Brief Overview

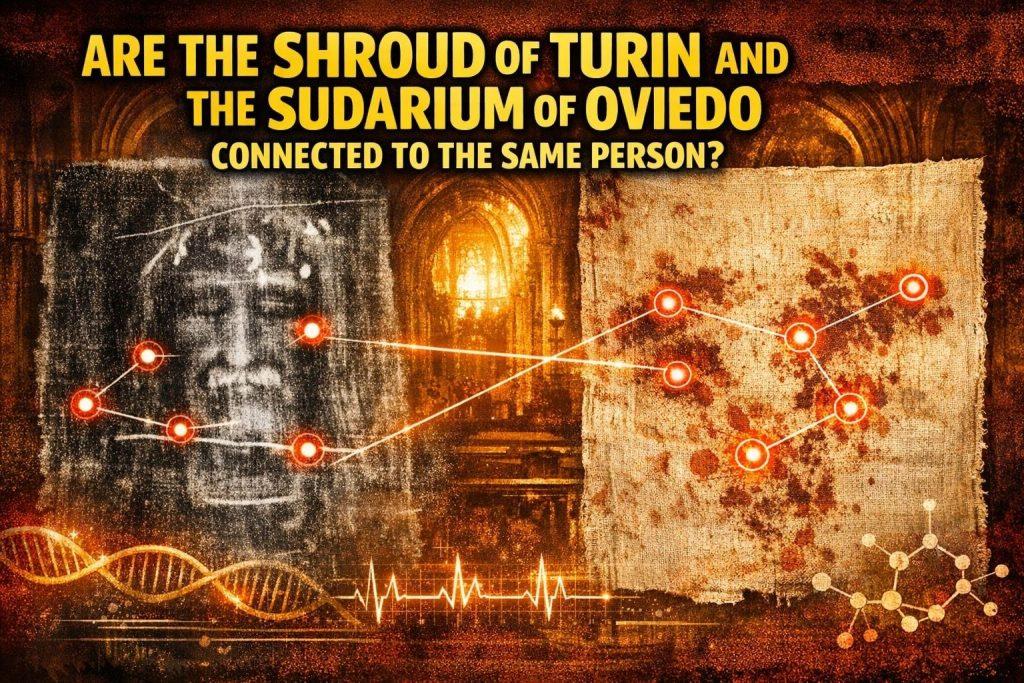

- The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth housed in Turin, Italy, that bears an image of a crucified man and is believed by many to be the burial shroud of Jesus Christ.

- The Sudarium of Oviedo is a smaller, bloodstained cloth kept in Oviedo, Spain, that is traditionally understood to have covered the face of Jesus after his death.

- Scientific research has identified more than seventy points of correlation between the two cloths, suggesting they covered the same person.

- The Sudarium has better-documented history than the Shroud, with clear records showing it was in Spain since the 7th century.

- Catholic tradition teaches that relics can inspire devotion and intercession with the saints, while God alone is the source of all grace and healing.

- Both cloths remain objects of veneration for Catholics who seek to honor the mystery of Christ’s passion and death.

The Shroud of Turin and Its Characteristics

The Shroud of Turin stands as one of the most famous relics in Christian history, generating intense scholarly discussion and genuine fascination for centuries. This burial cloth measures approximately 14 feet by 3.5 feet and is composed of linen material that shows remarkable preservation despite its age. The most striking feature of the Shroud is the image of a man displayed upon its surface; this figure appears to show clear signs of physical trauma consistent with crucifixion. The image demonstrates many anatomical details, including a bearded face, a prominent nose, and markings across the body that correspond to wounds that would result from crucifixion practices in the first century. Unlike typical images created through painting or staining, the image on the Shroud appears as a negative, resembling a photographic negative when examined under modern analysis.

The Shroud of Turin gained widespread attention during the medieval period and has been subjected to intense scientific scrutiny throughout the modern era. The cloth displays bloodstains in locations that align precisely with what would occur during a crucifixion, particularly around the head, hands, and feet. Researchers have noted that the blood appears to have been applied to the cloth before the formation of the body image, suggesting the cloth came into contact with a body in a specific manner. The Shroud also exhibits traces of pollen that would be consistent with the Jerusalem region, and chemical analysis has revealed the presence of myrrh and aloes, substances mentioned in scripture as part of Jewish burial practices. The lack of decomposition marks on the Shroud has led many researchers to conclude that the body it covered remained in contact with the cloth for only a limited period of time, consistent with the gospel accounts of Jesus’ resurrection.

The Sudarium of Oviedo and Its History

The Sudarium of Oviedo is a second relic of significant importance to the Christian faith, though it receives less public attention than the Shroud of Turin. This cloth measures approximately 33 inches by 21 inches and consists of linen material that shows signs of age and careful preservation. Unlike the Shroud, the Sudarium displays no discernible image to the naked eye; instead, it bears numerous bloodstains and fluid marks that tell their own important story about the person it covered. The stains on the Sudarium show remarkable symmetry and distribution patterns that suggest the cloth was folded in a specific manner when applied to a face. The cloth itself possesses no artistic or monetary value, which supports the understanding that it was preserved because of its genuine connection to the events of the Christian faith rather than for commercial reasons.

The documented history of the Sudarium extends back further than many historical records of the Shroud, making it an important witness to Christian tradition. According to records preserved from the medieval period, the Sudarium was in Palestine until the year 614, when the Persian king Chosroes II invaded the Byzantine provinces. The cloth was spirited away to safety through northern Africa by Philip the Presbyter, a leader of the Christian community in Palestine. The Sudarium was taken first to Alexandria in Egypt, then traveled across the northern coast of Africa to Spain, specifically arriving at Cartagena. From Spain, the cloth moved to Seville under the care of bishops and church leaders, then to Toledo in central Spain. When the Moors invaded the Iberian peninsula in 711, the precious relic was moved northward to avoid destruction, eventually reaching the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo, where it has remained since approximately 842 AD. In 1075, the chest containing the Sudarium was officially opened in the presence of King Alfonso VI, establishing official recognition of the relic by secular authorities.

Understanding First-Century Jewish Burial Practices

To fully comprehend the significance of both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo, one must understand the burial customs practiced by Jewish people in first-century Palestine. Jewish burial tradition required multiple cloths and specific rituals to prepare the deceased for burial with proper respect and honor. The gospel accounts in John 20:6-7 specifically mention both “linen wrappings” and a separate “face cloth” that was “rolled up in a place by itself,” indicating that different cloths served different purposes during burial. The face cloth was placed on the head of the deceased and remained there during the period before final entombment. This practice served both practical and spiritual purposes; it expressed compassion for the deceased and their family while also maintaining dignity and respect for the body. The placement of myrrh and aloes on burial cloths was a standard practice that would preserve the body and honor the deceased. When the Sudarium is studied carefully, forensic analysis reveals traces of these very substances, precisely as described in the gospel accounts of Jesus’ burial.

Jewish burial practice also dictated that if the face of the deceased showed signs of injury or disfigurement, the face cloth would be particularly important to maintain the dignity of the person in death. The gospels report that Jesus underwent brutal torture during his crucifixion, including the crown of thorns placed upon his head. The face of a crucified criminal would certainly have been disfigured, making the placement of a respectful face cloth a crucial part of honoring Jesus’ body in death. This practice would explain why John’s gospel specifically mentions the face cloth as a separate item from the burial shroud. The Sudarium’s presence at the crucifixion site, as suggested by tradition and forensic evidence, would place it exactly where gospel accounts indicate such a cloth would have been used. Understanding these cultural practices allows modern readers to appreciate why two separate cloths would have been part of Jesus’ burial and why both relics would be preserved as precious witnesses to the events described in scripture.

Forensic Evidence Connecting the Two Cloths

Modern scientific analysis has revealed remarkable correlations between the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo, providing compelling evidence that both cloths came into contact with the same person. Research conducted by experts from the Spanish Center for Sindonology, including work by Dr. Juan Manuel Miñarro from the University of Seville, has identified more than twenty points of correlation between the two cloths using forensic and geometric analysis. These correlations exceed the minimum threshold required by most judicial systems worldwide to identify a person, which typically requires between eight and twelve significant points of matching evidence. The frontal side of the Sudarium shows approximately seventy points of correspondence with the image on the Shroud, while the rear side displays roughly fifty points of correlation, suggesting extraordinary precision in the matching of features.

The bloodstains present on both cloths provide particularly compelling evidence of connection. Researchers have determined that the blood type on both the Shroud and the Sudarium is AB, which is a relatively uncommon blood type today and was likewise uncommon in first-century Palestine. More significantly, the specific location of bloodstains matches between the two cloths with remarkable accuracy. When the Sudarium’s stain patterns are compared with the facial image visible on the Shroud, the stains correspond precisely to features such as the beard, the nose, and the facial structure of the man depicted on the Shroud. The distribution of blood indicates fluid flows from a body that experienced crucifixion-related trauma, with particular concentration in areas where crucifixion victims would bleed. The nose length measured on both cloths is approximately eight centimeters, and the thorn stains visible on the nape of the neck on the Sudarium align perfectly with similar markings on the Shroud. These correlations would be virtually impossible to occur by random chance if the two cloths had covered different individuals.

The Timeline and Sequence of Events Suggested by the Cloths

The forensic analysis of both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo provides insight into the sequence of events that occurred at the time of the person’s crucifixion and burial. Evidence from the Sudarium suggests that this cloth was placed on the face of the deceased while the body remained in an upright position, consistent with the person hanging on a cross. The staining pattern indicates that the man covered by the Sudarium was bleeding from pulmonary edema through the mouth and nose, a condition that occurs when fluid accumulates in the lungs during crucifixion. After a period of time, the forensic evidence suggests the body was laid face down, indicating removal from the cross. The cloth was then adjusted slightly and remained in place for approximately one hour after the body was laid down. According to the traditional account and forensic interpretation, the Sudarium was removed from the face and set aside before the body was wrapped in the larger Shroud for burial.

The Shroud of Turin then covered the entire body of the deceased after it was laid in the tomb in a supine position. The image on the Shroud shows the man lying on his back, with the cloth wrapped around the body in the manner described by gospel accounts and consistent with Jewish burial practices. The Sudarium would have been removed prior to this final wrapping, which explains why John’s gospel mentions the face cloth being “rolled up in a place by itself,” separate from the other burial wrappings. The bloodstain correlations between the two cloths and their anatomical correspondence suggest that the same body experienced contact with both cloths in the sequence described by traditional Christian accounts. The chemical analysis of both cloths reveals traces of limestone dust consistent with soils found in Jerusalem, particularly in the region near Calvary where crucifixions took place. The presence of myrrh and aloes residues on both cloths aligns with the gospel description of burial preparations conducted by Joseph of Arimathea and other followers of Jesus.

Chemical and Microanalytical Findings

Modern chemical analysis techniques have provided additional evidence supporting the connection between the two cloths. X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted on the Sudarium revealed significant concentrations of calcium in the areas bearing bloodstains, which correlates with calcium deposits similarly found in concentrated areas on the Shroud. The calcium is particularly concentrated near the tip of the nose on both cloths, which is anatomically unusual but would make sense if both cloths came into contact with the same body that had experienced trauma in this region. The presence of calcium in these specific areas is consistent with dust and soil particles that would adhere to physiological fluids while still fresh, suggesting that the calcium deposits were transferred to both cloths at approximately the same time, when the body was in contact with Jerusalem soil near the crucifixion site. The concentration of strontium, another chemical element examined in the analysis, also matches the type of limestone characteristic of the rock formations near Calvary in Jerusalem.

Pollen analysis has revealed traces of pollen species consistent with vegetation found in the Jerusalem area on both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo. The presence of identical pollen species on both cloths further supports the understanding that both fabrics were exposed to the same geographic location during their history. The pollen grains are distinctive and would not naturally occur in Europe, making their presence on both cloths particularly significant. Microscopic examination of both cloths has revealed red blood cells, serum, and other biological materials consistent with traumatic bleeding from a crucified person. The presence of myrrh and aloes residues, confirmed through chemical analysis, matches the gospel account in John 19:39-40 describing how Nicodemus brought myrrh and aloes to anoint Jesus’ body. The combination of all these chemical and microanalytical findings creates a compelling scientific case that the two cloths came into contact with the same body, experienced similar environmental conditions, and were subjected to similar burial preparation practices consistent with first-century Palestinian Jewish customs.

The Challenges to Historical Authentication

While the scientific evidence connecting the two cloths is compelling, historians and scholars note various challenges in definitively establishing the authenticity of either relic as belonging specifically to Jesus Christ. The Shroud of Turin underwent radiocarbon dating analysis in 1988, which suggested a date in the 1300s for the cloth’s origin, considerably later than the time of Jesus. This controversial result has led some scholars to question whether the Shroud is genuinely ancient or represents a medieval creation. However, critics of this dating have noted that contamination from later handling, oil residue accumulation over centuries, or other factors could have affected the accuracy of the radiocarbon analysis. The scientific community remains divided on the reliability of the 1988 dating results, with some researchers arguing that the methodology was flawed or that contamination factors were not adequately addressed.

The Sudarium of Oviedo also underwent radiocarbon dating and was assigned a date of approximately 700 AD, which is notably later than the first century but still earlier than the Shroud’s controversial dating. Scholars have suggested that later oil contamination from its preservation in the Arca Santa, the elaborate reliquary chest in which it has been housed in Spain, could have affected the accuracy of this dating as well. The documented history of the Sudarium beginning in the 7th century does not contradict an earlier origin; rather, it provides the earliest verified historical record of the cloth’s location. The historical accounts preserved by medieval bishops, while generally reliable regarding the cloth’s presence in Spain, were recorded more than six centuries after the events they describe and thus cannot be verified through direct documentation. Scholarly caution regarding authentication is appropriate and reflects the rigorous standards that historical and scientific disciplines apply to claims about ancient artifacts. Nevertheless, the correlation between the physical evidence on both cloths and the biblical accounts of Jesus’ burial remains remarkably consistent.

The Role of Faith in Understanding the Relics

The Catholic Church teaches that belief in the authenticity of specific relics is not a matter of faith that is mandatory for salvation or essential Christian practice. The Catechism of the Catholic Church addresses the veneration of relics and emphasizes that relics serve as aids to devotion and sources of inspiration rather than objects of worship themselves (CCC 1674). For Catholics, relics represent tangible connections to the mysteries of faith and can inspire prayer, contemplation, and deepening of spiritual commitment. The Church encourages veneration of relics as a practice that honors the lives of saints and martyrs, but the Church does not require belief in the authenticity of any particular relic. Catholics are free to study the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo with genuine scholarly interest while neither claiming certain knowledge of their authenticity nor dismissing them as definitely fraudulent.

The relationship between reason and faith becomes relevant when considering these relics. Scientific evidence can provide insights into the age, composition, and history of material objects, but science cannot definitively prove or disprove spiritual truths. If the Sudarium of Oviedo and the Shroud of Turin are genuine burial cloths of Jesus Christ, then they represent physical evidence of the reality of Jesus’ crucifixion and death. However, they do not prove the resurrection; the resurrection is understood as a spiritual reality that transcends material examination. The empty tomb and the risen appearances of Jesus are matters recorded in scripture and attested to by the faith of the early church, but they are not scientific questions that can be resolved through laboratory analysis. Catholics are invited to approach these relics with reverence and openness to what they might teach about Jesus’ suffering and death, while recognizing that ultimate faith in Christ must rest on spiritual foundations rather than material evidence alone.

Spiritual Significance of the Sudarium of Oviedo

The Sudarium of Oviedo holds particular spiritual significance as a potential witness to the dignity Christ maintained even in death. If the Sudarium is genuinely the cloth that covered Jesus’ face after his crucifixion, then it represents the moment of profound respect shown to him at a time when his body bore the marks of brutal torture. The gospel account in John 20:6-7 describes the careful placement and subsequent removal of this face cloth, treating it as a distinct and important element of the burial narrative. Jewish cultural practice required that the faces of disfigured deceased persons be respectfully covered, and if Jesus’ face showed the marks of the crown of thorns and other crucifixion trauma, this covering would have been an act of compassion by his followers. The Sudarium thus represents not just a physical artifact but a spiritual testimony to the humanity of Jesus, his suffering, and the loving care with which his followers treated his body even after his death.

The Sudarium also provides unique evidence because of its simplicity and lack of artistic value. Unlike relics that acquired fame and wealth through religious or political significance, the Sudarium is a modest cloth with no intrinsic value other than its historical association. The fact that this plain cloth was preserved so carefully and its history documented so thoroughly suggests that those who maintained it did so because they genuinely believed in its historical importance and spiritual significance. There would be no financial incentive to preserve such a cloth, no artistic reason to maintain it, and no political advantage to safeguarding it through centuries of danger. This practical consideration lends credibility to the claim that the cloth was preserved because it actually embodied the spiritual importance attached to it by faithful Christians who understood themselves to be guardians of a sacred relic. The care taken to protect it during the Persian invasion, the Moorish conquest of Spain, and throughout subsequent centuries suggests a conviction about its authenticity that informed decisions about risking lives to preserve it.

The Catholic Practice of Relic Veneration

The Catholic Church has maintained the practice of venerating relics since the earliest centuries of Christian history, with evidence of this practice appearing in accounts from the time of the apostles themselves. The Church teaches that veneration of relics is distinct from worship, which is offered to God alone (CCC 828). When Catholics venerate a relic, they honor the saint or person associated with the relic as a way of honoring God and seeking the intercession of those who lived holy lives. Scripture provides multiple examples of God working miracles and healings through contact with relics of holy people, including accounts in 2 Kings 13:20-21 describing a man who came back to life when his body touched the bones of the prophet Elisha, and Acts 5:12-15 describing crowds gathering to be healed by Peter’s shadow. These biblical accounts establish that God chooses to work through physical objects and demonstrates his power in tangible ways accessible to human experience and understanding.

The Council of Trent provided authoritative teaching on relic veneration, affirming that the bodies of saints and martyrs, which were “living members of Christ” and “temples of the Holy Spirit” during their earthly lives, continue to merit reverence and honor after death. The Church teaches that through relics, God bestows many benefits on the faithful, not because the relics themselves possess magical power, but because God chooses to act through them and to draw believers’ attention to the saints as models and intercessors (CCC 828). When Catholics venerate a relic, they may touch or kiss the reliquary that houses it, kneel in prayer before it, or simply stand in prayerful contemplation while asking the saint to intercede with God for specific intentions. The proper attitude in relic veneration is one of reverence and spiritual devotion rather than superstitious expectation that the physical object itself will automatically produce results. Grace and healing come from God alone, but the Church affirms that God may choose to work miracles through the relics of saints as a sign of honor and as an encouragement to faith.

Understanding Relic Classification and Church Approval

The Catholic Church classifies relics into three categories based on their relationship to the saint or holy person they represent. First-class relics are fragments of the body of a saint or, in the case of Christ, items directly connected to his body such as the burial cloths. Second-class relics are objects that personally belonged to a saint, such as clothing, prayer cards, or items the saint used regularly. Third-class relics are objects that have been touched to a first or second-class relic and thus have a secondary connection to the saint. The Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo, if authenticated as burial cloths of Jesus Christ, would be considered first-class relics because of their direct physical contact with Christ’s body. However, Christ’s relics occupy a unique position in the Church’s understanding; while other first-class relics are venerated as aids to devotion and intercessory prayer, Christ’s relics are recognized as connected to the source of salvation itself.

The Church requires that relics be subjected to careful examination and verification before they are officially recognized and approved for public veneration. Bishops have the responsibility to verify relics and ensure that claims of authenticity are supported by evidence and scholarly investigation. The Church prohibits the sale of first and second-class relics; they can only be transferred by gift, and significant relics may not be transferred without Vatican permission. The Church has established these safeguards to prevent fraud and to maintain respect for relics as spiritual treasures rather than commercial commodities. For centuries, the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo have been venerated by Catholics and pilgrims, with increasing scholarly research conducted to examine and understand their properties. The Church does not require belief in the authenticity of these relics but recognizes that they inspire genuine devotion, encourage prayer, and deepen faith in Christ’s passion and resurrection for those who encounter them with reverence.

The Relationship Between Material Evidence and Spiritual Truth

The connection between the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo suggests important theological reflections about the relationship between material creation and spiritual reality. Christianity affirms that God created the physical world and that matter itself is not inherently opposed to spirit; rather, the two coexist in God’s creation. Jesus himself is understood as the incarnation of God in physical form, and Christian faith maintains that the body is destined for resurrection and eternal life alongside the soul. If these two cloths genuinely bear the marks of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial, they testify to the physical reality of Christ’s incarnation and the importance of embodied existence in Christian theology. The material traces left on the cloths would represent tangible evidence that Jesus truly suffered, truly died, and truly possessed a real body that could be touched and handled by his followers.

The scientific correlations between the two cloths provide a form of material evidence that supports the gospel accounts of Jesus’ burial, but they do not constitute proof of the resurrection or of Jesus’ divinity. These matters remain objects of faith and spiritual conviction rather than scientific demonstration. However, the reliability of the material evidence regarding the burial events supports confidence in the gospel narratives as historically grounded accounts. If the gospel writers were accurate in their descriptions of specific burial practices, specific individuals involved in the burial, and specific details about burial cloths, then their testimony about other matters is strengthened. This does not mean that faith depends on scientific confirmation, but rather that the consistency between material evidence and scriptural accounts provides reassurance that the gospels preserve genuine historical memory of the events they describe. For Catholics and other Christians, the relics serve as reminders of the incarnational character of Christian faith, which affirms that God became flesh and that spiritual reality intersects constantly with material creation.

Implications for Understanding the Resurrection

Both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo relate to the events surrounding Jesus’ death and burial, but they also point toward the mystery of the resurrection. If these cloths are genuine, they testify to the reality of Jesus’ death and the proper handling of his body in burial. However, the gospel accounts make clear that the Shroud was left behind in the tomb when Jesus rose from the dead, suggesting that his risen body was not constrained by the physical cloth in which it had been wrapped. The gospels indicate that Jesus’ risen body possessed properties that differed from his earthly body; the risen Jesus could appear and disappear, could enter locked rooms, yet could also be touched and could eat food. The cloths left behind are thus connected not to the resurrection body but to the pre-resurrection human life and death of Jesus. Understanding the relics in this way maintains the distinction between the earthly Jesus who died and was buried and the risen Jesus whose resurrection transcended the limitations of his previous earthly existence.

The preservation of the burial cloths across centuries serves as a tangible reminder of the incarnational events of Christ’s passion, death, and burial. While the relics do not directly provide evidence of the resurrection, they strengthen faith in the historical reality of the events that preceded it. For believers, knowing that Jesus truly died, truly was buried with respect according to his followers’ understanding, and truly left behind these material witnesses to those events, provides a foundation for faith in his resurrection. The resurrection would be a hollow theological abstraction if Jesus had never truly lived in a real body, never truly suffered and died, never truly been buried. The relics remind believers that the Christian gospel is rooted in historical events involving a real person with a real body who experienced real suffering. This foundation of historical reality makes the proclamation of the resurrection meaningful within Christian theology and practice.

The Contemporary Witness of the Relics

In the modern era, both the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo continue to draw researchers, pilgrims, and believers who seek to understand their significance and authenticity. The Shroud is displayed occasionally in Turin at the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, where crowds gather to view and venerate this remarkable cloth. The Sudarium is displayed three times yearly in Oviedo on Good Friday, the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross, and its octave, allowing the faithful to encounter this relic in a liturgical context. Scientific research continues on both cloths, with researchers employing increasingly sophisticated analytical techniques to examine the cloths’ composition, the properties of the bloodstains, and the traces of materials adhering to the fabric. This ongoing scholarly attention maintains public awareness of the relics and demonstrates that serious investigation into their authenticity proceeds according to rigorous academic standards.

For many contemporary Catholics, encountering the Shroud or Sudarium in person or viewing high-quality images of the cloths provides a moment of profound spiritual connection to the mystery of Christ’s passion and death. The material reality of the cloth, visible and tangible, makes the ancient events of the gospels feel immediate and real in a way that purely spiritual contemplation might not achieve. Looking at the image on the Shroud or observing the bloodstains on the Sudarium can prompt reflection on the suffering Jesus endured, the care shown to his body by his followers, and the significance of his death for human salvation. Pilgrims and visitors frequently report that encountering these relics strengthens their faith and inspires deeper commitment to living as Christians. Whether or not one is convinced of the relics’ authenticity, the experience of encountering an ancient cloth that might have covered Jesus’ body provokes genuine spiritual reflection and emotional response that can deepen faith commitment.

Conclusion: Two Cloths, One Story, One Mystery

The comparison between the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo reveals two relics that bear remarkable correlations in their physical properties, bloodstain patterns, and anatomical features. Scientific research has demonstrated correlations exceeding the standards required by legal systems to identify individuals, suggesting with high probability that both cloths came into contact with the same person. The Sudarium’s well-documented history in Spain provides a clear record of its preservation back to the medieval period, while the Shroud’s more mysterious history has attracted both scholarly investigation and popular interest. If these two relics are authentic burial cloths of Jesus Christ, they provide material testimony to the reality of his crucifixion, his death, and his burial according to Jewish customs by his devoted followers. The relics do not prove the resurrection or provide scientific demonstration of Jesus’ divinity, but they do ground Christian faith in historical events and physical reality.

For Catholics and other Christians, the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo serve important spiritual functions as aids to devotion and sources of inspiration. The Church permits and encourages veneration of these relics while maintaining that belief in their authenticity is not required for salvation or essential faith practice. The ongoing research into these cloths proceeds according to scientific principles and scholarly standards, and legitimate differences of opinion about authenticity remain among serious scholars and believers. What these relics ultimately offer to the faithful is an invitation to deeper meditation on Christ’s suffering and death, to gratitude for the salvation won through his passion, and to commitment to living according to the gospel message. The cloths themselves, whether definitively authenticated or not, direct attention beyond themselves to the person they are believed to have covered. In this way, the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo continue to serve their essential purpose as relics that draw human hearts toward the mystery of Christ and invite all people to encounter the love of God expressed through Christ’s life, death, and resurrection.

Disclaimer: This article presents Catholic teaching for educational purposes. For official Church teaching, consult the Catechism and magisterial documents. For personal spiritual guidance, consult your parish priest or spiritual director. Questions? Contact editor@catholicshare.com

Sign up for our Exclusive Newsletter

- 📌 Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- 🎁 Join us on Patreon for Premium Content

- 🎧 Check Out These Catholic Audiobooks

- 📿 Get Your FREE Rosary Book

- 📱 Follow Us on Flipboard

-

Recommended Catholic Books

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books — invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for your support.