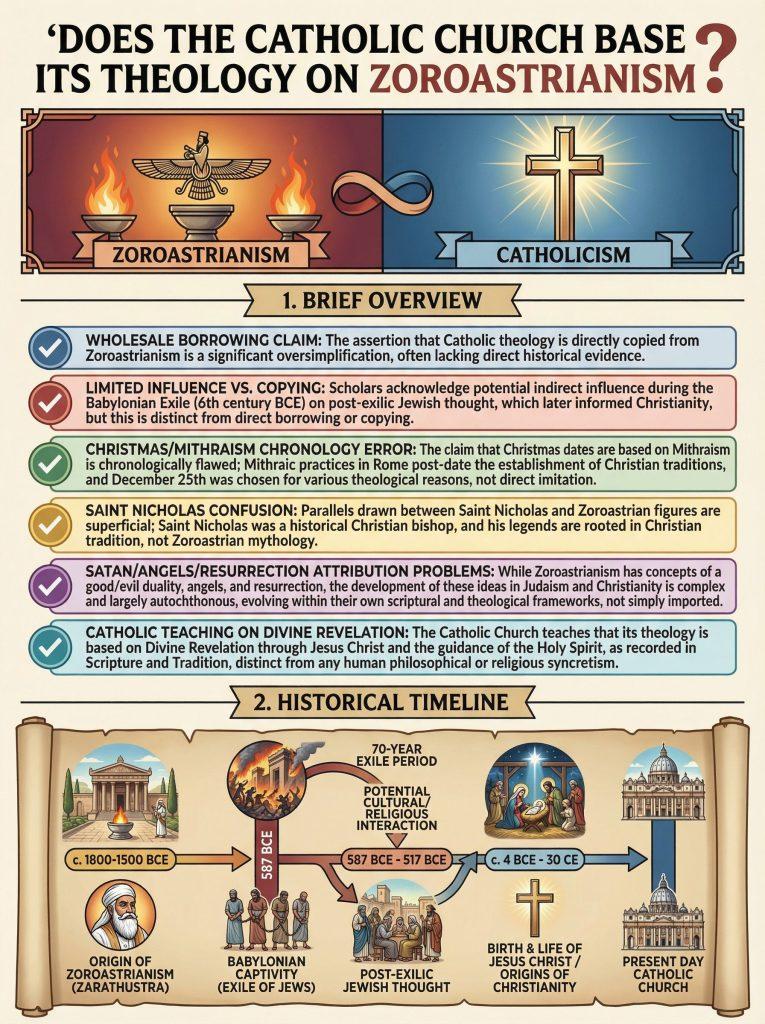

Brief Overview

- The claim that Catholicism represents wholesale borrowing from Zoroastrianism oversimplifies complex historical relationships and misrepresents how Christian doctrine actually developed.

- While some scholars acknowledge limited influence from Zoroastrianism on Jewish thought during and after the Babylonian Captivity, this does not establish that the Church simply copied foreign religious concepts.

- The notion that Christmas was adopted from Mithraism in the fifth century contradicts historical evidence, as December 25 was already established as a Christian celebration by the fourth century.

- Claims connecting Saint Nicholas to Zoroastrian priests lack scholarly support and confuse distinct historical figures with separate origins and purposes.

- The attribution of theological concepts such as Satan, angels, and resurrection entirely to Zoroastrian sources ignores the internal religious development within Judaism and the continuity of scriptural theology.

- Catholic teaching maintains that truth revealed through Scripture and Tradition comes from divine revelation rather than from borrowed pagan mythology or cultural sources.

Understanding the Zoroastrianism Claim in Historical Context

The assertion that the Catholic Church built its entire theological framework on concepts borrowed from Zoroastrianism represents one of the most sweeping historical claims made against Christian doctrine. This accusation often presents itself as conclusively settled fact when scholars actually remain deeply divided on the extent and nature of any Zoroastrian influence on Judaism and Christianity. Some scholars do acknowledge that Zoroastrian eschatological concepts may have influenced certain Jewish thought following the Babylonian Captivity, but this is vastly different from claiming that core Christian theology is essentially Zoroastrian repackaging. The historical record is more complicated than simple borrowing would suggest, involving multiple layers of cultural contact, internal theological development, and genuine revelation. Catholics approach these claims with the conviction that divine revelation transcends cultural contexts while remaining intelligible within them. Understanding the specifics of each alleged connection requires careful attention to chronology, textual evidence, and scholarly consensus rather than accepting sweeping generalizations as historical truth. The foundation of the plagiarism claim often begins with the observation that Zoroastrianism is chronologically older than Christianity and was widespread throughout the ancient Near East and Mediterranean world. It is true that Zoroastrianism, originating sometime between 1800 and 1500 BCE, had significant influence throughout regions where Jewish and Christian communities developed. However, chronological priority does not automatically establish causal influence, especially when intermediate sources and internal development within a tradition can account for similar concepts. The Jewish people had extensive contact with Persian culture during and after the Babylonian Captivity, beginning in 587 BCE when the Temple was destroyed and the Jewish people were exiled to Babylon, and this period of contact lasted for seventy years.

Many scholars note that certain Jewish theological developments, particularly in areas concerning the end times and spiritual beings, may have been influenced by Persian thought during this period. However, Jewish tradition itself attributes the development of these doctrines to divine revelation and scriptural interpretation rather than foreign borrowing. The Church teaches that God reveals himself progressively throughout history, addressing people in their particular cultural and linguistic circumstances. This does not mean that all revelation comes from outside sources or that similarities between religions indicate borrowing in one direction. Rather, God’s word became incarnate in human history and human culture, addressing people where they were while maintaining the absolute transcendence and uniqueness of divine truth. The Catholic position recognizes that while God spoke through the prophets of Israel and later through Christ, this does not require that all similar concepts in other religions derive from Christian sources or that Christianity derives concepts from other religions. Instead, the Church maintains that its doctrines flow from God’s self-revelation in Christ, from Scripture, and from the consistent teaching of the Church throughout the centuries. This understanding allows the Church to acknowledge linguistic connections, historical contacts, and even some possible cultural influences while maintaining that Christian doctrine ultimately rests on a divine foundation rather than on human borrowing.

The Role of Textual Dating and Biblical Chronology

A critical element often overlooked in the plagiarism argument concerns the dating and authorship of biblical texts and how this affects claims about borrowing from Zoroastrianism. Traditional Jewish and Christian teaching, supported by significant scholarly evidence, credits Moses with writing the Torah during a period estimated at 1400 to 1200 BCE. If this chronology is accepted, then many foundational theological concepts appeared in Jewish scripture centuries before Zoroastrianism could have influenced them, since the Babylonian Captivity did not occur until 587 BCE. Modern scholars typically place the composition of the Torah at a much later date, generally between 900 and 400 BCE, which would allow for greater possible influence from surrounding cultures during and after the Babylonian Captivity. Yet even scholars who adopt this later dating acknowledge that many narratives preserved in these texts preserve memories of much more ancient events and traditions. The Ignatius Catholic Study Bible notes that “the vast stretch of Jewish and Christian tradition credits the Pentateuch to Mosaic authorship” and that “studies of the Book of Genesis within its Near Eastern context tend to confirm both the antiquity and the authenticity of its traditions.” This means that the timing and direction of possible influence remains genuinely contested among scholars and cannot be used as a basis for definitive claims about Christian doctrine being borrowed from Zoroastrianism.

Furthermore, the presence of similar concepts across ancient religions does not necessarily indicate borrowing in one direction or the other. In the ancient world, multiple cultures developed comparable responses to universal human experiences and questions that every civilization must address. Zoroastrianism and Judaism both grappled with the problem of evil, the nature of the divine, and the ultimate destiny of humanity and the cosmos. These are not trivial matters with obvious answers, and it should not surprise us that different religious traditions arrived at similar conclusions through their own reflection, revelation, and theological development. The Catholic understanding of divine revelation, as expressed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, suggests that God communicates truth through multiple means and to multiple peoples according to their capacity and circumstances. This does not require that all true ideas come from a single source or that traditions cannot arrive at similar conclusions independently. When examining specific theological claims, it becomes necessary to look beyond sweeping generalizations and consider the actual evidence for each alleged borrowing. For each major doctrine claimed to derive from Zoroastrianism, the Church can trace the concept through Scripture and the continuous teaching of the Church throughout history. If a doctrine appeared suddenly in one period without precedent in Scripture or earlier Church teaching, that would indeed raise questions about its authenticity and source. However, the major doctrines claimed to be borrowed from Zoroastrianism fail to match this pattern.

The Etymology of Paradise and Its Theological Meaning

One of the more straightforward claims made against Catholic theology concerns the word “paradise” and its supposed Persian origins, which critics use to suggest the entire doctrine of paradise is borrowed from Zoroastrianism. This claim is partially correct but requires careful qualification to understand properly. The word “paradise” does indeed derive from Old Persian origins, specifically from the Persian term “pairidaeza,” which meant an enclosed garden or walled park. This etymological fact is readily acknowledged by Catholic scholars and biblical commentators without embarrassment or defensive claims. The Catholic Answers Encyclopedia explicitly states that “the word paradise is probably of Persian origin and signified originally a royal park or pleasure ground.” This demonstrates that Catholic scholarship does not hide linguistic origins but rather discusses them openly and accurately. However, the existence of a Persian etymological origin for a word used in theology does not establish that the theological concept itself is borrowed from Zoroastrianism or that the Christian understanding of paradise derives from Persian religion.

The path of this word through various languages illustrates how words can travel across cultures while maintaining distinct meanings in each tradition where they are adopted and used. The Persian term entered Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek as these languages encountered Persian administrative and cultural contexts through trade, political contact, and military campaigns. It appeared in the Hebrew scriptures in books such as Nehemiah, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs, where it retained its original meaning of an enclosed garden or park used for cultivation and recreation. When the Greek Septuagint was translated, it rendered the Hebrew term with the Greek equivalent “paradeisos,” maintaining the same basic physical and descriptive meaning. As Christianity developed and the Church engaged with Greek culture and adopted Greek as a primary language for theological discourse, it incorporated this term into theological language to describe the heavenly reward promised to the faithful. The Jewish and Christian understanding of paradise, however, developed from Scripture and theological reflection on divine promises rather than from Persian religious doctrine about paradise as a spiritual reward. That the Church borrowed a convenient and descriptive word from Persian to express Christian theological concepts represents cultural and linguistic exchange, which is entirely different from theological plagiarism from pagan sources. Many words in Christian theology come from Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and other languages. Using these words in Christian theological contexts does not mean the doctrines themselves are borrowed from the cultures that originated the words.

Satan and Angels in Scripture and Christian Doctrine

The claim that Satan, angels, and the Holy Spirit were borrowed entirely from Zoroastrianism requires careful examination of biblical sources and Church teaching. The Catholic Church’s teaching on Satan and angels developed from Scripture and the Church’s ongoing theological reflection guided by the Holy Spirit, not from cultural borrowing. Catholic doctrine affirms the existence of angels as spiritual beings created by God to serve His purposes and worship Him in the heavenly court. The teaching that Satan is a fallen angel who rebelled against God appears clearly in Scripture, particularly in texts such as 2 Peter 2:4, Revelation 12:7-9, and Jude 1:6. These texts describe celestial conflict and the rebellion of angelic beings led by a figure opposed to God. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches at paragraph 391 that Satan is a fallen angel, and at paragraphs 391-395 the Church presents Satan’s fall in relation to God’s creation of all beings good. The Church teaches that these fallen angels, led by Satan, were originally created good but chose through pride to turn away from God. The Fourth Lateran Council explicitly defined against the Albigenses that “the devil and the other demons were created by God good according to their nature, but they became evil by their own doing.” This doctrine reflects centuries of theological reflection on Scripture rather than simple borrowing from Zoroastrian concepts.

The presence of similar concepts across religious traditions does not establish that one borrowed from another without rigorous historical documentation. Zoroastrianism does teach about evil forces opposing the good god Ahura Mazda, and it does include concepts of spiritual warfare and divine struggle. However, the specific Christian understanding of Satan as a created being who rebels through pride, the role of Satan in tempting humans to sin and leading them away from God, and the ultimate victory of Christ over Satan represent distinctly Christian theological developments. These concepts emerge from the narrative of Scripture beginning with Genesis, where the serpent tempts the first humans to disobey God and eat from the tree of knowledge, and continuing through the Gospels, where Christ encounters Satan in the wilderness and defeats him through His death and resurrection. The meaning and purpose of Satan in Christian theology differs significantly from the role of evil forces in Zoroastrianism when examined carefully. Catholic teaching understands Satan as a creature whose evil has already been overcome by Christ’s redemptive work through the Cross, even though Satan continues to tempt humans until the end of time. This theological understanding developed gradually within the Christian community through prayerful reflection on Scripture and experience of spiritual reality. The Church’s teachings on angels and Satan appear consistently throughout the patristic period and through medieval theology. The consistent testimony of Church Fathers from the earliest centuries affirms these doctrines based on scriptural interpretation rather than adopting them suddenly from Persian sources.

Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment

Among the most significant claims is that the doctrine of bodily resurrection and the Last Judgment were borrowed wholesale from Zoroastrianism. The scholar Bart Ehrman, in his scholarly blog on historical questions concerning Christianity, notes that “it is unified in saying that the Jewish doctrine of resurrection was not found in Greek and Roman circles outside of Judaism and Christianity.” This statement is important because it suggests that resurrection doctrine developed within the Jewish tradition as a distinct contribution to religious thought rather than something shared across Mediterranean cultures where Judaism and Christianity would encounter other religions. While Zoroastrianism does teach about a final judgment and resurrection of the dead, the Jewish and Christian doctrines of resurrection have their own internal development within the Jewish scriptural tradition. The Jewish understanding of resurrection grew from reflection on God’s covenant with Israel and the promise that God who gave life would restore life even after death. The teaching on resurrection in Jewish thought developed gradually, and scholars trace this development through various biblical books and intertestamental writings.

Early Jewish texts and the Hebrew scriptures contain references to resurrection that suggest internal development rather than straightforward foreign borrowing. The book of Daniel, traditionally dated to the second century BCE, contains the clearest early Jewish statement of resurrection doctrine in biblical texts, particularly in Daniel 12:2. Other Jewish texts from the intertestamental period, such as the Maccabees and various apocalyptic writings, further develop the concept of bodily resurrection as part of God’s ultimate restoration of creation and vindication of the righteous. While scholars debate the possible influence of Zoroastrian thought on later Jewish eschatology, these same scholars also recognize that internal factors within Judaism contributed significantly to the development of resurrection doctrine. Many Jewish communities, particularly the Pharisees, embraced resurrection belief as central to their understanding of God’s justice and fidelity to the covenant. The Catholic Church affirms the doctrine of bodily resurrection as essential to Christian faith, as expressed in the Nicene Creed and the teaching of Scripture. This doctrine appears prominently in 1 Corinthians 15, where Saint Paul explains the reality and nature of Christ’s resurrection as the foundation for Christian hope in resurrection for all believers. Catholic theology teaches that the Last Judgment follows the general resurrection of the dead, when Christ will judge all humans according to their deeds and each person’s eternal destiny will be determined. These doctrines developed within the Christian community through careful meditation on Scripture and the revelation of Christ’s own resurrection as the foundation for hope in eternal life and God’s ultimate plan.

Christmas and the December 25 Date

Perhaps no claim made against Catholic practice is more popular in certain circles than the assertion that Christmas was adopted from the Mithras cult and that this occurred in the fifth century as part of the Church’s supposed appropriation of pagan practices. This claim contains multiple factual errors that can be readily documented through historical sources. The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that Christians were already celebrating the birth of Christ on December 25 by the fourth century, not the fifth century. The earliest recorded official celebration of Christmas on December 25 occurred in Rome in 336 CE during the reign of Constantine. Some scholars argue that Christmas celebrations on this date may date even earlier, possibly to the second century, though this remains disputed among academic historians. The significant point is that the fifth century date mentioned in the original claim is historically inaccurate by at least one hundred years, making the basic chronology of the claim simply false. This chronological error undermines the entire argument about Christmas being adopted from Mithraism in the fifth century.

The dating of Christmas to December 25 likely involved multiple historical and theological considerations rather than simple adoption of pagan practice. Some scholars suggest that early Christians chose December 25 because of theological calculations about Jesus’s conception at the spring equinox, which would place birth approximately nine months later near the winter solstice and thus December 25. Others note possible connections to Jewish holy days or the numbering systems in early Church documents. What is clear from the historical record is that no Christian source from this period explicitly states that the date was chosen to coincide with Mithraic festivals or to replace pagan observances. The cult of Mithras, which did celebrate a festival connected to the winter season according to some sources, was actually declining in influence by the time the Church formally established Christmas in the fourth century. In 274 CE, the Roman emperor Aurelian established a festival honoring Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun, on December 25, which some scholars suggest may have influenced Christian choice of date. However, this represents a different pagan festival than Mithraism, and by the fourth century when the Church formally established Christmas, the Mithraic cult was losing adherents rather than gaining influence in the Roman Empire. The Church did not invent Christmas as a pagan replacement but rather developed it as a genuine Christian observance with its own theological significance.

Early Church and the Development of Christmas Observance

It is true that the early Church did not celebrate Christmas in its first three centuries of existence, which some critics point to as evidence that the doctrine was later invented or borrowed. The earliest Christian communities focused their liturgical observance primarily on Easter, commemorating Christ’s death and resurrection, which they understood as the central mystery of salvation and the foundation of Christian faith. This early silence on Christmas does not, however, support the plagiarism argument as critics claim. Rather, it simply reflects the fact that the Church’s liturgical calendar developed gradually as the faith spread and became established throughout the Roman Empire. By the time Christmas began to be celebrated and formally established, usually attributed to the fourth century under Constantine, Christianity had become the dominant religion of the empire. The establishment of Christmas celebration at this time represents not plagiarism from pagan sources but rather the Church’s decision to set aside a specific feast day to honor Christ’s nativity with proper solemnity. This decision came from within the Church’s own theological development and pastoral practice, not from pressure to adopt pagan customs or replace pagan festivals.

The Church’s practice of choosing significant dates and seasons to focus on particular mysteries of faith reflects the principle that God’s revelation is recalled and celebrated within time according to the pattern of the Church’s liturgical life. Just as the Church developed feast days for Saints and other Christian mysteries, so too did it develop a feast for the Nativity of Jesus. The development of Christmas as a liturgical celebration demonstrates the living Church’s approach to expressing faith through the calendar and the seasons of time. The fact that the date coincided with the winter solstice and possibly with pagan celebrations does not establish that the Church borrowed the doctrine of the Incarnation from paganism. Rather, the Church intentionally chose a date and sanctified it through Christian meaning and celebration. This represents the normal process by which the Church takes cultural moments and transforms them through Christian theological significance. The establishment of Christmas did not require borrowing the concept of Christ’s birth from any pagan religion. The Gospels themselves, written in the first century, clearly attest to Christ’s birth and provide the foundation for Christian celebration of this mystery. The development of the Christmas celebration represents the Church’s deepening engagement with the mystery of the Incarnation, not the adoption of foreign pagan mythology into Christian practice.

Saint Nicholas and the Three Kings as Distinct Figures

The claim that Saint Nicholas is somehow a distortion of Zoroastrian priests and that the Three Kings represent a political manipulation by the Church requires careful historical clarification. Saint Nicholas was a historical figure who lived in the fourth century in Myra in what is now Turkey and is well documented in historical sources. He was a Christian bishop known for his generosity, pastoral care, and the miraculous works attributed to him through tradition and the testimony of the faithful. Tradition holds that Nicholas was born into a wealthy Christian family and used his inheritance to help the poor and suffering in his community. He became venerated as a saint and his legend grew throughout medieval Christendom, eventually giving rise to traditions about gift-giving and charitable acts in his name. However, there is no historical connection between Saint Nicholas and Zoroastrian priests, and no scholarly evidence whatsoever supports the claim that his figure was deliberately created to replace Zoroastrian religion. Saint Nicholas is known for giving gifts, but these gifts were sacks of gold given to three impoverished sisters to preserve their honor and allow them to marry respectably, not gifts given to a god-child as the Magi brought to Jesus in the Gospel narrative.

The Three Kings or Three Wise Men, known in tradition as Balthasar, Melchior, and Caspar, were the Magi who visited Jesus after his birth according to the Gospel of Matthew, which is the only Gospel to mention them. These Magi are described in Scripture as coming from the east, attracted by a star and bringing gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to honor the newborn king. Many scholars believe these Magi were likely Zoroastrian priests or practitioners of a similar Persian religion, as the term “magus” derives from the Median priestly class that practiced and preserved Zoroastrianism. However, the Church did not create the Magi narrative as a political manipulation to incorporate Zoroastrian figures into Christian teaching. Rather, the Gospel of Matthew explicitly includes the Magi in the infancy narrative, and the Church’s tradition developed names and identities for these figures over centuries as the story was retold and reflected upon in liturgy and theology. The inclusion of the Magi in the nativity story actually demonstrates the Church’s openness to recognizing the truth and wisdom in cultures outside Israel. As one Catholic commentary explains, the Magi represent that the light of Christ is given not only to the Jewish people but also to the Gentiles and to those outside the covenant community who seek truth and are open to God’s revelation. This theological meaning, developed by the Church over centuries, reflects the universal scope of Christ’s redemption and God’s plan to save all humanity rather than representing political manipulation for religious purposes.

Understanding Influence Without Accepting Plagiarism

To acknowledge that Zoroastrianism may have influenced certain developments in Jewish thought is not the same as claiming that Christianity is simply Zoroastrianism in new form or that Catholic doctrine represents plagiarism from pagan sources. Even scholars who acknowledge some Zoroastrian influence on Jewish eschatology and angelology recognize that Judaism developed its own distinctive theology within the context of Israel’s covenant relationship with God. The Jewish understanding of God’s character, covenant, law, and promise forms the foundation of Christian theology and faith, not any external religious system or borrowed pagan concepts. Judaism contributed to Christianity the understanding of God as radically monotheistic, personally involved in human history, and committed to justice and mercy. These core convictions shaped Christian faith from its beginning and distinguish Christian teaching from other religious traditions. Christianity added to this biblical foundation the proclamation that Jesus is the Messiah, Son of God, whose death and resurrection accomplished salvation for all humanity. This theological development emerged from the experience of the resurrection and the Church’s meditation on Scripture in light of that transformative event. The Church’s approach to truth is not exclusive or defensive but rather recognizes that God has not left himself without witness anywhere in creation.

The Second Vatican Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate acknowledged that the Church respects whatever is true and holy in other religions and recognizes the seeds of the Word scattered throughout human cultures. This does not mean that all religions are equally true or that the Church has simply borrowed foreign concepts wholesale without distinction. Rather, it means that truth belongs to God and the Church recognizes God’s truth wherever it appears while maintaining the conviction that God’s full revelation comes through Christ and His Church. A word like “paradise” can have Persian origins through normal linguistic borrowing and still carry Christian meaning shaped by Scripture and theological reflection. A concept like resurrection can appear in multiple religious traditions and still have its own distinctive meaning and development within each tradition based on internal theological development. Borrowing a useful term or developing similar answers to universal questions differs fundamentally from the wholesale plagiarism claimed in the original argument against Catholic doctrine. The Church does not attempt to hide linguistic origins or pretend that cultural contact did not occur between Judaism and surrounding religions. Instead, the Church maintains that while borrowing of words and possible influence on thought patterns may have occurred, the substance of Christian doctrine derives from God’s revelation in Christ, from Scripture, and from the Church’s consistent teaching throughout the ages.

The Catholic Understanding of Divine Revelation

The Catholic Church understands divine revelation as God’s self-communication to humanity through deeds and words intrinsically bound together in a unified purpose. This revelation occurred progressively throughout history and throughout the world in various ways, reaching its fullness and completion in Jesus Christ, God’s Son and the Savior of humanity. The Church teaches that revelation is contained in Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition, both of which must be interpreted by the living Magisterium of the Church with its authentic teaching authority. This understanding of revelation shapes Catholic responses to claims of borrowing and plagiarism from other religions. If Catholic doctrine is authentic revelation from God, then it cannot be properly understood as plagiarism from human sources, even if some concepts or terms may be similar to those found in other traditions. The Church does not claim that God’s revelation occurred in a cultural vacuum untouched by human context and history. Rather, God’s revelation became incarnate in human culture and history, addressing people in their particular circumstances and using concepts and categories familiar to them.

The development of Christian doctrine represents the Church’s deepening understanding of revealed truth under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, not the gradual accumulation of borrowed ideas from external sources. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches at paragraphs 94-100 that the understanding of faith grows through the prayers, study, and holiness of the faithful, through the spiritual experience of the saints, and through the teaching authority of the bishops united with the Pope. This growth in understanding involves studying revelation’s connection to the broader context of human knowledge and culture, but it maintains that the source of Christian doctrine is God’s revelation in Christ, not external human sources. When examining specific doctrines, the Church looks back to Scripture as the foundational witness to God’s revelation and to the consistent teaching of the Church throughout history as the safe guide to correct interpretation. The Catechism explains at paragraphs 74-95 that Scripture is the speech of God put down in writing and that the Church is the living body that preserves and transmits the faith. If a doctrine appeared suddenly in one period without precedent in Scripture or earlier Church teaching, that would indeed suggest external influence rather than genuine development of revealed truth. However, the major doctrines claimed to be borrowed from Zoroastrianism can be traced through Scripture and early Church teaching to authentic Christian sources.

Scripture as the Foundation of Christian Doctrine

Every significant doctrine claimed to derive from Zoroastrianism has deep roots in Scripture that demonstrate its Christian origin and connection to revelation. The doctrine of Satan as a fallen angel comes directly from biblical texts that predate any alleged Zoroastrian influence on Judaism. The book of Isaiah, traditionally dated to the eighth century BCE and thus predating the Babylonian Captivity, contains imagery of rebellion in heaven and the fall of a proud angelic being. This passage is interpreted in Christian tradition as referring to Satan’s rebellion and fall from grace. The book of Revelation, written in the first century CE by early Christians, explicitly describes war in heaven with Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon, identified clearly as Satan and his forces. If Christians borrowed this doctrine from Zoroastrianism, it would be remarkable that earlier Jewish texts independently developed the same concept before the supposed contact occurred in the Babylonian Captivity centuries later. The doctrine of resurrection similarly appears in Jewish texts that scholars trace to internal Jewish theological development responding to crises and persecution. The Maccabees, who suffered persecution under the Greek Seleucid dynasty in the second century BCE, saw in the deaths of faithful Jews a reason to believe that God would raise them up to reward their faithfulness and vindicate their suffering.

Angels in Christian theology play roles shaped by biblical narrative and theological interpretation of Scripture throughout the Old and New Testaments. The Old Testament describes angels as God’s messengers and servants, beings who worship God and carry out God’s purposes in human history. The New Testament continues this understanding and adds details about angelic hierarchies and their role in salvation history. The Holy Spirit appears throughout the Hebrew scriptures as God’s active presence and power in the world, not as a borrowed concept from Zoroastrianism but as part of the internal development of Jewish monotheism and understanding of God. God’s three-fold nature as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, revealed in the incarnation of the Word and the sending of the Spirit, emerged from Christian experience and reflection on Scripture, gradually developing into the doctrine of the Trinity over the first few centuries of Christian theology. Each of these doctrines can be traced through layers of development within Scripture itself, from earlier to later books, showing how the Church’s understanding deepened through prayerful engagement with God’s word. If these doctrines were simply borrowed from Zoroastrianism wholesale, one would expect to find them appearing suddenly in Christian sources fully formed without previous development. Instead, the actual historical record shows gradual theological development, with some concepts appearing embryonically in earliest Christianity and becoming more clearly articulated over time as the Church sought to understand and communicate revealed truth accurately.

Scholarly Consensus and Genuine Academic Disagreement

Scholars who study the relationship between Zoroastrianism and Christianity remain divided on the extent and nature of any influence one religion may have had on the other. As one scholarly source notes, “Scholars remain divided on the extent of Zoroastrian influence on Judaism, with some arguing for significant direct borrowing of ideas, while others suggest these developments were also influenced by internal evolution within Judaism and other cultural exchanges.” This honest acknowledgment of scholarly disagreement contrasts sharply with claims that Zoroastrian influence on Christianity is established fact settled among scholars unanimously. The most careful scholars approach the question with nuance and caution, acknowledging that some concepts may have similar appearances across traditions while insisting that the historical evidence for direct borrowing remains contested and often unclear. Many scholars distinguish between the possible influence of Zoroastrian thought on late Jewish eschatology and apocalyptic literature and the claim that all Christian doctrine derives from Zoroastrianism. Even scholars who grant some influence on the development of Jewish apocalyptic thought do not conclude that this invalidates Christian doctrine or reduces it to plagiarism from pagan sources.

The Catholic position, stated in the response from Catholic Answers, articulates this nuanced view clearly: “It is true that according to Zoroastrianism, the birth of Zoroaster was foretold long in advance and was attended by miraculous circumstances. These similarities with Christianity do not mean that Jewish Old Covenant prophecy and Christian New Covenant fulfillment borrowed from Zoroastrianism. That would erroneously imply that they were manufactured stories, myths, instead of presenting actual God-ordained realities.” This statement captures the essential Catholic response to these claims about borrowing. Even if some external parallels exist between different religions, these do not establish that Christian doctrine is borrowing or plagiarism because Christian claims rest on revelation and historical events believed to be real and actual. The Catholic Church maintains that Jesus Christ is the historical, risen Son of God and that the Church’s doctrines flow from this reality and are grounded in Scripture and apostolic tradition. Christian doctrine is not mythology meant to convey timeless truths or borrowings from foreign sources but rather the Church’s response to God’s self-revelation in Christ and Christ’s redemptive work for humanity.

The Distinction Between Terms and Theological Doctrines

A critical distinction often overlooked in plagiarism arguments concerns the difference between borrowing terms and borrowing doctrines or core theological ideas. All languages and cultures borrow words from each other, and this represents normal cultural contact and linguistic evolution rather than intellectual theft or plagiarism. The Catholic Church, like all Christian churches, reads Scripture in translation and uses terms that have traveled through various languages and cultures across centuries and millennia. The word “paradise” may have Persian origins through normal linguistic transmission, but the Christian doctrine of paradise as the eternal dwelling place of the blessed in God’s presence represents a distinct theological understanding shaped by Scripture and Christian reflection. Similarly, the term “angel” derives from Greek “angelus,” meaning messenger, a linguistic term adopted to describe spiritual beings described throughout Scripture. The fact that the word has Greek origins does not make the doctrine of angels a borrowing from Greek religion, which actually had a quite different understanding of divine and supernatural beings. When examining claims of borrowing from Zoroastrianism, it is necessary to distinguish between the language used to express doctrine and the substance of the doctrine itself.

A doctrine involves substantive claims about reality and about God’s nature and God’s action in the world and human history. When two religions arrive at similar doctrines through their own traditions and internal theological development and reflection, that represents convergence on religious truth rather than plagiarism from one source to another. If the Church had simply taken the Persian word “paradise” and adopted it along with Persian theological concepts of paradise and the afterlife, one might speak of borrowing doctrine. But the Church took a useful descriptive term and applied it to a Christian theological reality understood through Scripture and developed through centuries of Christian reflection and prayer. This represents not plagiarism but rather the natural process by which any religion adapts language and concepts to express its understanding of ultimate reality. The Catholic Church’s theological vocabulary is filled with terms borrowed from Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Aramaic, and other languages and cultures throughout the world. This linguistic borrowing reflects the Church’s engagement with the broader human culture and the reality that Christian revelation must be intelligible to human minds situated in particular cultural and linguistic contexts. The Church has never claimed that its vocabulary originates in a vacuum but rather has always been aware of linguistic sources and cultural influences in its use of language.

Authority and Tradition as the Basis of Catholic Doctrine

The Catholic Church grounds its doctrine ultimately in Scripture and Tradition as transmitted and interpreted through the living Magisterium of the Church with its authentic teaching authority. Scripture represents the written record of God’s revelation to humanity culminating in Christ, while Tradition represents the living transmission of that revelation through the Church’s teaching, prayer, practice, and witness across the centuries. Any doctrine claimed to belong to authentic Catholic teaching must be traceable to Scripture and the unbroken tradition of the Church from the apostolic period to the present day. Doctrines that appeared suddenly in one period without precedent in Scripture or earlier Church teaching would indeed raise serious questions about their authenticity and source. The major doctrines claimed to be borrowed from Zoroastrianism have never appeared in this sudden manner in Church history. Rather, each can be traced through layers of development within Scripture itself and through the testimony of early Church fathers and the decisions of ecumenical councils. The doctrine of Satan appears in Scripture clearly and is developed throughout patristic theology by the Church Fathers. The doctrine of resurrection is grounded in Scripture and defended by the early Church fathers as the proper interpretation of biblical promises and the nature of God’s plan for creation. The doctrine of the Last Judgment appears in Scripture prominently, particularly in the Gospels and in the Revelation to John, and is consistently affirmed by the Church throughout history.

The Church’s reliance on Scripture and Tradition as its ultimate sources of authority means that external cultural influences, while possible and sometimes acknowledged, do not determine what the Church teaches. The Church does not accept a doctrine simply because it appears in a neighboring religious tradition or culture, nor does it reject a doctrine because external parallels exist in other religions. Rather, the Church asks whether a doctrine is found in Scripture as the foundation, whether it is consistent with the Church’s tradition throughout history, and whether it illuminates God’s revelation in Christ for believers. By these criteria, the major doctrines attributed to Zoroastrian borrowing are affirmed as authentic expressions of Christian faith and Catholic belief. They have their deepest sources in Scripture, they are consistent with the unbroken tradition of the Church, and they serve the Church’s primary purpose of bringing the faithful to know God through Christ and to live in accordance with the Gospel. The mere existence of linguistic connections or conceptual similarities with other religious traditions does not undermine the authentic Christian character of these doctrines or reduce them to plagiarism from pagan sources. The Church maintains confidence in its doctrines because they are rooted in revelation and developed through the Holy Spirit’s guidance.

The Centrality of Christ’s Resurrection to Christian Doctrine

At the heart of the Catholic response to plagiarism claims lies the conviction that Christian revelation is unique and not reducible to the products of human religious imagination or cultural borrowing from other sources. Jesus Christ, God’s Son and Savior, became incarnate in human history, lived among people, died on the Cross, and rose from the dead on the third day. This central claim of Christianity is not a concept or idea that can be borrowed from other religions but rather a historical event that either happened in time or did not happen. The resurrection of Jesus is not a philosophical doctrine about the nature of the afterlife but a claimed historical event that the Church proclaims changed history and human destiny forever. All other Christian doctrines flow from this central reality of Christ’s resurrection and redemptive work. If Christ rose from the dead, then Satan has been conquered and evil does not have ultimate power over creation. If Christ conquered death through His resurrection, then the resurrection of the dead becomes intelligible as the extension to the faithful of Christ’s own victory over death. If God so loved the world that He sent His only Son to die and rise for humanity’s salvation, then the final judgment and the restoration of creation represent the completion of God’s loving plan for creation.

The Catholic understanding holds that while cultural parallels and conceptual similarities may exist between Christianity and other religions, the ultimate source of Christian doctrine is God’s revelation culminating in Christ. The Church does not ask whether non-Christian religions taught concepts similar to Christian doctrines or whether other religions developed similar ideas. Rather, the Church asks whether those doctrines accurately express God’s self-revelation in Christ and whether they faithfully represent the Church’s understanding of Scripture and apostolic tradition. By this standard, the doctrines attributed to Zoroastrian borrowing remain affirmed as authentic and essential elements of Christian faith. The Church teaches that God is not indifferent to human cultures and that the divine Word spoke to people in the Old Testament through the prophets, using language and concepts familiar to them in their time. The Church similarly recognizes that revelation is intelligible within cultural contexts and uses terms and categories drawn from human experience and knowledge. However, this cultural intelligibility does not reduce revelation to merely cultural product. Rather, it demonstrates that the transcendent God became incarnate and communicable in human terms while remaining fully divine and transcendent. The Incarnation itself shows how God entered human history and human culture while maintaining absolute uniqueness and transcendence as the source of all being.

The Final Refutation and Affirmation of Catholic Truth

The claim that the Catholic Church represents a wholesale plagiarism of Zoroastrian religion cannot be sustained by careful historical and theological examination of the evidence. While scholars may debate the extent to which Zoroastrian thought influenced certain developments in Jewish theology, particularly in the area of eschatology and angels, this represents a vastly different claim from the assertion that Christianity is essentially Zoroastrian religion wearing Christian clothes. The specific claims examined throughout this article, including that Christmas was adopted from Mithraism in the fifth century, that the three kings represent a distortion of Zoroastrian priests, and that fundamental doctrines like resurrection and Last Judgment were borrowed wholesale, all fail to withstand scholarly scrutiny. Christmas was already celebrated on December 25 in the fourth century, not suddenly adopted in the fifth century from a declining pagan cult. The Three Kings represent a genuine Gospel narrative with its own development in Church tradition, not a political manipulation to replace pagan religion. The doctrines of resurrection, Last Judgment, and angels can be traced through Scripture to authentically Jewish and Christian sources developing over centuries through genuine theological reflection. The Catholic Church maintains with confidence that its doctrine flows from God’s revelation in Christ as witnessed in Scripture and interpreted through the Church’s living tradition. This revelation occurred within human history and human culture, but it is not reducible to cultural product or to borrowing from other religions. The Church acknowledges linguistic borrowing and recognizes that God’s truth may appear in fragmented form in other religious traditions.

However, the Church’s primary source remains Scripture and the apostolic tradition passed down through the Church under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Doctrines that can be traced through Scripture and patristic tradition to authentic Christian sources cannot be fairly characterized as plagiarism from external sources. The challenge posed by claims of Zoroastrian influence has prompted Catholic scholars to deepen their understanding of how revelation develops within culture and how the Church’s doctrines emerge from prayerful engagement with Scripture. In meeting this challenge, the Church has found deeper confirmation of the authenticity of its faith and more profound insight into how God’s revelation became intelligible in particular human contexts while maintaining its transcendent character. Catholics can respond to these claims with intellectual honesty and scholarly rigor, acknowledging cultural contact while maintaining the conviction that Christian doctrine flows from God’s self-revelation. The Church’s confidence in its teachings rests on their foundation in Scripture and consistent testimony through the tradition. As the Church continues to articulate its faith to new generations and in new cultural contexts, it does so with the assurance that the Holy Spirit guides this living transmission of revealed truth from Christ through the apostles to the Church today.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.