged in something more honest and more valuable than a person who simply accepts everything without reflection. The tradition of “faith seeking understanding,” articulated most clearly by Anselm of Canterbury in the eleventh century, holds that faith and understanding are not enemies but companions. Believers are expected to bring their most honest questions to their faith, to examine them carefully, and to grow through that process. The Church does not promise that every question will receive a fully satisfying answer in this life. It does promise that every question is worth asking, that God is not threatened by honest inquiry, and that the resources of the Catholic intellectual tradition are rich enough to engage even the hardest objections. The Reddit post, for all its sharp edges, is asking questions that honest believers also ask, and the Catholic faith is not afraid of them. The answers given in this article do not claim to remove all difficulty or to make faith effortless; they simply show that the objections raised do not succeed in dismantling the Catholic understanding of God and that there are serious, well-developed reasons for maintaining that faith is both reasonable and true.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.